All the Earmarks of Harmful Water Policy

NRDC findings show that communities of color most in need of water infrastructure funding are less likely to get it.

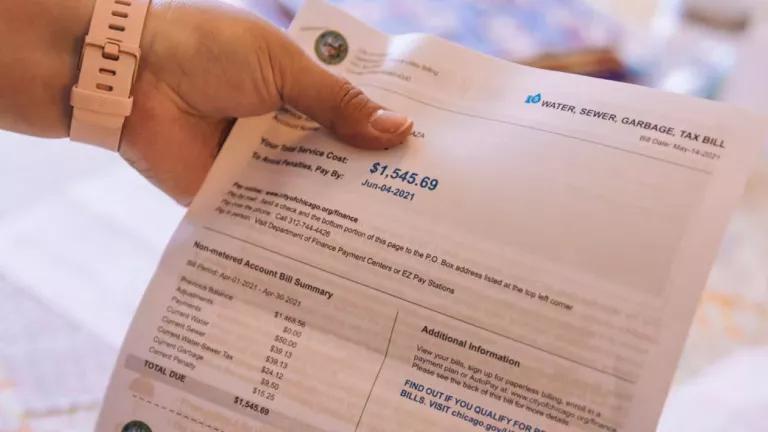

Shima Green for NRDC

Americans are deeply concerned about our drinking water and wastewater infrastructure; for example, a recent poll found that 7 in 10 voters think that lead pipes in drinking water systems are a “crisis” or “major problem.” And for good reason: the American Society of Civil Engineers gives our drinking water infrastructure a C- grade and our wastewater infrastructure a D+. Not exactly the report card you want to bring home to your parents. Unfortunately, recent actions by Congress—earmarking most of the funding for fixing water infrastructure so that it goes to politically favored projects—may undermine needed progress toward fixing these problems.

The problem with earmarks when it comes to state revolving funds

While Congress and the Biden administration made major investments in helping to address our crumbling and outdated water infrastructure in the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, that progress is at risk of being hindered. Congressional earmarks are a way for individual members of Congress to request direct funding for projects in their district during the appropriations process. Though earmarks have important applications in some contexts, they bypass what is supposed to be a merit-based or competitive allocation process under the State Revolving Funds (SRFs), threatening to disrupt access to needed monies by siphoning off most new appropriations to more politically potent projects. An additional problem with earmarks is that they often provide grants (or so-called loans with principal forgiveness) to communities that are not disadvantaged and that would otherwise only be eligible for loans. While true loans to wealthier communities must be repaid (revolving money back into the SRFs to be lent to other communities), earmarking grants to such communities means there’s less funding available to revolve back into the funding stream. So how exactly did this happen? And how can the program be improved to equitably deliver this funding?

Congress’s recent use of earmarks revives an old practice that had for years been paused in the wake of allegations (some fair, some not) of wasteful spending. Though the use of earmarks may well be beneficial in some contexts, its pitfalls in the context of water infrastructure seem clear. The Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC) recently noted that lawmakers have directed $1.47 billion of the total $2.76 billion SRF appropriation for fiscal year 2023 to 715 projects, which leaves just $1.29 billion for states to allocate. As Politico explained, “that means some states with powerful lawmakers are getting far more money from the State Revolving Funds than they would have under the traditional formula—and states with lawmakers who didn’t push for their home-state projects are getting far less.” A recent letter from a dozen water associations opposing additional earmarks emphasized: “These drastic cuts to annual appropriations have significantly undermined the transformational opportunity offered by the historic supplemental funding in the [Bipartisan Infrastructure Law].”

Earmarks like these are ultimately subtracted from the total amount appropriated to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), meaning every state that does not have earmarked funds headed its way misses out.

While some earmarks were provided to low-income communities with infrastructure troubles, like Benton Harbor, Michigan, and Jackson, Mississippi, other earmarks went to wealthier communities. And earmarks provide grants without any consideration of the amount of resources a community already has.

A recent report by my NRDC colleague Becky Hammer and her coauthor Katy Hansen at EPIC showed that communities with larger non-white populations were less likely to receive water infrastructure funds in recent years, even though communities of color, and specifically Black communities, are often the most in need of assistance to address infrastructure challenges. This is a problem under the SRF programs, independent of the earmarks issue, that must be addressed.

Previous commitments from the Biden administration have taken steps to address this inequity by promising that communities of color with crumbling water infrastructure will be prioritized for funding through the SRFs moving forward. But with earmarks reducing the pool of available resources, we’ve taken one step forward only to take a couple steps back.

President Joe Biden’s vision of every community having access to safe drinking water is attainable, but only if the billions of dollars being allocated are used equitably. Members of Congress—though they may well be acting with the best of intentions when it comes to their districts—are setting a troubling precedent by earmarking many of these funds, often away from the communities that need them most.

We are concerned that having most new funding allocated by earmarking will corrode the legally required systematic state public reviews and merit-based allocation of funding. While our recent report documents that the system is certainly imperfect and needs improvement, it has certain guardrails (including EPA regulations regarding priorities for the systems most in need, opportunities for public input and engagement, and the applicability of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act) that should help reduce the chance that these funds are allocated based primarily upon political power.

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law made progress—let’s not undermine that

The good news is that Congress and the Biden administration already enacted significant funding through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law in 2021, which is investing about $50 billion to address some of the urgent backlogs in necessary repairs and upgrades for the nation’s wastewater and drinking water systems. This is the single-largest investment in water that the federal government has ever made. And this money has not been subjected to earmarks and should be locked in for the next few years without them. It is the annual appropriation laws enacted since the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law that include Congressional earmark carve-outs that now redirect most of the new funding.

Let’s break the cycle of excessive earmarking

We join the water associations who urge that we “break this cycle” of diverting EPA funding for water infrastructure to earmarks. Congress should fund at least the full authorization—$3 billion each—for the Clean Water and Drinking Water SRFs next year. If earmarks are used for water infrastructure, the funding underlying such earmarks should be in addition to the authorized $3 billion per year for each SRF and should not cut into that crucial funding that should instead be directed to the communities that are demonstrably most in need.

More information:

- NRDC & EPIC, A Fairer Funding Stream: How Reforming the Clean Water State Revolving Fund Can Equitably Improve Water Infrastructure Across the Country

- EPA’s 6th Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment

- EPA 2012 Clean Watersheds Needs Survey

- American Water Works Association, Buried No Longer: Confronting America’s Water Infrastructure Challenge Report