Committing to Healthy, Affordable & Carbon-Free Homes in Colorado

Our homes, workplaces, and other buildings are often the foundations of our sense of comfort and community—they are also foundational to climate action.

This is the second in a series of blogs unpacking and diving deeper into aspects of the report, "Committing to Climate Action: Equitable Pathways for Meeting Colorado’s Climate Goals."

Written in collaboration with Deya Zavala of Mile High Connects and Katie McKenna of Enterprise Community Partners (MHC steering Committee Member).

Our homes, workplaces, and other buildings are often the foundations of our sense of comfort and community—they are also foundational to climate action. A recent analysis from GridLab, NRDC, and Sierra Club illustrates the extent to which Colorado must phase down carbon emissions from homes and other buildings in order to meet its climate goals. At the same time, it’s critical we expand our focus beyond simply reduced emissions. Colorado policymakers must embrace equitable, transformative housing and building policies in order to appropriately respond to and prepare for the increasing unaffordability, displacement, and health impacts of the climate crisis.

Colorado leaders should take advantage of a transitioning building sector to invest in healthier infrastructure for the state and help all Coloradans fully transition to a clean energy economy. For many, buildings are the closest relationship we have with our energy use and climate impacts. Buildings are the main sources of our energy expenses and the structures we depend on to keep us safe during climate-intensified heat waves, cold snaps, storms, and pollution. Buildings have also been a wealth generation tool at the heart of racial and economic inequity in this country. Efficient all-electric buildings are a proven, least-cost tool for eliminating carbon emissions from buildings, but they are only as effective to the extent we can make them accessible. If low-income communities and communities of color are unable to afford them, we will not reach our climate goals and we will leave those communities to pay for the aging gas infrastructure left behind. Policymakers have an opportunity to build sector policy that gets at the interlocking crises facing Coloradans which will be key to achieving sustained progress against climate change for all.

Colorado Context

Direct fuel use in buildings is responsible for 10 percent of Colorado’s climate-warming carbon emissions, and electricity use for buildings is responsible for another 16 percent. Much of that carbon comes from burning fossil gas (otherwise known as natural gas) inside our homes for water heating, space conditioning, and cooking. Carbon emissions and other pollutants from burning fossil gas in buildings are harming our planet and our families.

In order to get on the path to cleaner, healthier buildings that support the state’s climate goals, Colorado must transition away from building, homes, and businesses that depend on fossil fuels as soon as possible and prioritize climate-friendly renovations for buildings in low-income, historically under-resourced, and Black and Brown communities.

What Our Modeling Tells Us We Have to Do

As part of our report, Evolved Energy Research and Physicians, Scientists, and Engineers for Healthy Energy modeled and analyzed pathways for Colorado to meet its climate goals. Our analysis showed the stark contrast between a business-as-usual “Reference” scenario and one in which state policymakers ensure we meet our climate targets—the “Core” decarbonization scenario. We found that, absent new policy, pollution from buildings is likely to grow in Colorado and be unequally distributed. The state must act quickly to reverse this trend.

The report lays out three major strategies to cut pollution from Colorado’s buildings fast enough to meet the climate goals:

- Accelerate adoption of efficient, electric appliances in homes and offices;

- Ensure new buildings are highly efficient and fully electric as soon as possible; and

- Upgrade existing buildings to make them more efficient.

As part of these three strategies, the state must ensure that low-income households, rural communities, and renters reap the affordability, health, and comfort benefits of energy efficiency and electrification.

Efficient Electrification

Confronting the climate crisis requires a transformation of the building energy use from fossil gas to clean electricity. Highly efficient, electric options are available for heating and cooking appliances, which currently rely heavily on fossil gas, but adoption of these electric options is not expected to accelerate at the pace required to meet the climate goals without new policy.

Our modeling found that efficient, electric appliances must make up half of new space and water heaters in residential buildings and a third of new heaters in commercial buildings by 2030—up from a little over 20 percent of residential heater sales and less than 10 percent of commercial sales today. And that’s assuming almost complete decarbonization of the power sector by 2030. If the state continues to burn coal or a sizable amount of gas for electricity in 2030, then buildings will have to electrify even more quickly to help make up the emissions difference, with electric heaters making up 90 percent of sales in residential buildings by the end of this decade.

The study also found that buildings are a major source of PM2.5 pollution, exceeding PM2.5 emissions from power plants and vehicles in Colorado. These emissions are most substantial in rural areas where wood is burned for home heating.

As the state weans buildings off fossil gas, policies to support electrification of low-income households are crucial. Low-income residents face several barriers to electrification, including the high upfront cost of electric heat pumps and a lack of incentives for landlords to upgrade their rental housing units. If electrification lags in low-income communities, these communities are likely to shoulder the cost and burden of the remaining fossil gas infrastructure and pollution, exacerbating energy costs for people who already tend to spend a large share of their income on energy.

Figure: Energy Use for Buildings

Note: Pipeline gas is methane that is delivered to buildings via the gas distribution system. Today, that gas is entirely fossil gas, though the small amount that remains in 2050 may be replaced with synthetic gas in a deep decarbonization scenario.

Ensure New Buildings Are Efficient

Colorado’s residential building stock is expected to grow 16 percent by 2030 and 45 percent by 2050. Ensuring that these new homes are highly energy efficient and fully electric as soon as possible is critical to meeting our climate goals.

New buildings must be built with efficient building shells and efficient appliances from the start. Construction of new buildings must shift so that new homes are entirely or almost entirely built with efficient shells in the coming years. And more than 80 percent of new appliances (in existing and new buildings) must be energy efficient by 2030, up from less than 10 percent today.

Upgrade Existing Buildings

The state also needs to improve existing buildings with efficiency and electrification to meet the climate goals—these measures are key to ensuring equitable outcomes. Many Coloradans live in leaky or poorly insulated homes that waste energy, are uncomfortable, and exacerbate health issues. However, with improved building efficiency and electrification, occupants can see improvements in asthma, allergies, mold, and pests.

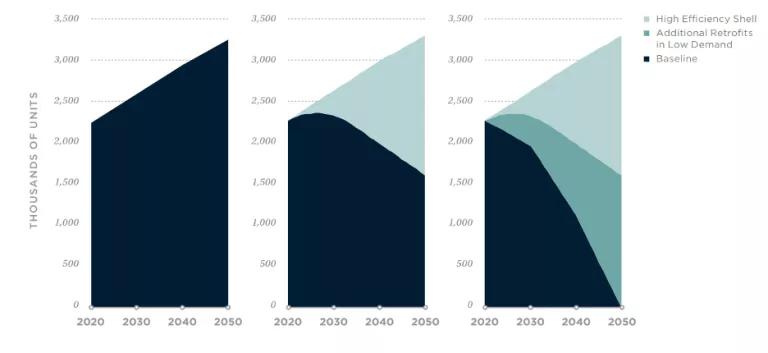

Our analysis shows that the state should upgrade 1 to 2 percent of homes per year over the next decade and more than 2 percent of homes per year after 2030 in order to meet the climate goals. If policymakers go even further on home retrofit programs, they can save Coloradans even more money on their energy bills, as shown by our “Low Demand” scenario. To achieve a bold program that retrofits every home in the state by 2050, Colorado should begin retrofitting almost 3 percent of homes per year this decade and more than 4 percent per year in the 2030s and 2040s.

The state also needs to move at a pace of replacing 2 to 3 percent of non-electric space heaters per year with efficient, electric ones in the coming years.

Figure: Residential Buildings With Efficient Building Shells

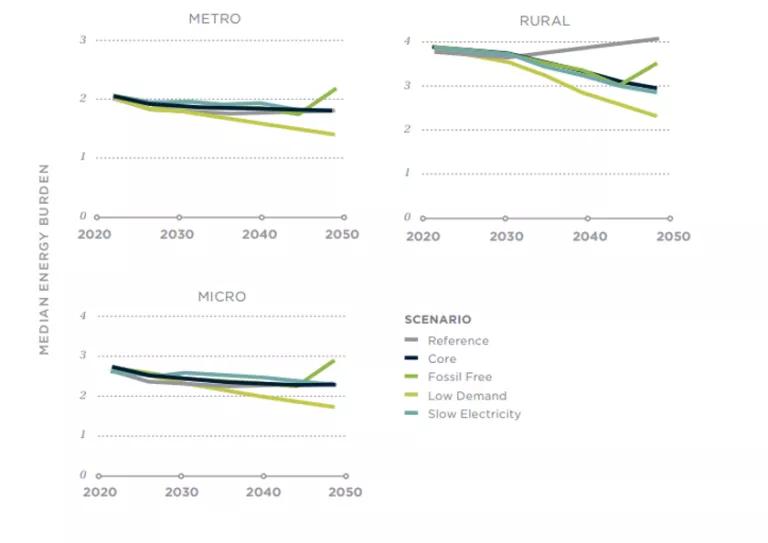

Our analysis also shows that investing in energy efficiency upgrades and electrification can cut energy burden for Coloradans, but in order to bring cost-saving improvements to the households that need them the most, policies must be designed to assist low-income communities in replacing their appliances and upgrading their homes.

Figure: Energy Burden in Modeled Scenarios

Getting on the Right Path

Policies for putting the state on the right path will include adopting building codes that move toward all-electric new construction, creating performance standards for existing buildings, and increasing electrification programs to help Coloradans purchase and install efficient electric appliances.

Through building codes, we have learned that the easiest and cheapest way to abate GHG emissions from buildings is to build clean from the start and avoid the costs of gas infrastructure. Specifically, all-electric construction is more affordable because it eliminates the need to connect gas lines, install gas meters, and pipe gas into the building. Putting in place building codes for all-electric construction will be critical to ensuring future buildings are part of the solution rather than part of the problem.

For existing buildings, we must focus on improving efficiency and electrifying. An existing building performance standard can require certain buildings to meet minimum energy or carbon efficiency requirements by a given date as a way to drive innovation and improvements over time. As for electrification, utilities can play a crucial role in developing electrification programs that provide incentives and simple strategies to help homes and businesses upgrade to electric heating, cooling, and cooking.

It is essential that all policies ensure Colorado’s low-income communities and communities of color are able to participate and benefit from these programs. This will require a process that is not only inclusive and equitable, but that specifically targets communities that have historically been burdened by high energy costs and pollution and unable to access clean energy programs. The processes must also work alongside fossil gas utility workers and their unions to reduce the impact to their jobs and support a transition to building and installing clean energy technology. This is an opportunity to take climate action in a manner that lifts up impacted communities and plans for addressing past inequities and preventing future burdens.

Crafting Building Policy in the Midst of an Eviction Crisis

Colorado—like the nation as a whole—is facing a housing and eviction crisis exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. Before the pandemic, 50 to 59 percent of renters in the Denver and Grand Junction metropolitan areas were cost burdened, paying more than 30 percent of their incomes for housing. In 2017, 38 percent of Coloradans were either living in poverty or were considered asset limited and income constrained. The pandemic worsened these underlying crises, driving unemployment rates to more than 12 percent in the state, leaving many renters unable to pay rent and utilities, and putting between 400,000 and 600,000 Coloradans at risk for eviction by the end of the year. This puts us in the midst of compounded coronavirus, climate change, and housing crises. Colorado leaders must protect all communities during the pandemic and beyond with an extension of the eviction moratorium, protections against displacement as a result of building upgrades, new policies to expand affordable housing, and opportunities to build wealth generation and ownership of homes and land among low-income communities and communities of color. These can include addressing the loopholes in the CDC eviction moratorium such as minor lease violations, lease terminations, and month-to-month tenancies. The state can also require landlords to support tenants by providing information on rental and legal assistance and reasonable repayment opportunities before an attempted eviction or collection, and to apply to Property Owner Preservation assistance before they can evict for nonpayment. Finally, late rental fees should be suspended until at least the end of 2020.

Building-sector climate policies are not only much harder to achieve in the context of rising housing insecurity and poverty, but also are at risk of deepening these crises without proper affordability protections, an expansion of tenants’ rights, and new frameworks for housing policy. Building shell upgrades and replacement of old appliances tend to increase the value of homes, driving up property values and rents and potentially leading to evictions and displacement. An advisory council could help prevent these negative impacts by bringing tenants rights’ and housing equity representatives as well as residents, workforce development organizations, representatives from labor unions, retrofit program implementers, joint labor-management apprenticeship programs, workforce training centers, and contractor associations into the planning process. The council can co-design solutions to avoid displacement and unaffordable housing and support green jobs.

By listening to those who are currently being impacted by unaffordability and pollution and those who will be impacted by the transition, we can ensure the development of concrete anti-displacement protections, affordability protections, and high quality job retention or creation. Only then can we build a just and equitable low-carbon economy.