Happy 50th Birthday, EPA

We’ve seen you at your best and, currently, at your absolute worst. But things are looking up for you again—just when we need you the most.

EPA Administrator William D. Ruckelshaus (left) and chair of the Council on Environmental Quality Russel Train (right) look on as President Richard Nixon signs new rules on automobile exhaust smog.

Wow, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency—you’re turning 50! Amazing. It seems like only yesterday we were watching you learn to walk through the morass of administrative law, rulemaking, and politics that eventually became your stomping ground. Over the decades, we’ve relied on your scientific guidance and sung your praises many times. But you’ve also let us down, and more than once. One thing you’ve shown us: While you’re an indispensable tool for protecting public health and the environment, you’re only as good as the people who run you.

As you begin your journey into the next half century (one that’s shaping up to be quite a doozy), here’s an appreciative—but honest—account of your life so far.

The 1970s: Your Formative Years

You came into the world on December 2, 1970, in Washington, D.C. and not a moment too soon, either: Just the year before, an oil spill dumped three million gallons of thick, black crude onto 35 miles of California coastline, air pollution in our cities was so bad that it was hard for people to breathe in them or even see their skylines, and the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland was so contaminated with flammable industrial waste that it actually caught fire. We were all so excited to add you to our federal agency family! In the words of your first administrator, William Ruckelshaus, you never would have been born “had it not been for public demand. That I am absolutely certain of. Public opinion remains absolutely essential for anything to be done on behalf of the environment.”

What an active, energetic baby you were! At barely a month old you were exercising your newfound authority to enforce the Clean Air Act by setting standards for air pollutants and auto emissions and by requiring states to create their own air quality improvement plans. Before long you were also fighting to get lead out of paint and gasoline, banning DDT in pesticides, and working to eliminate chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) from aerosol cans in an effort that would eventually help save the ozone layer.

Oh, and you would get so angry whenever you saw people treating water badly. Remember when dumping raw sewage into rivers was common practice? You aggressively pushed cities and states to build wastewater treatment facilities instead. (Sheesh, seems like common sense now . . .) You created the first national limits for what industries could dump in our waters, too, and you improved the quality of the public water supply under the aegis of the Safe Drinking Water Act. That’s just the kind of kid you were—always trying to help!

The 1980s: Your Turbulent Teens

When you were 10, you reacted to the Love Canal disaster in western New York, where toxic waste had been leaching into the homes and destroying the health of hundreds of families, by creating a new nationwide mechanism for cleaning up industrial sites under the new Superfund law. That pretty much set the tone for how you’d spend much of your teen years: working to get toxic chemicals out of our land, water, and communities. Citing your authority under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, you began to ramp up—awkwardly, and not without political complications—law enforcement around the storage and disposal of hazardous waste “from cradle to grave.” Later you made companies divulge the toxic chemicals they were using or producing at their sites via your Toxics Release Inventory. This publicly available database, an important part of the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act of 1986, continues to equip people with the information they need to fight back against industrial polluters.

Soon after, you became the lead agency for developing a national climate change plan, and later you created the Energy Star®️ program to encourage the use of energy-efficient appliances. But like any teenager, you also made some really bad choices, too often allowing yourself to be swayed by the negative influences in your life. When everyone was learning about Alar, a growth regulator sprayed on apples and other food crops, you acted at first as if you were going to do something about this chemical, which is known to be harmful to human health, especially children’s health. But then you flaked out, for reasons that may have had a lot to do with those industry-coddling, anti-regulation types you were hanging out with over at Ronnie Reagan’s house. One of your administrators during that era, Anne Gorsuch, took special relish in weakening rules that you had spent years building up and enforcing. Gorsuch liked to hold closed-door meetings with polluters, whom she would allow to “self-regulate” and blow off their compliance deadlines. At one point, she even boasted about how many clean-water protections she had done away with. (Gotta be honest here: We were all happy when the two of you broke up, ugly though it was.)

Eventually, you did the right thing on Alar, but only after being publicly pressured to do so. The whole episode was a sobering reminder that while you yourself aren’t political, you’re always vulnerable to politicization.

1990–2010: Coming Into Your Own . . . and Then Losing Your Way

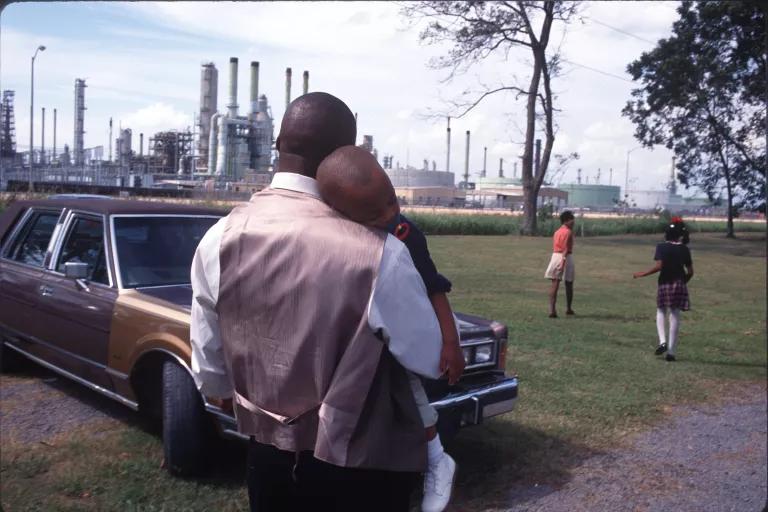

You entered your twenties with a burst of energy: adding new amendments to the Clean Air Act, banning the dumping of sewage sludge into coastal waters, and bolstering your environmental enforcement and compliance programs. Then, mid decade, you revisited an issue that you had worked so hard on in your early teens: protecting communities from industrial toxins. In 1994 you announced one of your biggest projects up to that point, a chemical manufacturing rule aimed at reducing the air pollutants emitted by chemical plants by almost 90 percent in three years. In 1995 you turned your attention to brownfields—abandoned industrial sites, often contaminated, and disproportionately found in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. You launched a grants program to help turn them into assets by cleaning them up and repurposing them as housing, green space, or commercial space. You also greatly expanded the list of toxic chemicals requiring public disclosure under the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act.

But you fell back into your old, dissolute ways at the turn of the century. Under the administration of President George W. Bush, you tried to weaken protections against arsenic in tap water, of all things, and you set standards for soot, smog, and lead pollution that were way lower than what your own scientists recommended. You failed to set a national drinking-water safety standard for perchlorate, a component found in rocket fuel that can cause brain damage in fetuses and children and thyroid damage in adults. And as governments around the world were beginning to address climate change at the policy level, it literally took a Supreme Court ruling for you to start regulating carbon dioxide emissions from motor vehicles. Among those of us who cared about you, it seemed like you couldn’t get any lower. (Little did we know then how far you were from hitting rock bottom.)

2010–2020: A High Climb, Then a Hard Fall

Then, right before you turned 40, Americans elected Barack Obama to the White House—and you finally snapped out of your slump and began attacking the country’s environmental problems with renewed passion and vigor. You connected the dots between climate action, environmental justice, technological advancement, and economic growth. You officially declared that carbon dioxide emissions pose a danger to public health, which opened the door to a host of policies designed to curtail greenhouse gases and mitigate the warming of the planet. You set new standards for tailpipe emissions, working with states and automakers to dramatically increase fuel efficiency. And you enacted stringent new carbon pollution standards for power plants, not just as a means of slashing pollution but as a way to strengthen the burgeoning renewables sector and hasten the transition to clean energy—the first step in what later came to be known as the Clean Power Plan.

Once you got started, there was no stopping you. You clarified the authority of the Clean Water Act with a Clean Water Rule that would protect hundreds of thousands of miles of streams and tens of millions of acres of wetlands across the country. You fought to implement the Clean Power Plan, which would have every state set its own targets for slashing carbon emissions from electricity generation and would collectively shrink the country’s carbon footprint by nearly a third by 2030. When President Obama signed the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015—along with nearly 200 nations—you were right there by his side, making it clear that you were going to play a major role in keeping our promises to the world and ourselves.

And then . . . well, we all know what happened next. Look, it’s not uncommon for people in their mid 40s to experience an existential crisis—to lose their bearings and engage in reckless, even destructive, behavior. But wow, yours was one for the record books. When Donald Trump became president in 2017, you went into a nihilistic tailspin. You rolled back more than 100 environmental protections and foreclosed on climate action. You stopped showing up for work. You started palling around with the fossil-fuel crowd and the Big Ag crowd. You listened to science-class dropouts while bullying your own researchers and scrubbing climate data from your website. You tried to get rid of your Environmental Justice office as well as your children’s health program. You didn’t merely turn a blind eye to corporate polluters; you aided and abetted them. Back-to-back administrators Scott Pruitt and Andrew Wheeler exploited you, exhausted you, and turned you into a dark parody of what you were meant to be. Meanwhile, the people who depended on you watched your unraveling in horror and wondered if you would ever come back.

2021 and Beyond: A Chance for Redemption

Now, on your 50th birthday, you’re still behaving like there’s no tomorrow. But in a little more than a month, you’re in for a wake-up call. There’ll be a new boss in town, and it doesn’t seem like your pro-polluter, anti-climate science attitude is going to fly anymore. Which is a good thing, given how much work you have to do (and—ahem—undo). But don’t worry, you still have a staff of dedicated scientists and experts to support your next transition, and you can be certain they’re eager to shake off the past four years and to get back to the mission of protecting public health and the environment. Though we don’t yet know who’ll take your helm in the incoming Joe Biden administration, we can safely assume it will be someone who’s ready to go hard on climate change, environmental justice, and so many other crucial issues that you’ve neglected for too long.

We’ll just come right out and say it: You aren’t perfect, but we need you. We need you to make sure our air and water stay clean. We need you to enforce the rules meant to keep people—especially the most vulnerable among us—safe. We need you to lead the transition from dirty fossil fuels to clean energy, creating healthier communities and millions of jobs in the process. We need you to craft rules and policies that will help us mitigate and survive the climate crisis.

So: Happy birthday, EPA! You’re such an important part of our lives that sometimes we forget just how much you’ve done for the country since 1970. But yes, you could do a lot more—and we’re going to keep pushing you to be the best agency you can be. So blow out those smoking candles already, and get ready to go back to work. For us.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

What Is the Air Quality Index?

How to Make an Effective Public Comment

How to Become a Community Scientist