With Family Roots in the Mines, He’s Championing Illinois’s Clean Energy Future

With grassroots groups and other partners, J. C. Kibbey is fighting for one of the country’s most ambitious climate bills—and a just transition away from coal.

A worker repairs a power generating wind turbine near Dwight, Illinois.

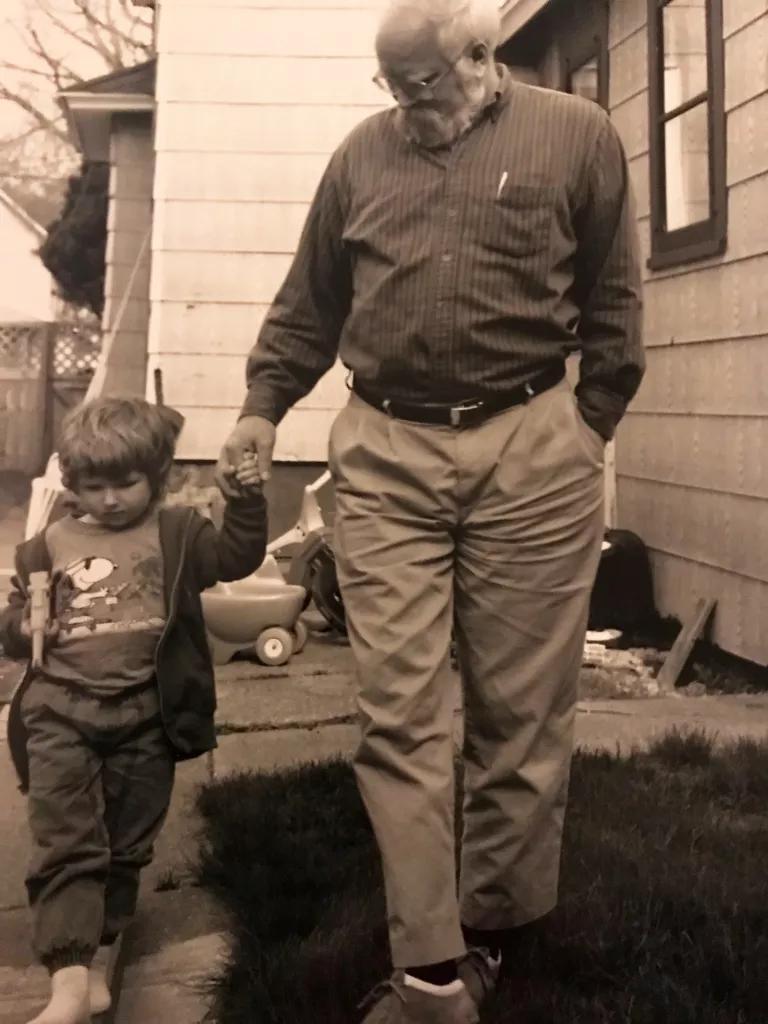

Coal has always loomed large for J. C. Kibbey. He grew up hearing stories about the lives of family members whose work revolved around it—including his great-grandfather, who toiled in Appalachian coal mines; his grandfather, who sold rail chassis used to transport coal from Wyoming’s Powder River Basin; and his dad, who did community and economic development work in a former coal company town in Kentucky. He also knows firsthand what it’s like to grow up in the shadow of a coal plant: Three were located within walking distance of his childhood home in Lansing, Michigan. And back then, Kibbey was often sick with respiratory problems, likely caused by the pollution that surrounded him.

Kibbey also remembers what happened when one of those coal plants ceased operations in the early 1990s. Local residents suddenly found themselves out of work, and a massive, unused site with a deteriorating building would scar Lansing’s downtown for the rest of his childhood.

Today, as an Illinois clean energy advocate at NRDC, Kibbey holds those workers front and center as he strives to ensure a just, equitable, and lasting transition for the communities impacted by plant closures. It’s critical work as companies rapidly shutter their plants across Illinois, part of a nationwide trend that saw a nearly 40 percent decline in U.S. coal generation in the last decade.

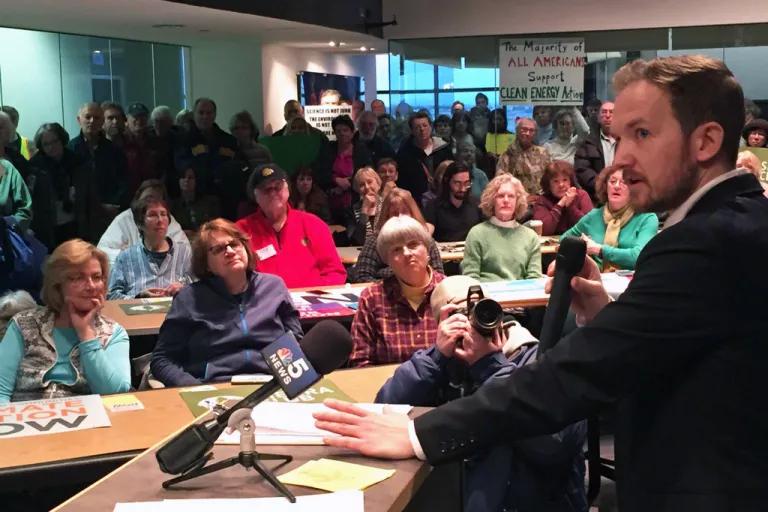

To address these challenges, state lawmakers introduced the Clean Energy Jobs Act (CEJA) last February. Developed with the input of residents across Illinois in more than 70 town hall meetings, the legislation would move the state to 100 percent renewable energy by 2050 and make it a national leader in clean energy and climate action. The bill also calls for cleaning up Illinois’s transportation sector and, importantly, prioritizes equity throughout.

“We need to make sure that we’re centering the needs and interests of the most impacted communities in our transition to a clean energy economy,” Kibbey says. “And that we’re trying to make right, as much as we can, all of the negative impacts people have suffered.”

CEJA aims to do that by investing more than $200 million in job training, economic development, and property tax replacement funds; providing incentives to attract renewable energy development; and offering support for cities and towns working to create their own plans for a clean energy future.

While Kibbey notes that the closure of coal plants unquestionably spells good news for people’s health and the climate, “if you don’t handle what happens after the closure the right way, it looks like a big, rotting hulk in the middle of your downtown.” While the shuttering of the Ottawa Street Power Plant in Lansing did cause that urban distress, the city ultimately turned its plight around. After sitting vacant for 15 years, the plant was finally redeveloped in 2007 as corporate headquarters for the Accident Fund Insurance Company. The project—a shining example of community revitalization—achieved LEED Gold Certification for its environmentally friendly building design, and the former plant now houses 500 good-paying jobs while also beautifying a landmark in a previously struggling downtown.

“I know that every coal community is different, so I don’t mean to say that what worked in my hometown is going to work everywhere. But to see a solution that worked is encouraging,” Kibbey says. “A lot of the work that we’re doing with the Clean Energy Jobs Act to move Illinois away from fossil fuels and toward the clean energy economy is exactly for people who live in towns like the one I grew up in.”

Ivan Moreno, a strategic communications manager who works closely with Kibbey in NRDC’s Chicago office, notes that Kibbey’s personal connection to his work makes him an effective advocate for legislation like CEJA. “It’s inspiring to see how J.C. has been able to translate his family’s experience of living and working in the heart of the coal industry into advocacy for a clean energy transition that will spare communities the terrible health effects of coal.”

Kibbey’s firsthand experience with the impacts of the coal industry no doubt led him to this work, but he also cites the 2006 documentary An Inconvenient Truth, which sounded the alarm on the climate crisis, as another key influence. After studying political theory in college, he moved to Chicago to pursue a master’s degree in public policy at Northwestern University, where he focused on climate change. Following in his father’s organizing footsteps, he worked for SEIU Local 1 and joined the Union of Concerned Scientists as a policy advocate in 2016 before landing at NRDC in late November 2018.

From his Chicago office, Kibbey has forged relationships with local grassroots and environmental justice groups, as well as other large environmental organizations like the Sierra Club, to make the push for an equitable transition to 100 percent renewable energy in Illinois. Several factors, including a new governor who supports this larger goal, helped shift the political landscape enough to bring CEJA about. He credits the community groups in the Illinois Clean Jobs Coalition—including the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization, Clean Power Lake County, and the Central Illinois Healthy Community Alliance, to name just a few—with making sure that people who will be most impacted by coal plant closures are involved from the beginning. He notes that those on the “traditional environmental advocate side” have learned a lot of lessons in that respect. Moreno adds that the coalition of advocates has also grown, in part, thanks to the work of Kibbey. “The coalition benefits greatly from J. C.’s leadership style of listening and brings people to the table.”

Kibbey has also worked with the Central Illinois Healthy Community Alliance around the recently announced settlement to close the E. D. Edwards coal plant just outside Peoria. As part of that agreement, the plant’s owner, Vistra Energy, will invest $8.6 million in workforce development and public health measures.

“The fact that there’s money in the settlement at all to support a transition and public health in this community that was so impacted by this coal plant is tremendously exciting and encouraging,” Kibbey says. “And the fact that it’s not just the lawyers in a room somewhere deciding what they think should be done with the money but an ongoing conversation with members of the community to decide where that money goes, is an important example of the right people being at the table. Edwards can and absolutely should be a model for the way that we think about coal closures.”

On a personal level, Kibbey saw how clean energy job training and development can uplift communities affected by a dying coal industry when his cousin found new work as a wind turbine technician in West Virginia.

“The fact that somebody from our family, from the same hills that we used to dig coal out of, was now up on top of them, getting paid good money as a veteran to build wind turbines, to me is really cool,” he says. “It shows that there is something better on the other side if we do this right. It's not just a mirage or a dream; there really is a clean energy economy that can work.”

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

The Revitalization of This Former Coal Town Starts Now

This Is What a Just Transition Looks Like

Kill the Renewable Energy Industry? The Midwest Says “NO!”