Toxic “Forever Chemicals” Came Between This Farmer, His Cows, and the Air Force

The PFAS-laden firefighting foam used in training exercises at military bases easily slips into groundwater supplies, tainting everything around it.

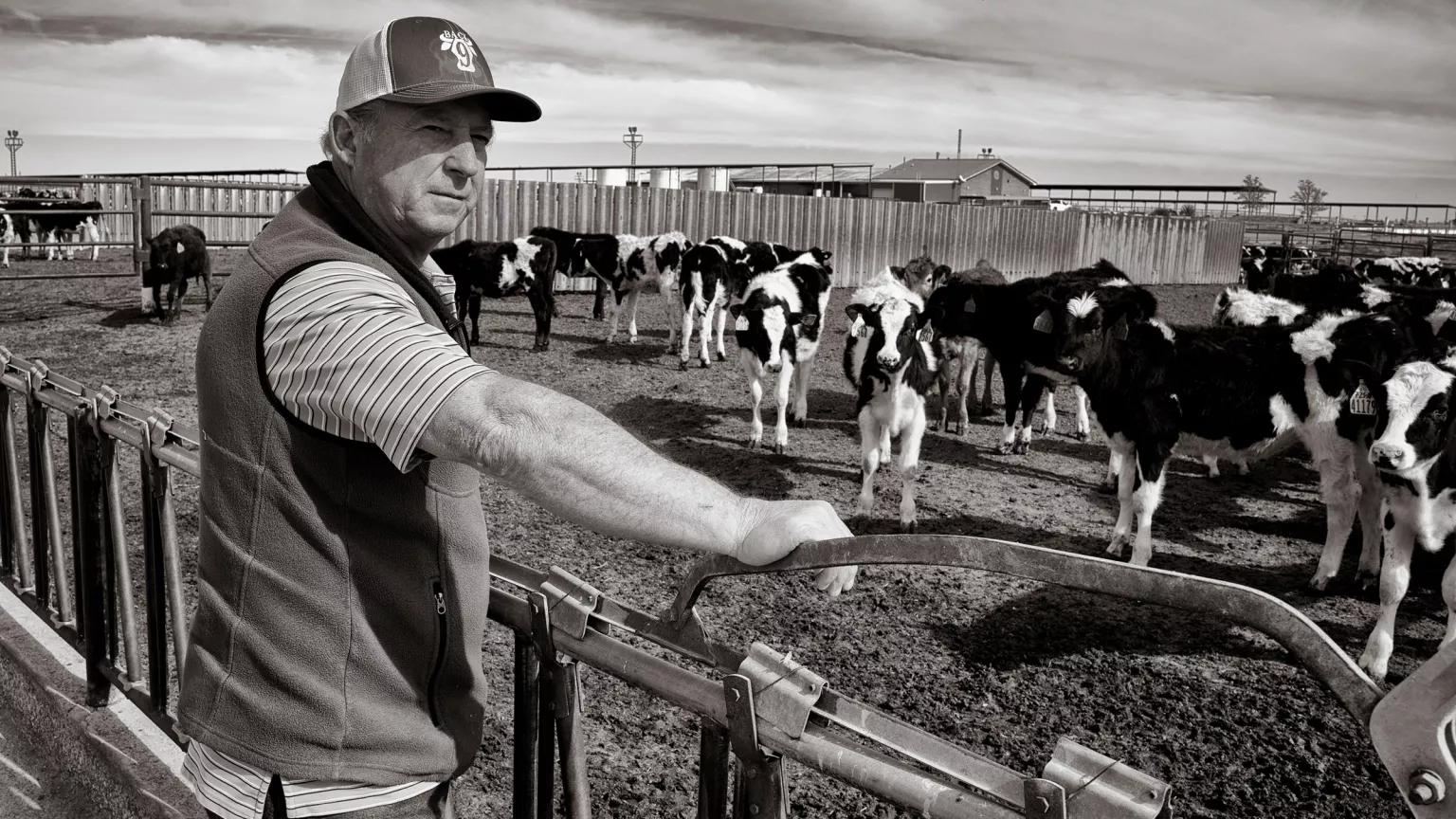

Art Schaap looking over some of the 1,800 cows that once grazed on his farm

Don J. Usner/Searchlight New Mexico

When Art Schaap looks out across his sprawling property, he sees broad, blue skies and 4,000 milking cows. But it’s what he doesn’t see that has ruined him.

In August 2018, the longtime Clovis, New Mexico, dairy farmer was approached by officials from nearby Cannon Air Force Base who asked to test his well water. Those tests revealed sky-high levels of contamination by toxic chemicals called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Commonly known as PFAS, they can have serious health impacts, including immune system deficiencies, low birth weights, and cancer.

Called “forever chemicals” because they never break down, PFAS are found in products ranging from waterproof clothing to Teflon cookware. The chemicals’ prevalence has led to contamination incidents at various facilities around the country, including nearly 1,400 airports, landfills, and manufacturing plants. And because they’re also a key component in firefighting foam used in training exercises at U.S. Air Force installations—where they easily slip into groundwater supplies—military bases have been impacted as well. The Pentagon has admitted that there are more than 400 military bases across the country with known or suspected PFAS contamination. (Northeastern University and the Environmental Working Group have produced a map of many of these sites.) Contaminated drinking water and groundwater have been confirmed at 167 of them.

Some 40 wells dotting Schaap’s 3,600-acre property draw groundwater from the already stressed Ogallala Aquifer, and the Air Force’s testing showed that more than a dozen of them were contaminated by PFAS. At least one well had levels 170 times higher than the safety standards issued by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Nor is the Schaap family alone; these chemicals are spreading throughout the huge aquifer, which provides water for eight states from New Mexico to South Dakota.

Schaap at the most contaminated water well, just outside Cannon Air Force Base

Don J. Usner/Searchlight New Mexico

Schaap’s cattle were contaminated as well—which meant that he was suddenly out of business. He laid off his 40 employees, began dumping thousands of gallons of milk, and hoped to sell his cows—until he learned that the U.S. Department of Agriculture had warned packing houses not to buy them. Now he’s stuck with tainted milk, sickly livestock, and an operation that once ranked among the nation’s top 25 dairy producers but today is nearly worthless. “Who is going to buy a farm with polluted water, cows that are not worth anything, and a dairy that’s not worth anything?” says the 55-year-old. “I told my wife I wanted to retire, but I didn’t want to retire this way.”

At least now Schaap knows why his cows’ milk production has been dropping for years, costing him roughly $50 million in lost revenue over the past two decades.

Schaap stopped breeding and raising calves when PFAS was detected in his cows’ milk.

Don J. Usner/Searchlight New Mexico

Dereliction of Duty

Since sharing its findings two summers ago, the Air Force has done little more than to provide the Schaap family with bottled drinking water. The U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) has refused to install multimillion-dollar filters that would make their wells usable again or to compensate them for their losses. With few remaining options, in November the Schaaps sued the DOD, the Air Force, and PFAS manufacturers, including 3M.

The Schaaps’ case followed a lawsuit filed by the State of New Mexico last March, aimed at compelling the Air Force to clean up its mess near Cannon and at Holloman Air Force Base 250 miles to the southwest. Sampling around Holloman—where PFAS chemicals have been used since at least the 1970s—shows contamination levels dozens of times higher than federal safety standards. At least five PFAS release sites have been identified on the base, raising concerns among the 31,000 residents of the nearby city of Alamogordo and prompting state officials to demand closure of Holloman’s popular lake.

An Air Force spokesman, Major Robert Leese, declined to comment on the pending litigation.

Chris Atencio, an attorney with the New Mexico Environment Department, says the state tried various means to get the Air Force to act, including filing a notice that the military had violated New Mexico’s water quality regulations. But federal lawyers argued that the U.S. government enjoys “sovereign immunity” from being sued by states without its consent, a concept challenged by the lawsuit. As this fight slogs on through the courts, New Mexico has requested a preliminary injunction that would force the military to start analyzing the extent of its PFAS pollution. “We think this threat is serious enough that it can’t wait for several years to be addressed,” Atencio says.

The challenge to federal authority is being closely watched across the country, with good reason: According to Charles de Saillan, a staff attorney with the New Mexico Environmental Law Center, sovereign immunity should not impede states from suing when they’re only exercising powers granted to them by the federal government. In this case, the federal Resource Conservation and Recovery Act—a framework the EPA uses to manage hazardous and nonhazardous solid waste—also lets that agency delegate power to the states. In other words, the feds can’t have it both ways. “We think they’re wrong,” de Saillan says of the federal government’s position. “The Air Force is dragging its feet. My view is that they need to spend the money here in New Mexico to get this cleaned up quickly. If they wait longer, there is a possibility for contamination to spread, and that could cost them significantly more money.”

There are certainly plenty of water treatment options available for removing PFAS chemicals from drinking supplies, such as reverse osmosis and carbon filtration. Even more critical is curbing the manufacture of PFAS altogether, say advocates—which requires broader awareness of just how dangerous these toxic chemicals can be. Anna Reade, an NRDC staff scientist, says the public is currently on the frontlines of this battle. “There is a market push as more people realize the health costs of using these chemicals,” she notes. In response, some retailers, including Lowe’s and Home Depot, have recently stopped selling carpets containing PFAS in the United States and Canada. “But the question is, what will motivate some of these larger chemical companies to move away from using PFAS?” Reade asks.

Rising legal costs may be one motivator. In coming years, according to some estimates, the industry’s PFAS manufacturers may have to pay upwards of $40 billion as a result of the widespread contamination they have caused and in response to the lawsuits of plaintiffs like Art Schaap, among others.

A warning sign on the Cannon Air Base fence that borders Schaap’s farm

Don J. Usner/Searchlight New Mexico

Lawmakers and the Chemical Industry Weigh In

Whatever the costs, lobbyists for PFAS manufacturers displayed their enduring clout on Capitol Hill recently as Congress debated the National Defense Authorization Act for 2020. The annual funding measure contained a number of provisions aimed at cleaning up PFAS contamination, including listing these chemicals as hazardous substances under EPA’s Superfund law. That classification would have enabled the federal government to hold major PFAS polluters accountable for hazardous releases and provided resources to help impacted communities clean up.

But while the House voted to keep the Superfund provision in the bill, industry lobbyists persuaded the Senate to defeat the measure, using scare tactics such as claiming that municipalities could be held liable for the huge costs of cleanup. According to Erik Olson, senior strategic director for health and food at NRDC, “the big chemical industry created a smokescreen to raise uncertainty about what it would mean to cover PFAS under Superfund. But in fact, there are all sorts of chemicals out there that are covered by Superfund that have not resulted in municipalities having to run around paying for cleanup.”

In an email response to an inquiry, American Chemistry Council spokesman Tom Flanagin disputed Olson’s characterization. The trade group and its members “are committed to working with lawmakers to identify ways to address potential concerns with PFAS chemistries,” he wrote. “For this reason, the chemical industry supports a comprehensive approach with clear timelines for managing specific substances, including measures to prioritize, evaluate, regulate, innovate, monitor, and advance best practices.”

On the bright side, the final Defense Authorization bill does include several key breakthroughs. It mandates that the DOD stop using PFAS-laden foam at military installations by 2024 and calls on federal agencies and many drinking water utilities to subject the chemicals to greater and more transparent monitoring. It also requires the DOD to join in cooperative agreements with affected communities and allows it to buy certain contaminated land and relocate people living there.

Those provisions were championed by New Mexico’s congressional members, including Senator Tom Udall. In a statement, Udall called himself “proud that the New Mexico delegation secured this important measure to provide deserved relief to the families, business owners, farmers, service members, and communities who have suffered from exposure to PFAS chemicals in New Mexico.” He added, “Federal agencies have dragged their feet for too long, but this bill will finally push them into action."

For his part, Schaap is focused squarely on the chance that the DOD might buy his land and move his family. “That is my first option,” he says. “I don’t want to farm on top of pollution. We’ve been on this place almost 30 years and built a beautiful home. And they basically ruined it.”

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Biodiversity 101

If You Care About Climate Change, Then You Care About the Farm Bill

Greenhouse Effect 101