NRDC Briefs Congress on Neonic Pesticide Human Health Harms

I am pleased to be able to brief Congressional staff—both the House and Senate side—on the potential for adverse human health harms from neonicotinoid pesticides, or ‘neonics’. NRDC is one of a coalition of environmental groups—including Friends of the Earth (FOE US) and Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER)—supporting two bills that will help address the toxic impact of neonics:

- The Protect Our Refuges Act (H.R. 2854). Led by Rep. Velazquez (D-NY), it prohibits all uses of neonics on protected lands or wildlife refuges.

- Saving America’s Pollinators Act (H.R. 1337). Led by Rep. Blumenauer (D-OR), it requires EPA to cancel registrations of neonicotinoids and other systemic insecticides, and to track and report on the health of native bee populations.

Neonic insecticides are the worlds most widely-used insecticides, designed to kill insects through a nerve-damaging mechanism with disturbing similarities to deadly war-era organophosphate pesticides like chlorpyrifos that the neonics are replacing.

One of the main reasons that neonics are so harmful is that they are designed to be systemic—that is, to get into the system of the plant, making the pollen, nectar, and other parts of the plan toxic to insects. And, they are long-lasting, leading to toxic residues in the soil and waterways around the world.

By replacing chlorpyrifos and other deadly organophosphate pesticides with neonics, have we gone from the pan to the fire? Or, maybe more accurately, from crackling flames a slow deadly burn?

Neonics already have a bad reputation for killing bees, aquatic invertebrates, songbirds (through ingestion of neonic-coated seeds), and other beneficial insects and wildlife. In fact, estimates are that US agriculture is 40 times more toxic to insects, largely due to the introduction of neonics (DiBartolomeis et al 2019).

Neonics also pose a threat to human health. It's not only the birds and bees that can be harmed by neonics, but even people need to be careful!

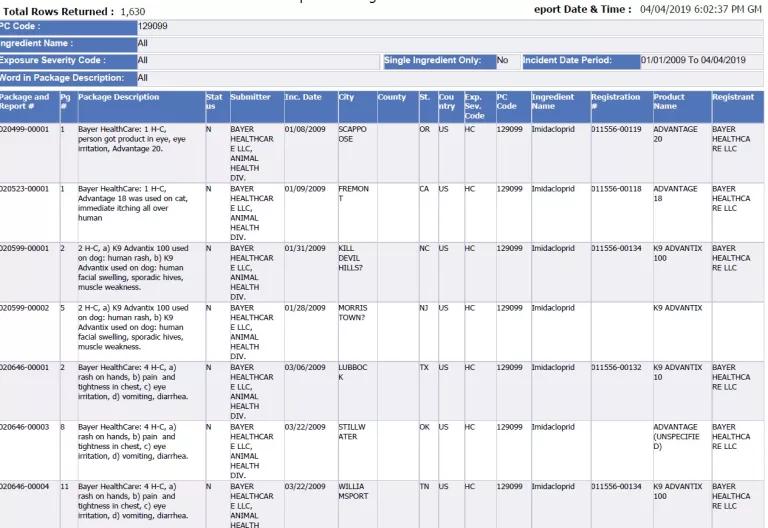

The EPA aggregates pesticide poison reports, and its data show that some of the worst offenders are the neonics, used in homes, gardens, and for pet flea and tick treatments. Imidacloprid alone was linked to over 1,600 poisoning reports over the last decade (Data provided to NRDC in response to FOIA Request No. EPA-HQ-2019-004044).

Neonic poisoning reports include the following acute symptoms:

- Clothianidin – numbness, chest pain, headache, muscle weakness and tremors, shortness of breath, sore throat, coughing, skin rash and itching, tachycardia (rapid heart rate), blurred vision, abdominal pain;

- Imidacloprid – rash, muscle tremor, difficulty breathing, vomiting, wheezing, lock jaw, memory loss, renal failure;

- Thiamethoxam – throat irritation, skin irritation and rash, fever, numbness, dizziness, diarrhea, sweating (note that the major metabolite of thiamethoxam is clothianidin).

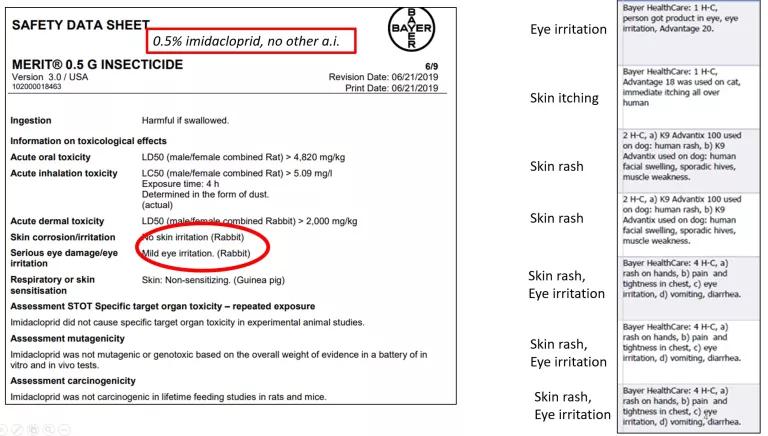

Although many of the poisoning reports include skin irritation, the Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) that is required by law to inform the public about the hazards of chemicals, fails to alert the public that skin irritation is a potential symptom of poisoning (see BAYER MSDS image).

In addition to the reported acute poisonings, there are numerous scientific studies raising concern regarding potential chronic toxicity from neonic exposures, particularly during early life development. In this way, the neonics are similar to the organophosphate pesticides like chlorpyrifos that they replace. Both chemical classes are neurotoxic, meaning they interfere with the function of the brain and nervous system. This is particularly relevant to early-life risks, because it is a well-established fact (see Project TENDR Consensus Statement for evidence) that people are most sensitive to neurotoxic agents when exposures occur during early life brain and nervous system development (for example, lead and mercury are most harmful during this developmental period).

Evidence for potential chronic human health impacts includes the following:

- Studies of unintentional human exposures – Developmental or neurological effects of neonics may include malformations of the developing heart and brain, autism spectrum disorder, and a cluster of symptoms including memory loss and finger tremors (Cimino et al, 2017).

- Laboratory animal studies – neonic dosing to rodents resulted in neurobehavioral deficits in offspring that were exposed during fetal brain and nervous system development (Abou-Donia et al, 2008).

- Wildlife studies - Developmental abnormalities in white-tailed deer experimentally exposed to environmentally-relevant levels of imidacloprid in their water had a higher risk of hypothyroidism and lethargy, decreased body and organ weight, decreased jawbone length, and higher mortality rates for fawns (Berheim et al 2019, Nature).

Neonic residues contaminate food and drinking water, and our bodies!

In addition to the home, garden and pet uses that lead to harmful exposures documented above, people can be exposed to neonic pesticides through contaminated tap water and food. Neonic residues are found in common foods including kid’s favorites such as apples, cherries, honey, strawberries, and baby food (Craddock et al, 2019; FOE 2019). The systemic nature of the chemicals means the residues are within field-treated fruits and vegetables and are not removed by washing or peeling.

Data from over 3,000 individuals included in the 2015–2016 US government national health and nutrition examination survey reported that half the US population above 3 years old are exposed to neonics on a regular basis, as evidenced by neonic metabolites in human urine samples (Ospina et al 2019).

Moreover, young children had higher levels than adults on average, raising red flags given the risks that the chemicals pose to nervous system development (discussed above).

The good news is that most uses of neonics aren’t needed.

Neonic corn and soybean seed treatments—a neonic coating that comes on the seed sold to growers—provide little to no benefits to farmers, but account for most of the neonic used in the US (Mourtzinis et al, 2019; Tooker et al, 2017). Some neonic uses may actually decrease crop yields by killing beneficial insects like pollinators and crop pest predators (Douglas et al 2014). For example, in one study, farms using neonics and other conventional chemicals had ten times the insect pressure and lower profits than farms using regenerative practices (LaCanne and Lundgren, 2018).

Unfortunately, the EPA is failing to protect US families by disregarding potential developmental risks posed by neonic pesticides.

EPA does not currently consider the neonicotinoids as a cumulative assessment group under the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA) because EPA does not believe that the class of neonic chemicals share a “common mechanism of toxicity.” By evaluting each neonic alone, instead of the risks posed by the cumulative exposure to multiple neonics together—as occurs in the real world and is proved by the urine biomonitoring evidence—EPA can set each exposure limit much higher, permitting more residue on our food and in our drinking water.

In addition, EPA has failed to apply important child-protective provisions of the FQPA to neonics. EPA has done this despite acknowledging for imidacloprid that, “evidence of increased qualitative susceptibility in the rat developmental neurotoxicity study.” FQPA passed Congress unanimously, and is intended to be applied to protect US families—EPA’s failure to use the law is a failure of public trust.

That’s why Congress is proposing two bills that will put the brakes on the unnecessary overuse of this harmful class of systemic pesticides to protect people, pollinators and other wildlife.