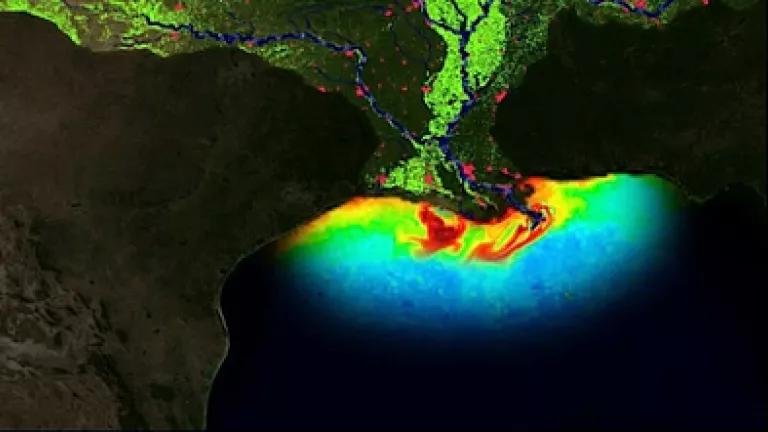

The popular legend is that Chicago’s jazz tradition arose from a migration of musicians from New Orleans up the Mississippi River in the 19th century. It seems Chicago is now returning scat to New Orleans back down the Mississippi, but I don’t mean the vocal kind. The Chicago area’s sewage has been found to be the biggest single contributor to the “Dead Zone” that has emerged in the Gulf of Mexico at the mouth of the Mississippi River – an area larger than the State of Connect

icut where the oxygen levels in the water are so law that it can’t support life. The sewage contains phosphorus, a pollutant that acts like turbo-charged fertilizer fueling the growth of oxygen-depleting algae in the Dead Zone and elsewhere.

A problem of that magnitude can’t be turned around overnight, but NRDC and its partner organizations are doing everything we can to make a start. This week, we are filing two lawsuits against US EPA aimed at compelling it to use its authority and resources – as the Clean Water Act requires – to cut down on the phosphorus in treated sewage, and to numerically limit the amount of phosphorus in rivers and streams. These lawsuits follow the Clean Water Act suit filed last year by NRDC, Sierra Club, and Prairie Rivers Network seeking to compel the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District (MWRD), Chicagoland’s sewage treatment authority, to limit its phosphorus discharges to waters upstream of the Mississippi.

Although very different from one another, all three of our lawsuits seek in some manner to compel government agencies to stop ignoring the phosphorus problem in the Mississippi (and elsewhere) and do their job. The two suits filed this week against US EPA have a national focus. The first simply seeks an answer from US EPA to our concerns. NRDC and its partner organizations filed a petition in 2007 asking US EPA to comply with the Clean Water Act requirement that it update its sewage treatment regulations to reflect what current technology can do to remove phosphorus – not what technology could do in 1985, which was the last time the agency updated its regulations. The petition, unfortunately, has been met with deafening silence, and the law entitles us to an answer. The second suit challenges the really poor – and unlawful – reason US EPA gave us for denying the other phosphorus-related petition we filed. That petition asked US EPA to acknowledge the obvious, which is that current state regulations are not doing enough to control algae-fueling pollution and prevent the Dead Zone, and to set numeric limits on such pollutants. The answer we got from US EPA was not that there isn’t a problem – because there obviously is – but that the Agency wants to continue to leave the problem for the states to solve, despite the Connecticut-sized evidence in the Gulf that this strategy has failed.

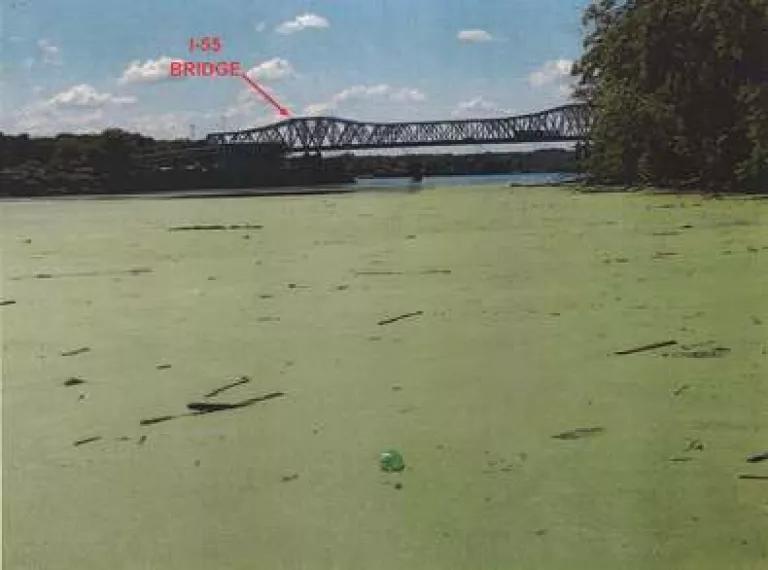

Last year’s suit against MWRD (which remains pending) called out the District’s violation of its permits prohibiting discharges that cause of contribute to excessive growt

h of algae in Illinois waterways. MWRD is discharging substantial amounts of phosphorus 24/7 from its three large treatment plants on the Chicago River system, and not far downstream there are chronic mats of algae – like this one near the I-55 bridge on the Lower Des Plaines River.

Although the suit against MWRD is more locally-focused than the two lawsuits against USEPA filed this week, MWRD’s pollution is clearly part of the larger national problem. The phosphorus discharged by MWRD’s plants travels all the way down the Lower Des Plaines into the Illinois River, and from there to the Mississippi River and on down to the Gulf. As noted above, research has shown that sewage from the Chicago watershed – which is heavily dominated by MWRD’s treatment plant effluent – was determined by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in 2009 to be the largest single contributor of phosphorus and nitrogen, another algae-fueling pollutant, to the Dead Zone.

Of course, the Dead Zone is a death by a thousand cuts. The USGS study identified 150 top-contributing watersheds. Much of the nitrogen and phosphorus finding its way down the Mississippi River to Gulf comes from agriculture, which makes heavy use of nitrogen and phosphorus as fertilizer. But we have to start somewhere, and the largest single contributor to the Dead Zone seemed like a good place to start. And asking a court to get US EPA to do its job, we think, is a good place to go from there.

Dead Zone image: NOAA Environmental Visualization Laboratory