Two different very different studies were released this week. But if you look at them together, they paint a potentially alarming picture for both pollinators, like bees and butterflies, and the native grasslands and prairies they depend on.

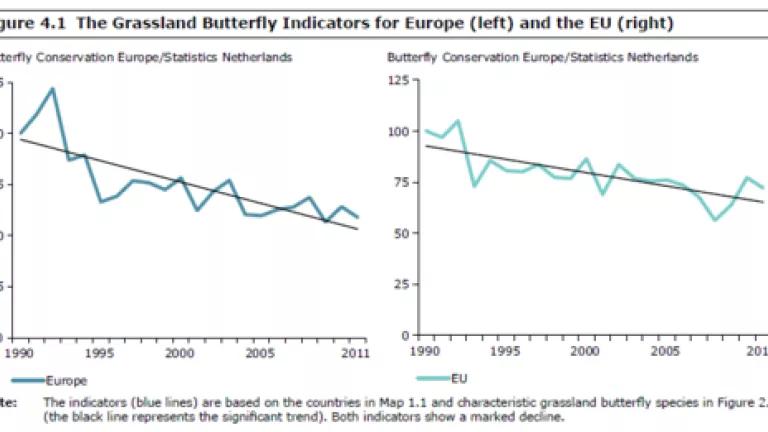

In the first study, the European Environment Agency presented the results from two decades of monitoring butterfly populations across Europe. They show that, “compared to 1990, the European populations of the 17 indicator species have declined by, on average, almost 50%.”

The report lays the blame for this decline at the feet of intensifying

agricultural activities on easy to cultivate land and, ironically, the abandonment of cultivated grasslands, used for livestock grazing and growing hay, on marginal lands. Both activities end up destroying butterfly habitat, either through the creation of monocultures and the use of pesticides or the reversion of habitat to scrub and forest.

But what if the decline of butterflies also causes the decline of grasslands?

That’s the implication of a different study, conducted in Colorado, where scientist looked at the reproductive success of plants on plots of land in subalpine meadows containing ten species of native bumblebees. Then they removed one of those species. Computer models had suggested that “plant communities will be resilient to losing many or even most of the pollinator species in an ecosystem” as the remaining bees take up the slack. But that’s not what scientists found at all; instead they reported that removing

even a single bee species reduced wildflower seed production a third. Why? Because a competition decreased bees stopped specializing in “their” flower and began moving more between different species of flowers which, if you happen to be a flower, does you no good whatsoever. This decline of “floral fidelity” was dramatic -- 78% -- and resulted in lower reproductive success by the plants.

Does the same mechanism come into play for butterflies? I don’t know. The studies were of different species, in different ecosystems, and on different continents. But butterflies, like bees, are important pollinators of flowering plants so I don’t think that possibility can be dismissed. The result would be a potentially vicious cycle: plant decline begetting pollinator decline which, in turn, causes further plant decline. At the very least, both studies shine a harsh light on decline of animals that we take for granted at our peril.