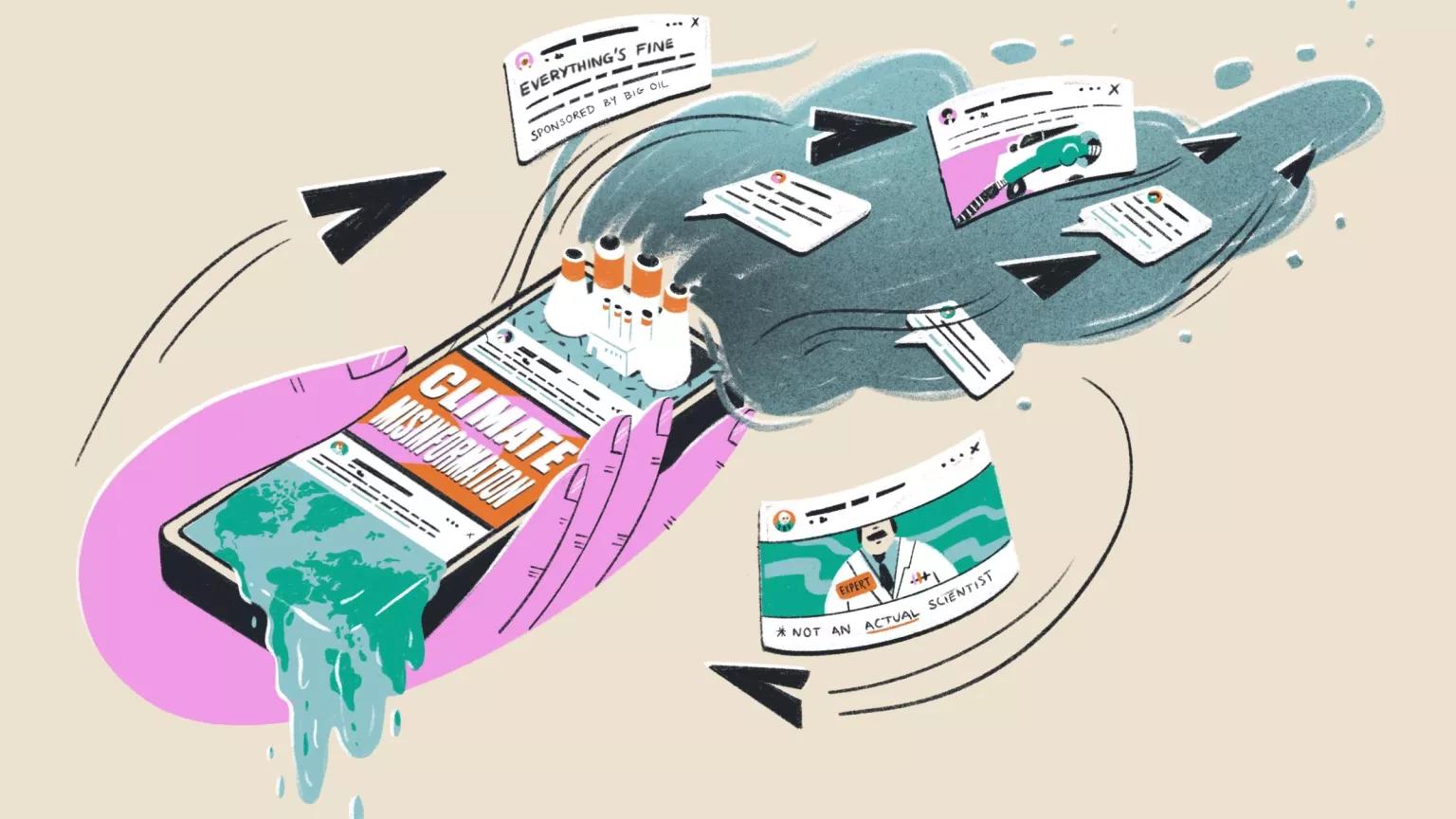

How to Spot—and Help Stop—Climate Misinformation

The online spread of false claims about climate change is an existential threat.

Tara Jacoby for NRDC

For the first time in its history, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has named the spread of climate misinformation as an obstruction to climate action, particularly in the United States.

In fact, a recent report by advocacy group Stop Funding Heat found that climate misinformation—false information that’s spread either by mistake or with the intent to mislead—gets viewed up to 1.36 million times every day on Facebook alone. And the problem appears to be getting worse on nearly every social platform.

But separating climate fact from climate fiction isn’t always easy.

Climate misinformation can look like your cousin sharing a conspiracy-laden blog post on Facebook, thinking it’s accurate. But it can also come from a conservative think tank publishing an intentionally deceptive (and fossil fuel–sponsored) report about the cost of solar energy. In both cases, the climate falsehoods breed confusion, polarize, and can ultimately have the power to influence government policies.

“We need climate information and climate commitments to be real if we’re going to have any hope of stopping the worst of global warming,” says Sujatha Bergen, NRDC health campaigns director. “Climate misinformation is distracting at best. At worst, we end up not taking the actions we desperately need to take.”

Here are some tips for how to recognize climate misinformation—and help stop its spread.

First things first: Know that climate misinformation is shape-shifting

A decade ago, spreaders of climate misinformation were more likely to outright deny climate change, intentionally rejecting the science of global warming altogether. Today, that’s not usually the case.

“The biggest shift has been the gradual transition from science denial to solutions denial,” says John Cook, a cognitive scientist at the Monash Climate Change Communication Research Hub in Melbourne, Australia, whose research focuses on preventing climate misinformation. This version of denial still seeks to undermine and potentially delay climate action, but its false arguments are more subtle. They peddle lies that say climate policies are harmful for the economy or that you can’t trust climate scientists.

Climate misinformation can also take the form of greenwashed promises, which cloak polluting behavior in environmentally friendly language—think of misnomers like “clean coal”—and can be spread via online ads and social posts. Fossil fuel companies, for example, publicly set net-zero targets that give the appearance of dealing with climate change but, when scrutinized, show that these companies have taken negligible steps to reduce fossil fuel production, the single-greatest contributor to planet-warming emissions.

Learn to recognize misinformation tactics.

One of the most effective ways to counter climate misinformation, Cook says, is to understand the five primary techniques used to spread it. This awareness allows you to “pre-bunk” misinformation—aka, inoculate yourself against it before coming across it. You can remember the techniques, as originally defined by Mark Hoofnagle and further developed by Cook, with the handy mnemonic device FLICC.

- False expertise: Presenting an unqualified person or institution as a source of credible information.

- Logical fallacies: Arguments where the conclusions don’t logically follow from the premises.

- Impossible expectations: Demanding unrealistic standards of proof before acting on the science.

- Conspiracy theories: Proposing that a secret plan exists to implement a nefarious scheme, such as hiding a truth.

- Cherry-picking data: Carefully selecting data that appear to confirm one position while ignoring other data that contradicts that position.

You can practice spotting these techniques using Cook’s gamified app, Cranky Uncle. His research shows that pre-bunking works, no matter a person’s political affiliation. “What the research tells us is that people don’t like being misled, regardless of where they sit on the political spectrum,” Cook says.

Be a cautious consumer.

If a piece of content doesn’t clearly reflect a misinformation tactic, but you’re concerned, there are a few general ways to check it.

- Vet the source. Look at who’s doing the talking. If it's a news story, then go back to its original site. Does the publication have signs of legitimacy, like an “about” page and clear contact information? Do other trusted news sources refer to it? And if you’re reading commentary from an individual’s social media account or blog, question their climate expertise. A simple Google search for the author is a good start. “Our general rule of thumb is that having published scientific research on a topic is the gold standard of expertise,” Cook says. Still unsure? Check their claim against fact-checking sites like Climate Feedback or Snopes. You can do the same for images using this and for video using this.

- Develop a mixed-news diet. Take the time to see how various trusted news outlets are reporting on the same issue. Consuming climate information from a variety of sources means that misinformation is more likely to be drowned out.

- Check links. It’s now second nature to highlight a statistic in a story by linking out to its source. But don’t just assume the link itself is all the proof you need that something is a fact. Click through to find out.

Stop the actual spread.

Aside from learning to better spot climate misinformation, you can also help quash it.

- Pause before you share. Break the habit of reflexively sharing without properly vetting. Much misinformation is unintentionally spread, but that doesn’t make its effects less harmful.

- Debunk with a “truth sandwich.” If you’re going to correct climate misinformation, start by clearly stating the truth. Then quickly address the falsehood and fact-check it. Finally, restate the correct information. This avoids giving the misinformation too much space—and makes the reader’s final takeaway the right one.

- Report climate misinformation on social media. Despite their past failures to adequately address this issue, social media companies have shown—with topics such as COVID-19 and the presidential election—that they can be proactive about misinformation when sufficiently motivated. Social media platforms also have a range of tools they can and should use to systematically combat climate misinformation. You can do your part by reporting it when you see it. This guide, broken down by platform, shows you how.

You can also advocate for stronger policies by reaching out to your political representatives. And when you come across misinformation in your own feed, do something. Because, honestly, the stakes couldn’t be higher. “If the public remains polarized over policies and solutions, then it’s going to be impossible to get things through Congress,” Cook says. “Misinformation continues to be a big problem—and we ignore it at our own peril.”

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Electric vs. Gas Cars: Is It Cheaper to Drive an EV?

Liquefied Natural Gas 101

The Uinta Basin Railway Would Be a Bigger Carbon Bomb Than Willow