Needing Water, Georgia Stirs Up a 200-Year-Old Dispute With Its Northern Neighbor

As droughts parch the Southeast, interstate squabbles heat up over the Tennessee River (and the Chattahoochee . . . and the Flint . . . and the Apalachicola).

The Tennessee River in Chattanooga, Tennessee

TDP Photography/Alamy Stock Photo

In 1818, a government surveyor named James Carmack bumbled Tennessee’s southern border. Instead of drawing a line along the 35th parallel, as designated by Congress, he put the border a mile south, in Georgia. The blunder kicked off a conflict that has spanned two centuries, with many in the Peach State wanting to reclaim the land—and especially the freshwater that comes with it.

Over the past two years, the Georgia General Assembly passed two resolutions in an attempt to negotiate the 51-mile-long “true border” with Tennessee. What Georgia’s lawmakers really want is a pipeline into the Tennessee River, which runs through Chattanooga north of the border before dipping down into Alabama, narrowly missing Georgia (at least according to Carmack’s survey). The most recent resolution argued that since some of the river’s tributaries originate in six Georgia counties, the water is being stolen.

Tennessee has never taken seriously Georgia’s requests to negotiate. In 2008, to mock (or perhaps to fuel) the ongoing discord, Chattanooga’s mayor sent a truckload of bottled water to Atlanta instead of showing up at the bargaining table. In fact, the Volunteer State has punted on the issue since 1887, while Georgia’s legislature has voted to reopen negotiations dozens of times. Some consider the recent proposal to build a 130-mile pipeline—which would have to run over Georgia’s Lookout Mountain pipeline before stretching to Atlanta—a logistical nightmare that would cost tens of millions of dollars.

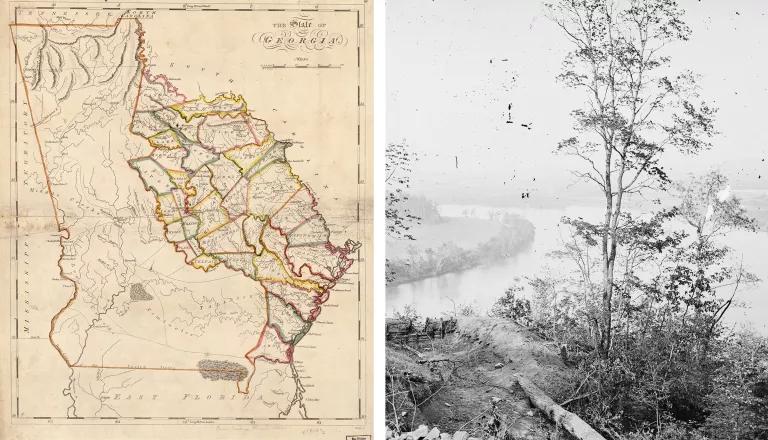

From left: An 1818 map shows the Georgia Tennessee border drawn along the 35th parallel; a view of the Tennessee River from Lookout Mountain in Chattanooga

Library of Congress

Environmental groups have also shown little support for the pipeline proposal, and due to Tennessee’s lack of interest, in May 2019 Georgia Governor Brian Kemp vetoed the resolution suggesting it. One thing, however, is certain: Georgia is facing a water shortage.

A Shriveling Peach

With its population quickly nearing a half million people, Atlanta is the country’s third-fastest-growing city. Atlanta’s Fulton County is expected to need more than 300 million gallons of water per day by 2035. The city is dependent on surface water, which makes it extra sensitive to drought. And “here in Georgia, climate change looks like drought,” says Brionte McCorkle, director of Georgia Conservation Voters.

This past fall kicked off with “flash droughts,” a new term for the rapid onset of low-rainfall, in 14 southern states. The U.S. Drought Monitor categorized large swaths of northern Georgia as suffering extreme drought, characterized by widespread water shortages and restrictions along with major agricultural losses. Around the same time, Atlanta broke a heat record by having its 91st day of the year with temperatures topping 90 degrees Fahrenheit. The city’s average number of days this hot is 51, but according to the Union of Concerned Scientists, even if bold steps are taken across the world to uphold the Paris climate agreement, Atlanta will likely still see that 90-degree-day average skyrocket to 97 days by the end of the century.

Drought conditions in Atlanta's reservoir Lake Lanier in Buford, Georgia, in late 2007

Chris Rank/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Atlanta currently gets 70 percent of its water from Lake Lanier, which lies about 50 miles to the northeast. The lake was created in the 1950s when the Buford Dam was built to wall off a section of the Chattahoochee River. Thanks to this year’s drought, the lake’s water level is three feet below average. This might not seem like much, but it has huge consequences for the water supplies of Georgia, Alabama, and Florida. The Chattahoochee River Basin extends across all three states, and any further usage restrictions on the basin would add fuel to the “tri-state water wars,” a term describing the two decades of legal battles over the Chattahoochee, Flint, and Apalachicola rivers.

For instance, this coming November, the U. S. Supreme Court is expected to rule on a water wars case that could potentially cap Georgia’s withdrawals from the Chattahoochee at current levels. Florida—which is also facing severe freshwater shortages and has one of the fastest-growing populations in the country—blames Georgia’s overuse of the Chattahoochee River Basin for the collapse of its oyster industry.

The Power of Conservation

According to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, in coming years the Southeast will likely experience heat waves and droughts with increasing frequency and duration (along with wildfires and coastal flooding). But the report, released in late 2018, also highlights Atlanta’s progress in improving water efficiency by such means as residential retrofits and the repair of leaking fire hydrants and water mains. The city of Atlanta’s Climate Action Plan implemented water management strategies in 2015 that have reduced water consumption citywide. There has been statewide progress as well: In 2000, the average Georgian used around 150 gallons of water per day. By 2016, that per capita water usage had dropped by about 40 gallons.

A residential development near Atlanta

Formulanone via Flickr

“If you look at water conservation in metro Atlanta, we lose less water than we did 10 years ago and we’ve cut just about every way we can,” says Georgia Representative Marc Morris. But even with improved efficiency, he worries about the demands of a growing city. “Water’s one of those things that you’ve got to have, and we need an additional source,” Morris says.

Tonya Bonitatibus, director of Savannah Riverkeeper, points out that while talk of water conservation in Georgia tends to center on residential use, the focus needs to shift to industry: “Your biggest obstacles,” she says, referring to outsize water consumption by the energy and agricultural industries, “are by far your biggest returns.” By 2050, the state’s farms are expected to increase their water draws by more than 50 percent. And water-guzzling energy producers like coal and nuclear plants account for almost half of Georgia’s total water demand.

About a quarter of Georgia’s electric supply comes from coal-burning power plants, which use large amounts of water to produce steam for their turbines. As part of its plan to become a “low to no”–carbon generation utility by 2050, Southern Company (Georgia Power’s parent company) is phasing out coal. The utility announced plans earlier this year to shutter two of its coal-burning units, one at Plant McIntosh in Rincon and the other at Plant Hammond near Rome. Now Georgia has only three coal-fired power plants in operation.

Georgia Power also wants to add a gigawatt of renewable energy to its portfolio by 2050. The company has already been adding solar farms to its mix of energy sources—a source that, like wind turbines, requires no water to run. For its part, in 2018, Atlanta became the first city in the South to pledge to get 100 percent of its electricity from renewables by 2035. While solar accounted for less than 3 percent of Georgia Power’s energy generation last year, that contribution could, by one measure, jump to 20 percent within five years.

Southern Company’s plans to expand its Vogtle nuclear plant, however, do not bode well for the state’s water supply. Nuclear reactors need a constant supply of water to keep cool and prevent meltdowns. Georgia’s two nuclear plants, Hatch and Vogtle, currently generate 20 percent of the state’s electricity, but the plants evaporate vast quantities of water. The resulting low water levels in the rivers the plants draw from, says Bonitatibus, lead to reduced oxygen levels and more concentrated pollutants in the waterways.

Now, two more nuclear units in Georgia may be on the way. (These additions to the Vogtle plant are the only new nuclear reactors currently under construction in the United States—and they’re not going well. Construction is five years behind schedule and $14 billion over budget.) If ever completed, Vogtle’s new reactors would consume enough water for more than a million Georgians each day and double the daily water withdrawals from the Savannah River to 90 million gallons.

The Georgia Water Stewardship Act, passed in 2010, requires all utilities to conduct annual water audits in an attempt to account for and improve water loss due to infrastructure. “There’s a lot of good law and policy in the state of Georgia when it comes to water use,” says Chris Manganiello, water policy director for Chattahoochee Riverkeepers, “but the downside is the lack of implementation and enforcement.”

A 2019 report he authored suggests that Atlanta could save 14 million to 22 million gallons of water per day through updated state plumbing codes, audits for commercial water users, updates to the Water Stewardship Act, and better enforcement. The stance of the Riverkeepers is that Atlanta already has enough water and just needs to keep improving its conservation of it.

Pipe Dreams?

Despite all the recent (and not-so-recent) setbacks, some Georgians still have their eyes on the river flowing through their northern borderlands. “If we collected one-third of the water that flows out of Georgia and into the Tennessee River, it would solve the water wars,” says Morris, the recent “true border” resolution’s main sponsor, whose district includes Lake Lanier. He estimates that with a pipeline into Tennessee, his state could recapture 500 million gallons of water a day for its residents.

Morris says the only other solution would be to build a desalination plant on the Atlantic coast and pump its output some 250 miles northwest to Atlanta. But that, he says, would produce “the most expensive gallon of water” Georgia has ever seen.

Environmentalists, however, see other options. Manganiello considers the pipeline plan a flashy idea but thinks an interbasin transfer like that would be complicated and expensive to build and maintain. Bonitatibus agrees. “They’ve already got their straws all over the place,” she says of the pipeline proposal. “The biggest thing that needs to happen in Georgia is conservation and getting people to use the water that’s available.” Waste not, want not, goes the old proverb, and that principle, plus smarter energy sources, will be essential to calming the water wars—especially as climate change alters the battleground.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

In Planning for Climate Change, Native Americans Draw on the Past

California’s Climate Whiplash

Colorado River Basin Tribes Address a Historic Drought—and Their Water Rights—Head-On