We Saved the Ozone Layer. We Can Save the Climate

Climate change is not the first planetary pollution crisis we have faced. That distinction belongs to the depletion of the earth’s protective ozone layer. And how we solved the ozone crisis teaches lessons for climate change.

I'm updating this 2012 post on the occasion of the new documentary airing on PBS: "Ozone Hole: How We Saved the Planet". It's the best telling of the nearly 50-year story of scientific discovery, citizen action, diplomatic leadership, and technical innovation—all the ingredients we need to solve the climate crisis. Read on, and then watch it!

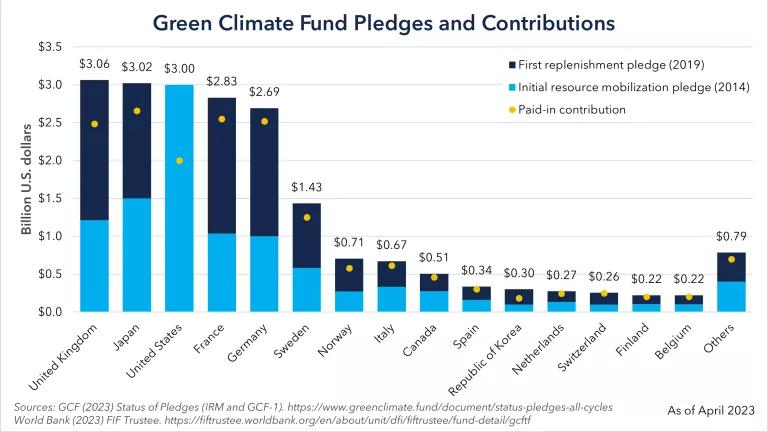

A visualization of the ozone hole over Antarctica in 2015

Goddard Space Flight Center/NASA

Climate change is not the first planetary pollution crisis we have faced. That distinction belongs to the depletion of the earth’s protective ozone layer.

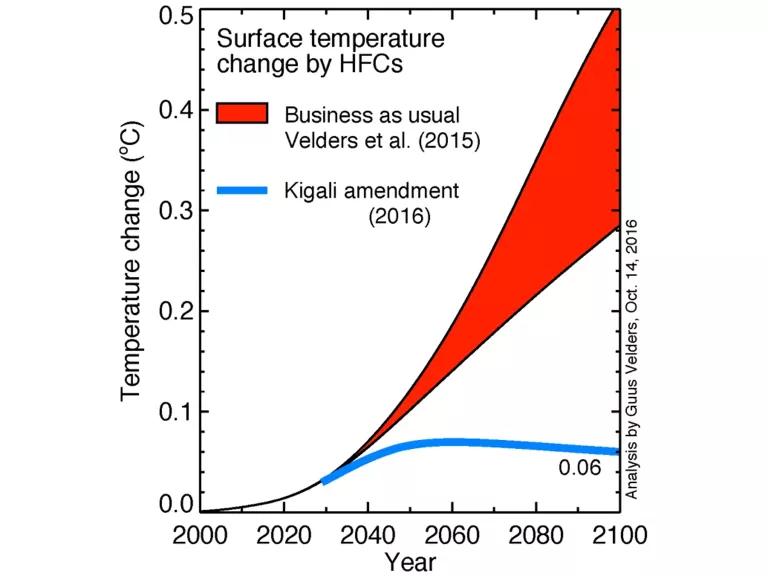

Thirty-two years ago, countries signed the world’s most successful environmental treaty, the Montreal Protocol. That’s the treaty that saved the ozone layer, saved millions of lives, and avoided a global catastrophe.

We too often take the rescue of the ozone layer for granted. A whole generation has grown up not hearing much about it, except maybe once each September when the return of the Antarctic ozone hole gets a brief mention in the news. As we struggle to curb the carbon pollution that’s driving climate change, it’s worth remembering, and learning from, our success in solving the ozone crisis.

As beautifully told in the new documentary Ozone Hole, the story begins nearly 50 years ago when two chemists, Sherwood Rowland and Mario Molina, discovered that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) released from aerosol sprays could rise miles over our heads into the stratosphere. There, the sun’s harsh rays split the CFCs apart, triggering reactions that destroyed ozone molecules. As the ozone shield weakened, more dangerous UV rays could reach the earth’s surface. That would have condemned millions of people worldwide to die from skin cancer, go blind with cataracts, or suffer from immune diseases.

Their discovery made big news and galvanized Americans. Aerosol sales plummeted, as millions of consumers switched to pump sprays and roll-ons. Some companies quickly redesigned their products. But others dug in. For more than a decade, the chemical companies that made CFCs reacted much like today’s coal and oil companies: They denied the science, attacked the scientists, and predicted economic ruin.

But scientists and lawyers at NRDC—well before I got here—fought back. They helped Rowland and Molina tell their story to Congress and the news media. They pushed for bans on CFC aerosols here at home and pressed the United States to demand the same from other countries.

Rowland Sherwood (left) in the lab at the University of California, Irvine, with Mario J. Molina, January 1975. Twenty years later, they shared the Nobel Prize in chemistry.

University of California Irvine Special Collections Library

In the late 1970s, the public demanded action and the government responded. Congress added ozone layer protections to the Clean Air Act, federal agencies mopped up the last aerosols, and the State Department began working with other nations on a treaty. In 1980, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued an “endangerment” finding, saying that the other uses of CFCs in refrigerators, air conditioners, and industrial processes also posed a threat to the ozone layer and to public health.

But when Ronald Reagan took office, things bogged down. Those of you who remember Anne Gorsuch and James Watt will know that protecting the ozone layer was not a priority in Reagan’s first years. The EPA did nothing, treaty talks stalled, and CFC use rebounded, so by the mid-1980s, production was back to its 1974 peak and rising fast. The danger was growing again.

So I and an NRDC colleague, Alan Miller, sued the EPA under the Clean Air Act, because the agency was obligated by the endangerment finding to issue CFC regulations. Once William Ruckelshaus replaced Anne Gorsuch at the helm of Reagan's EPA, the agency to its credit followed the science and settled our lawsuit with a plan of action. The EPA worked with NASA and other agencies to amass a compelling, peer-reviewed scientific assessment. The EPA brought together industry and environmentalists and others to agree on alternatives. The State Department restarted treaty talks.

Congress held hearings in the mid-1980's under the bipartisan leadership of Senators Max Baucus, John Chafee, and Al Gore, and Representatives Henry Waxman and Sherwood Boehlert, keeping the danger in the public eye. And the news media covered the story, without giving equal time to marginal skeptics.

The surprise discovery of the Antarctic ozone hole in the mid-1980's added new urgency. Within a year, NASA scientists led by Susan Solomon, now at MIT, nailed the connection between CFCs and the ozone hole. By 1986, even the chemical industry acknowledged CFC limits were needed.

In 1986, I proposed the idea of a 10-year global phaseout—to start using available alternatives immediately and to create market incentives to rapidly perfect and deploy solutions for the remaining uses. Again to their credit, Reagan’s next EPA administrator, Lee Thomas, and Secretary of State George Schultz put a phase-out plan on the international negotiating table.

Yet not everybody was on board. Interior Secretary Donald Hodel urged Reagan to tell people to just wear hats and sunglasses. (My role in exposing Hodel's "Rayban Plan" is told starting at the 31:30 mark in the Ozone Hole documentary.) His plan became a punchline. Reagan, who himself had had skin cancer, continued to back the treaty.

And in September 1987, countries reached agreement on the Montreal Protocol. By 1990 it had been amended to become a global phaseout agreement. That same year Congress added strong ozone safeguards to the Clean Air Act.

Every president since Reagan has supported the treaty; every country on earth, from China to East Timor, is now a full party.

Rowland and Molina received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995.

It is not easy to convey the scale of the catastrophe that was avoided, the disaster that did not happen. This is what NASA scientist Dr. Paul A. Newman has accomplished in his extraordinary analysis, “The World Avoided.” You can read about it here, and you can watch Dr. Newman’s presentation at an NRDC press event in 2012. (A more sophisticated animation of Dr. Newman's findings is shown in Ozone Hole starting at 41:30.)

Millions of lives saved. Hundreds of millions of cancers averted. Agricultural disaster avoided. These are big achievements.

But our work is not done. Here are a few thoughts on what we still need to do under the Montreal Protocol and on lessons from the ozone treaty for the fight against climate change.

First, as Dr. Newman has shown, the ozone layer is healing. While countries have committed phasing out the last ozone-depleting chemicals, we have to keep our eye on the ball to make sure it happens on schedule. And while national compliance with Montreal commitments has been extraordinarily high, governments have to work harder to crack down on law-breakers and smugglers. If we stick with it, scientists expect the Antarctic ozone hole to close up for good later this century.

Antarctic Ozone Hole 1980 through 2018, courtesy NASA

Second, we can do more under Montreal to fight climate change. There’s already been a climate change bonus. The CFCs were also extremely powerful heat-trapping pollutants, and replacing them has slowed climate change by a decade. Had we not acted, the world would already be suffering even more severe droughts, wildfires, floods, and storms. The extreme weather we're suffering year after year would have been even worse.

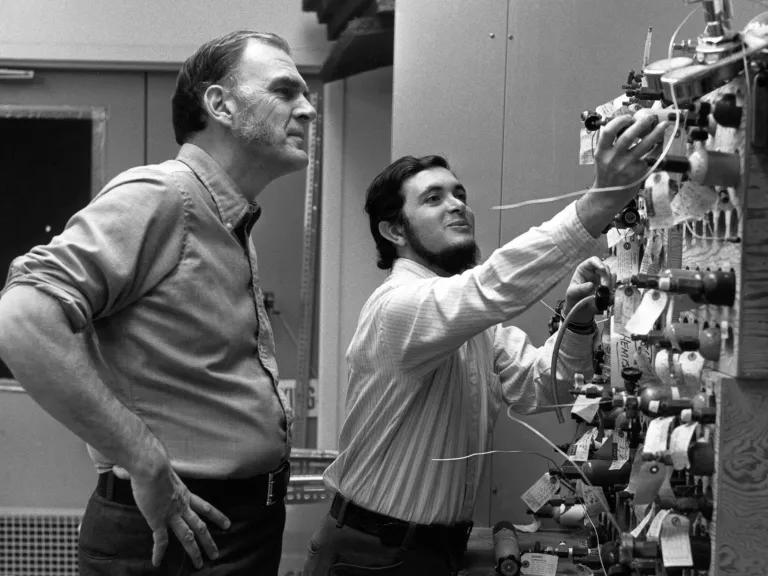

But one group of CFC replacements, called HFCs, poses a big problem. HFCs are also powerful greenhouse gases, and Dr. Newman’s science panel has estimated that if we let them keep growing, by midcentury they’ll trap as much heat as CFCs did at their peak. Another scientific team showed that if left unchecked they could add nearly half a degree centigrade to global warming by 2100, making it even harder to hold the overall warming to 1.5 degrees, or even 2 degrees, beyond which climate impacts become catastrophic.

Velders, et al.

Wisely, the Montreal Treaty gave the parties the responsibility to ensure that replacement chemicals are safe—and that includes ensuring that they don’t magnifying climate change. So 10 years ago, two groups of countries—a group of island nations led by Micronesia, and the United States, Canada, and Mexico—proposed using the Montreal Protocol to phase down HFCs.

It took a decade of education and tough negotiations, but in October 2016 the nations of the world agreed on the Kigali Amendment to phase down HFCs by 85 percent worldwide over the coming decades. Once again, countries came together following the proven formula under the Montreal Protocol, with all countries committing to cut their emissions, as developed countries take the lead and help fund action in developing countries.

The NRDC team in Kigali when the HFC Amendment was adopted

NRDC

The Kigali Amendment has been ratified by more than 60 countries and came into effect on January 1, 2019. The Trump administration said in 2017 that it supported the agreement's goals and approach and was considering ratification. The HFC phase-down has broad industry and bipartisan support—13 GOP Senators wrote the president last year urging ratification and a bipartisan phase-down bill was also introduced. But the administration has made no decision yet. That's better, of course, than Trump's outright rejection of the Paris Climate Accord, but it still leaves the U.S. in limbo.

So NRDC has embarked on getting leading states to take action. California passed HFC legislation last September, and Washington State is on the brink of enacting its own bill. New York, Maryland, and Connecticut have committed to HFC restrictions under existing laws, and many other states in the U.S. Climate Alliance are considering identical laws or regulations.

There will be another bipartisan push for federal HFC legislation this year, with surprising allies running from NRDC to the National Association of Manufacturers.

Meanwhile, the industry continues adopting climate-friendlier alternatives to HFCs.

So, even in these difficult times, the Montreal Protocol stands out as proof positive that the earth’s nearly 200 countries can effectively cooperate to protect their citizens from a planetary pollution crisis—address climate change as well as ozone depletion.

We saved the ozone layer. We can save the climate.