The Celilo Wy'am Are Still Here

Matriarch Lana Jack continues a decades-long fight for federal recognition of her band—and the right to continue living on the lands of her ancestors.

Lana Jack performing a dance in honor of her ancestors, The Dalles, Oregon, February 26, 2021

Josué Rivas for NRDC

Lana Jack speaks slowly and intentionally, the pauses between her words and her sentences inviting the listener to share in her grief and in her strength. She brings you into that space cautiously—a history of intergenerational trauma necessitates earning her trust—but also urgently. For Jack, one of the last remaining Celilo Wy’am, a federally unrecognized tribe on Oregon’s Mid-Columbia River, sharing the history of her people and their persecution is a painful but necessary part of survival.

As with most cultural histories, certain events are so significant that time is marked as coming either before it or after it. For the Celilo Wy’am, that day is March 10, 1957, when the floodgates closed for the first time on the newly constructed The Dalles Dam, silencing Celilo Falls after just a few hours. The obtrusive 1,380-foot, steel-and-concrete structure brought down the ancient waterfall’s abundant fishery—and with it crumbled a way of life for Indigenous People all along the Columbia River.

“It seemed unfathomable that something like this could happen, that Celilo Falls could disappear,” Jack says. “And that we could be made as a people to perish.”

Jack, who was born nine years after the dam went up, says that her mothers—her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother—dressed in black and wept in mourning that day. “My mothers cried and cried with great sorrow. With no justice in sight, with no hope. When they were crying, they knew that the salmon were all going to die,” she says. They were right: Where millions of wild salmon once returned—so many, Jack says, that people could smell them coming back—today, only a small number do.

“And, somehow, I was there at the flooding of the falls, even though I wasn't even born yet,” she continues. “I can go back to that place in time and remember how our people, how my mothers, cried in travail. Because what you do to the river, you do to the salmon. And what you do to the salmon, you do to us.”

A U.S. government property at the entrance of the Lone Pine fishing site in The Dalles, Oregon, February 26, 2021

Josué Rivas for NRDC

A Home Forever Changed

The construction of The Dalles Dam came after a century’s worth of industrialization efforts by white colonizers in the area, who were intent on capitalizing on the Columbia River’s vast resources, regardless of the ecological or human cost. “The Columbia River tribes had a sophisticated system of who could fish where and when, and that all got upended once white settlers came and started putting in fish wheels and big canneries,” explains Giulia Good Stefani, an Oregon-based attorney at NRDC. “They started commodifying fish and exporting them, and they disrupted an ancient and sacred sustainable fishery.”

What’s more, she adds, “the imposition of white [patriarchal] culture and its ways of dealing diminished the power the women had in the tribal community. All of a sudden, negotiations were primarily between men.”

Jack speaks passionately about the indispensable role of the women who came before her in ensuring their tribe’s survival. Leading up to the dam’s construction, a series of settlement discussions took place between the federal government and various Columbia River tribes, including the Yakama Nation, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, and “such other Columbia River Indians,” as the Bureau of Indian Affairs referred to federally unrecognized tribes like the Celilo Wy’am.

In contrast to tribes recognized by the U.S. government, those without this legal status are denied a government-to-government relationship with the United States and are ineligible to receive certain grants, protections, and services from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. They also generally lack the legal authority to step in when a local environment or cultural area is threatened by development. Federally recognized tribes with treaties are also eligible for certain benefits, like access to education and the Indian Health Service, and they can have the right to comanage, with federal and state agencies, natural resources like salmon. “The Bureau of Indian Affairs was tasked to protect us,” Jack says, but adds it has not always lived up to that mission—even recognized tribes haven’t always received the benefits promised to them, she says. “We, as Columbia River Indians whose parents were forced to take enrollment to benefit from said promises, stand our ground waiting for the honor of those treaty provisions, services, and protection.”

There are 574 federally recognized tribes and the U.S. Government Accountability Office estimates another 400 unrecognized tribes (not counting those in Alaska and Hawai’i, due to unique circumstances in those states).

“People have heard about the genocidal wars, forced removals, and boarding schools,” says Good Stefani. “But in lots of ways, what we have done to Native American people with the law is just as violent as what we have done on the land—and it’s still happening. Tribes like the Celilo Wy’am continue to fight just to be acknowledged,” she explains.

The Dalles Dam settlement talks led to the setting aside of a meager 7.4 acres for Native Americans beside what was Celilo Falls. Jack’s great-grandmother, Minnie Wesley Showaway, was able to secure an individual allotment in what is now Celilo Village. She did so, Jack explains, in the face of overt sexism that prioritized her husband’s voice—and signature. In 1983, Jack inherited the property from her granduncle, Moses Showaway, and today carries on her foremothers’ legacy of fighting for the right to live there and to uphold the covenant between her people, the salmon, and the river.

“In her mind and in her heart, there was something about the fight that told her: They're never going to acknowledge us as a tribe,” Jack says of her great-grandmother, who had the forethought to secure her stay as an individual aboriginal title holder, a designation Jack says Celilo Wy’am Chief Tommy Thompson negotiated in the 1940s, when he refused to make a deal around the fisheries with the U.S. government.

Even for those who did secure treaties and thereby gain government-to-government privileges that included limited funding and better access to health care and education on their reservations—life was not easy. But, says Good Stefani, “the tribes who refused to sign any of those documents lost the most.” What they kept is a connection to this place that is unbreakable, she adds. “They refused to be removed from the river.”

Jack showing archival images of her homelands of Celilo Falls before The Dalles Dam was constructed

Josué Rivas for NRDC

Jack inherited that determination from her ancestors. “We are the Celilo Wy’am, and we are still here,” says Jack, whose granduncle Moses gave her the name Huy-ux-pul (Ever-Present Cooling Mist at the Falls) at age seven. Wherever life took her, Moses told her, she’d have to return to Celilo, because her name was from there and connected her to the land.

Jack took the directive to heart—even though, as a “such other Columbia River Indian,” she has been denied rights to fish, gather, and hunt, as others living in Celilo Village who belong to a tribe with treaty rights may do. “I can't even go out there and catch a salmon, no matter how hungry I am, without fearing going to jail, which my sister and brother both have,” she says.

She returned to Celilo but alone, her family scattered, unable to escape the widespread dismantling many experienced as a result of colonizing efforts. “My family is now left to wander, being institutionalized or assimilated into a culture that we don't belong to,” she says. “I am alone here fighting a battle for us all.”

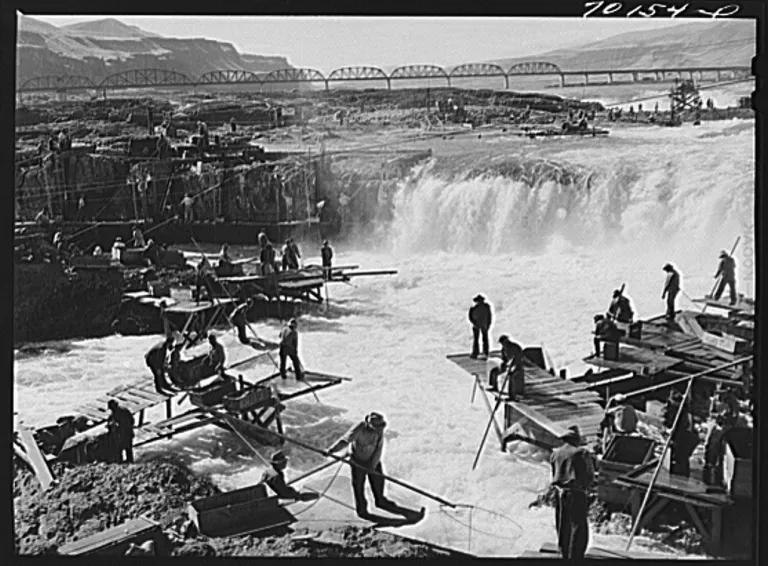

Native tribes fishing for salmon at Celilo Falls, 1941

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Over the years, the surrounding area has seen the construction of the BNSF railroad, the Celilo Canal, Interstate 84, and other industrialization. As a result, the village—which is now a cluster of 14 individual houses centered around the longhouse—has been relocated a total of six times. The Celilo Wy’am burial grounds, for which Jack is a gatekeeper, have shifted too—the original site submerged by The Dalles Dam. During the last relocation, as Jack faced eviction, she reluctantly agreed to a settlement that the government deemed the “fulfillment of a promise.” The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the new houses in 2008 to replace those it razed for development but left the people there with faulty wiring and sagging walls, overlooking a forever-changed river landscape.

“But it’s about more than just housing,” Jack says, noting that the house she lives in is not a home. “It’s health care, it’s education. It’s keeping our sacred sites, our rituals. It’s keeping the natural law. We’ve been denied all of that based on their so-called ‘fulfillment of a promise’ here.”

Jack delivering mutual aid to the Lylo Point fishing community along the Columbia River in Lylo, Washington

Josué Rivas for NRDC

The Fight Continues

Despite it all, with few resources and amid a global pandemic that’s hitting Indigenous communities disproportionately hard, Jack has stepped up her work as a caretaker for several fishing villages along the Mid-Columbia River. These communities face a compounded impact from COVID-19: a drastic reduction in their customer base—mainly wholesalers, who in turn sell the fish to restaurants and tourists—as well as increased risk from crowded living conditions and a lack of basic infrastructure.

The communities are located on small parcels of land along the Columbia River, all that was offered to the residents “in lieu” of the many Native American villages and fishing sites destroyed as a result of the construction of Bonneville Dam and The Dalles Dam. At some of the “in lieu” villages, Jack says, up to 50 people share a bathroom, so if one person gets sick, everyone is at risk. Electric power and running water are scarce.

As the pandemic worsened, Jack sprang into action, raising funds to deliver masks and hand sanitizer to Lone Pine, Lyle Point, and the other villages along the river, a continuation of a mobile food and clothing bank she began about eight years ago as part of the Columbia River Indian Center. A German shepherd named Hey-Hey accompanies Jack as she drives between the villages, her car packed with propane heaters, groceries, and dog food. At each stop, she speaks to the residents about COVID-19 and the other threats they face.

“My heart is for the people, and it breaks to see the extreme poverty, to see people just struggling to get by all the time,” she says. “This, too, is a continuation of the genocide. All of it goes right back to broken promises that were made to a people.”

With the new presidential administration—and the potential for the first-ever Native American secretary of the U.S. Department of the Interior in Deb Haaland—Jack sees a fresh opportunity to finally gain recognition for the Celilo Wy’am (and, she hopes, other tribes who also lack it). After years of attempts to make her case through regional offices of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, it’s become clear to her that the decision-making authority lies in Washington, D.C. Haaland, who has a personal understanding of the deep connection to ancestral lands, would be in a position to review Jack’s many legal documents. “There could finally be some justice for us,” says Jack, who, at 55, has already lived longer than most of her ancestors did. Critically, federal recognition could lead to a reunification of her family, she says, something she yearns for daily. “I feel like I'm making this last stand and pleading to a nation.”

She adds, “I continue to believe that one day the truth is going to matter to somebody. It’s going to speak to somebody who will say enough is enough. Let’s honor them instead of them just being everybody's something else.”

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Water Is Life—from Standing Rock to Oaxaca’s Mixtecan Highlands

From Dams to DAPL, the Army Corps’ Culture of Disdain for Indigenous Communities Must End

A Trailblazer for Tribal Sovereignty