View into an Illinois state prison cell, which holds an open toilet in close proximity to bunk beds.

Alan Mills/Uptown People's Law Center

When people incarcerated at the Vienna Correctional Center in Southern Illinois (“Vienna”) turn on the water in their cells, it often comes out brown. Particles float in this water, and it smells like fish or sewage. If you had a choice, you would never drink it — but the people in prison at Vienna have no choice. No water is available besides that which the Illinois Department of Corrections (“IDOC”) chooses to provide to them.

Since Fall 2021, NRDC has been working with other environmental groups, grassroots environmental organizations, abolitionist groups, and advocates for people in prisons — including the Coalition to Decarcerate Illinois, Equity Legal Services, Illinois Alliance for Reentry & Justice, Illinois Environmental Council, the John Howard Association, Little Village Environmental Justice Organization, Loevy & Loevy, Sierra Club Illinois Chapter, and Uptown People’s Law Center — to uplift the pervasive concerns voiced by people in prison about drinking water contamination and failing sanitary systems in Illinois prisons like Vienna. The members of this coalition include people who are currently or formerly incarcerated — like Broderick Hollins, who was diagnosed with lead poisoning after 4 years at Stateville Correctional Center, about an hour southwest of Chicago — as well as people with family and friends who are currently or formerly incarcerated. As Broderick describes in a recent op-ed, these coalition members know firsthand what it means for themselves and their loved ones to be exposed to unsanitary conditions day after day while under the “care” of the State.

Together, the coalition has helped to shed light on conditions that support what people in prison have been saying for years: IDOC’s water and sanitation infrastructure is neglected, deteriorating, and cannot safely serve tens of thousands of imprisoned individuals. And the state regulator primarily responsible for ensuring that drinking water is safe, the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (“IEPA”), has largely ignored those conditions. The coalition is now working to bring these environmental justice issues to the attention of the public, regulators, and elected officials. Together, this intersectional effort is demanding action that will safeguard the health of those who are forced to rely on this contaminated water for all of their needs — and more broadly, calling for an end to inhumane incarceration.

Vienna is one of the IDOC facilities on which we have focused our information-gathering efforts. Unlike some prisons that receive their water from the nearest city’s water treatment facilities, Vienna sources its water from a nearby lake and manages water treatment itself. This treatment has been shoddy, to say the least, and our coalition learned of algal blooms in the lake that could lead to the presence of harmful bacteria called cyanotoxins in drinking water.

When U.S. EPA inspected Vienna, they found the raw water retention tank leaking; the leaks had been plugged with sticks of wood.

United States Environmental Protection Agency, Region 5

IDOC’s security protocols make it functionally impossible for incarcerated users or members of the public to directly inspect the water system, short of litigation. Advocates cannot simply walk on-site and test the source or tap water for suspected contaminants. Instead, the coalition has relied upon a combination of reporting by individuals imprisoned at Vienna, and disclosure of inspection reports by regulatory agencies who can access the site. While the latter are often thin on detail (partly because of regulatory gaps and shortcomings in enforcement actions for prison water systems), the IEPA documents that the coalition obtained prior to Fall 2022 indicated cause for serious, justified concern and spurred us to further investigation.

IEPA has made little effort to solicit and investigate the testimony of those closest to and most affected by the water: the people imprisoned at Vienna. To better understand the conditions under which IDOC forces the people imprisoned at Vienna to live, and with the input of other coalition members, NRDC and Uptown People's Law Center circulated a survey in Fall 2022 asking 551 people in prison at Vienna to self-report about the quality of the drinking water and to describe any health issues they have been experiencing that may connect to the water.

The resulting information, gathered from 133 respondents (about 23% of people incarcerated at Vienna in early 2023), helps to illuminate what IDOC forces people to live with while imprisoned at Vienna by centering the voices and experiences of those affected — a perspective that is routinely overlooked by regulatory bodies despite being essential to the delivery of safe and clean water. The responses received by our coalition contribute to an evidence base that calls for regulatory bodies who do have access to carry out a more thorough investigation of what is going wrong with Vienna’s water and take immediate steps to protect people in prison.

Water Quality at Vienna

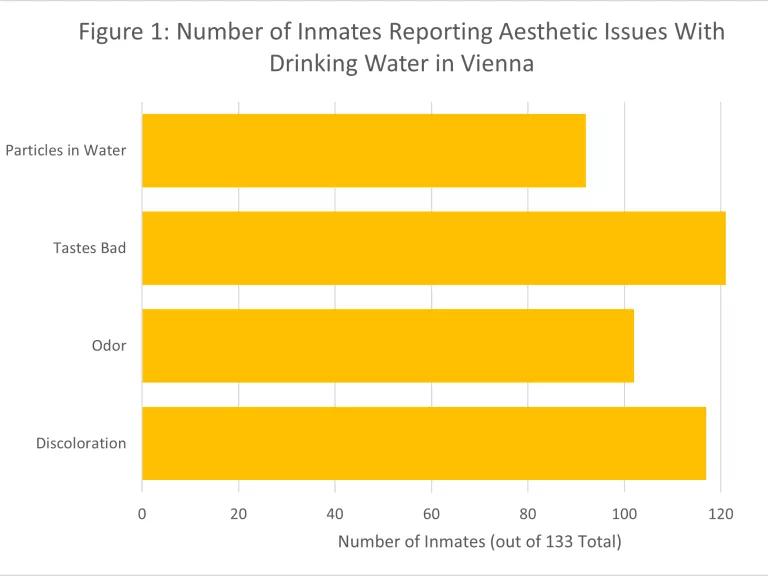

In the survey, we asked incarcerated individuals to report whether they observed that the drinking water at Vienna had a bad taste; was discolored; had an unusual odor; or contained visible particles.

The vast majority of people imprisoned at Vienna who responded to our survey observed visual problems with the drinking water.

Out of the 133 respondents, 94% said they observed at least one of these problems with the water. As Figure 1 shows, 91% of respondents said the water tastes bad; 88% noted discoloration; 77% observed an unusual odor; and about 70% of respondents saw particles in the water.

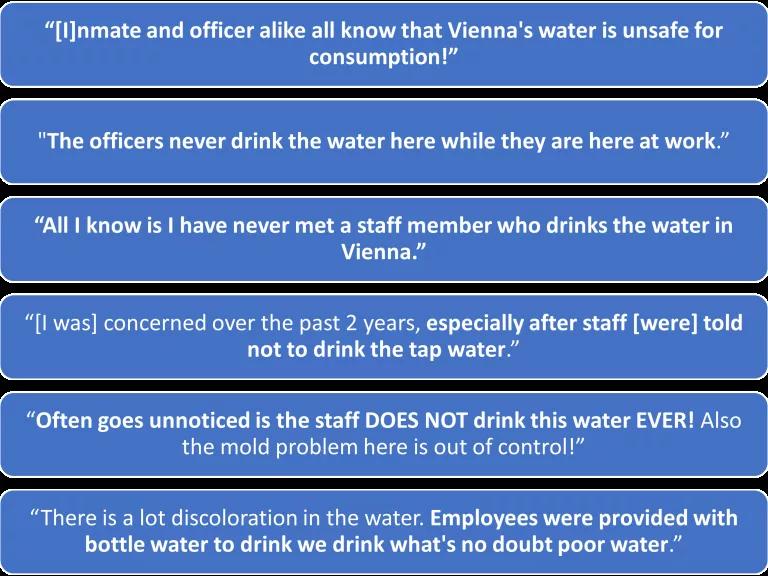

In the space we provided for individuals to describe any other observations about the water, several respondents said they noticed that correctional staff avoid the tap water or carry bottled water. While those who are incarcerated have no choice but to drink the tap water provided, correctional staff have access to alternatives—that they are using these alternatives may be telling.

Figure 2: Quotes from incarcerated respondents about correctional officers' water bottle use at Vienna

Health Issues at Vienna

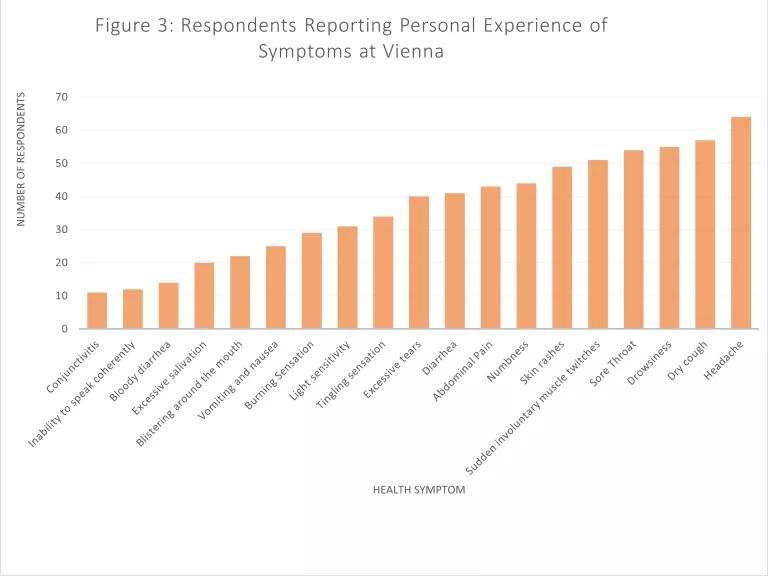

We also wanted to use this survey to see what health issues people imprisoned at Vienna observe and whether they connect those symptoms to the water, both personally and with respect to those around them. We asked people at Vienna to report whether they experience a variety of health symptoms, including certain gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms that researchers associate with the consumption of cyanotoxins as well as other forms of harmful bacteria that can get into water systems, like E. coli.

Survey respondents reported experiencing a variety of health symptoms while at Vienna.

As Figure 3 shows, many respondents are themselves experiencing multiple health symptoms. The reports of health symptoms respondents observed in their peers mirrored the chart above. The top health symptoms that respondents reported experiencing personally included symptoms associated with multiple types of cyanotoxins. In particular, out of the 51 respondents who reported experiencing muscle twitches, 39 also reported experiencing numbness, which could indicate a greater likelihood that these symptoms have a neurological cause associated with certain cyanotoxins. We further noted that 49 respondents reported experiencing skin rashes, and several described itchiness, bumps, and peeling in their accompanying narrative responses.

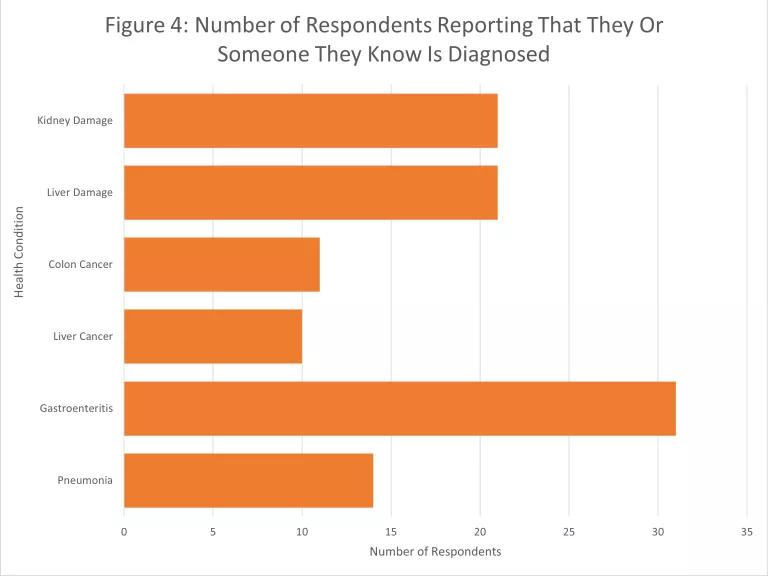

We also asked the survey respondents to report whether they have been diagnosed with certain health conditions that researchers associate with cyanotoxins and other water contaminants. These questions received fewer responses, which is consistent with the comments many respondents included about difficulties obtaining medical care.

Several of the people in prison at Vienna who responded to our survey reported either being diagnosed or knowing someone who has been diagnosed with gastroenteritis.

Figure 4 shows the responses we received as to how many people were either personally diagnosed with a health condition of interest or know someone else at Vienna who has received such a diagnosis. A substantially higher number of respondents reported being diagnosed with, or knowing someone who is diagnosed with, gastroenteritis—a health condition that is connected to a type of cyanotoxin called microcystin, as well as to other harmful bacteria like E. coli.

A few months after we sent these surveys to Vienna, and approximately one year after our coalition formed to advocate together on this matter, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (“USEPA”) intervened and conducted its own inspection of Vienna. USEPA found that critical components of the treatment plant had “deteriorated beyond a maintenance level” and now required immediate repair. Given Vienna Correctional Center Lake’s propensity for harmful algal blooms, USEPA’s diagnosis of a collapsing drinking water system was especially troubling. The system failures identified at Vienna can also increase risks of exposure to Legionella and other harmful forms of bacteria in the water. (Of note, according to USEPA reporting on a discussion with Vienna staff during the agency’s inspection, Vienna tested positive for Legionella at multiple sample locations in 2022.)

Where Do We Go from Here?

Due to the limitations noted above, our survey was not intended to generate data from which we could draw statistically significant inferences or draw firm conclusions about causal relationships. The survey responses simply provide an informative snapshot of the water conditions and health issues people imprisoned at Vienna are experiencing. But that snapshot is a horrific one—and it merits rapid response by environmental regulators to systematically investigate the situation and make sure that drinking water quality at Vienna is restored. And IEPA, the regulator primarily responsible for acting on this information, has not demonstrated an interest in discussing these results. Our coalition arranged to present this information to USEPA and IEPA in March 2023, but one business day before the meeting, IEPA informed us that they would no longer attend.

Ultimately, the people who know the most about the conditions at Vienna are the people incarcerated there—and they also know best what is happening to their physical and mental health as they continue being forced to live with these conditions.

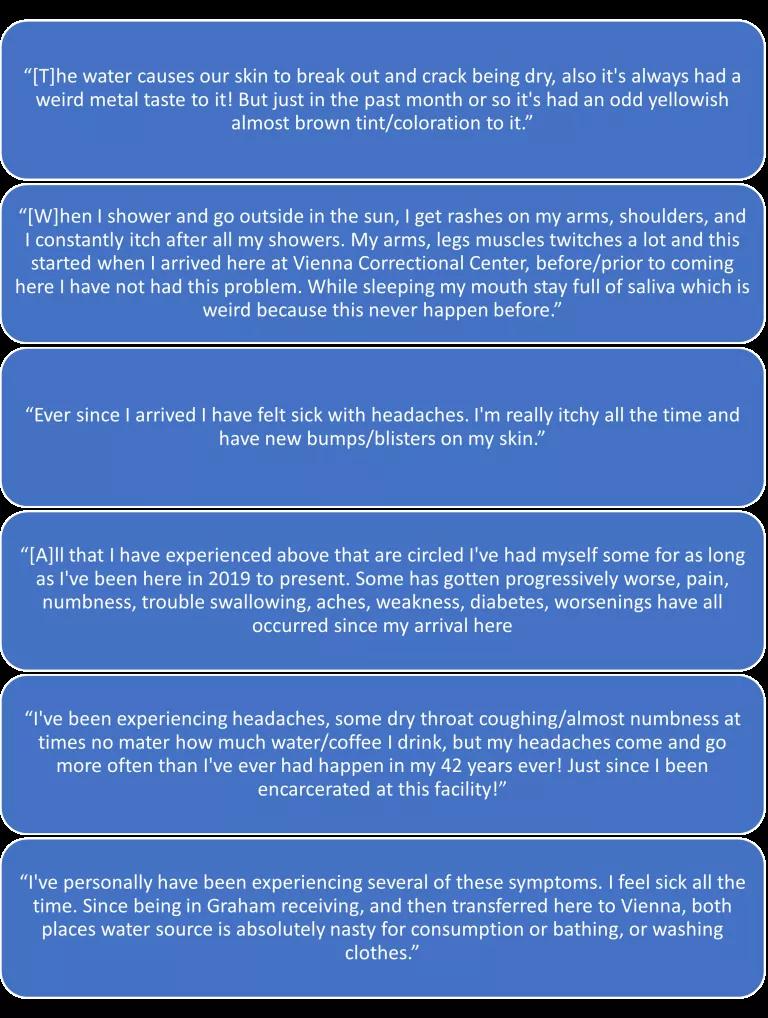

Figure 5: People imprisoned at Vienna describe their experiences with the drinking water and with painful symptoms in response to our health survey.

All of these reports came from just one prison. But our coalition has heard similarly troubling reports about many others; rather than an exceptional case, our investigations into Vienna illustrate a systemic pattern of cruelty and neglect. In Illinois, sentencing a person to prison effectively means sentencing them to years, decades, or a lifetime of foul and sickening water. Advancing environmental justice means demanding that these practices end.