This blog was co-authored by Liz Barratt-Brown, Senior Advisor, NRDC.

Half a year after the president’s rejection, many of the arguments for expansion have been tempered not only by the realities of long term lower oil prices, but by the Keystone XL debate itself. No longer is Canada’s leadership making sweeping statements about being an “energy superpower”. Instead, climate change has risen to a far more important place in the dialogue between the president and his new Canadian counterpart, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

And that is perhaps Keystone XL’s lasting legacy—that after seven years of debate, the central question shifted from an elusive promise of energy security to the magnified dangers of a warming world.

In those seven years, a systematic rebuttal of arguments made by the pipeline’s proponents and a recasting of the pipeline—as our colleagues in Nebraska called it—as all risk and no reward were pivotal to its demise.

At the start of the campaign, winning was an enormous long-shot. The State Department had never turned down a pipeline permit. Hillary Clinton, then Secretary of State, said she was “inclined” to approve the pipeline and the vast majority of nation’s policy experts believed that the pipeline had a near certain chance of approval.

It was clear, almost from the beginning, that we’d have to prevail on five key arguments.

The pipeline would accelerate the extraction of tar sands oil and exacerbate climate change:

We were able over time to show that the pipeline was the lynch pin of the tar sands expansion, in part because its delay actually delayed some very large, multi-billion dollar projects from moving forward, and as oil prices dropped, it became clear that rail—which was argued by the proponents to be the way tar sands would be transported absent the pipeline—was too expensive.

By the time the president made the decision, oil prices were so low that the “unlikely” low oil price scenario in the State Department Environmental Impact Statement (EIS)—where oil prices fell below $75 a barrel—had actually come to be and thus there was no shying away from the fact that the pipeline would cause the equivalent of over 6 million passengers cars worth of carbon pollution every year for at least 50 years.

Our case was bolstered by the statements made by the industry, banks, and investors on the need for the pipeline to keep tar sands oil flowing.

It would NOT increase our energy security by reducing our exposure to the Middle East and Venezuela:

We were able to show with our partners at Oil Change International that the Texas refiners receiving tar sands from Keystone XL—Valero and Saudi Aramco to name two—would export the majority of their refined product internationally using their own reports to shareholders.

And anyone who understands the global oil market knows oil is fungible, with prices and supply controlled by the global market, and that the pipeline would not change that reality (for instance, while we imported over 9 MBPD of oil in 2015, we exported nearly 5 MBPD of oil and refined products).

We were able to drill down on what “energy security” really means in a 21st century context. We worked with retired military generals who made the case that the pipeline would actually decrease our energy security by prolonging our dependence on oil, exacerbating the security risks in climate destabilization and putting our troops at risk.

The pipeline was not safe and posed a particular threat to water and public health:

In July 2010, nearly 1 million gallons of tar sands oil spilled into the Kalamazoo river from an old Enbridge pipeline.

What this spill revealed was that no one knew the impact of pushing bitumen, unrefined tar sands oil, through pipes regulated for conventional oil. No one knew how to clean it up. To this day, over 40 miles of the river are still contaminated by tar sands after over a billion dollars was spent on clean up.

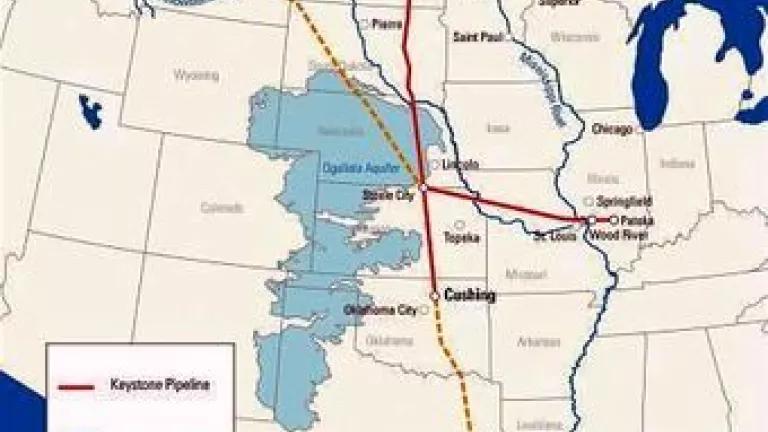

The prospect of a spill happening in one of our largest freshwater aquifers, the Ogallala, was a wake up call. By revealing that tar sands crude behaves differently than conventional oil and highlighting the significant gaps in pipeline safety regulations and industry practices, TransCanada’s 59 “special conditions” began to ring hollow as a safety guarantee.

The risk to land and water were extremely strong and crucial campaigns in Nebraska and South Dakota where rancher and Native American concerns merged powerfully in the Cowboy and Indian Alliance.

n the refinery states, we were able to show that there are more toxic metals and elements associated with refining tar sands oil (petcoke became a big issue in Chicago’s refinery areas and in Texas’ Port Arthur.)

Again time played to our advantage and demonstrated the legitimacy of our concerns. By the time of the president’s decision, there had been numerous spills associated with other tar sands pipelines, petcoke had sickened children as it blew over their playing fields, and whistleblowers revealed that TransCanada had cut corners in building the first Keystone pipeline, Keystone 1, and had otherwise disregarded safety precautions.

The pipeline would NOT lower gas prices or generate lasting employment:

There was plenty of evidence that the pipeline would actually increase gas prices in the Midwest. Because bitumen was landlocked in the Midwest and could only be refined by refineries capable of cracking or coking the oil, it commanded a significantly lower price per barrel than West Texas Intermediate (WTI). If tar sands producers were able to get bitumen to a port, it would command a much higher price. The National Wildlife Federation dug up a quote from the National Energy Board hearings in Canada that oil industry was losing $2-4 billion in profits every year due to this differential—this was at least $2 billion in the pockets of Midwest drivers.

Even though prominent economists weighed in on this early in the campaign, it was so counter-intuitive that it took years before the argument had traction. But ultimately, it helped us defeat the claim that the pipeline would lower gas prices.

Our biggest obstacle was defeating spurious job claims—no one makes the argument better than Comedy Central’s Steven Colbert in which he takes jobs estimates from 35 to 1 million. But much of our work on jobs was underpinned by excellent analysis by Cornell University’s Labor Institute. They were able to show exactly how many jobs were involved in building the pipeline and that if you looked at the broader economic picture, the pipeline was a negative job creator. The reality was that the pipeline would only create about 35 permanent jobs in the US and a few thousand over the course of its construction, about the same amount of construction used in building a subway stop or a small mall. Congress and the president were able to make the case that the infrastructure bill to repair roads and bridges would generate millions of jobs.

The pipeline was not in the National Interest:

Ultimately this was the question the president had to decide in granting the permit. He laid out the tests starting with a speech at Georgetown University in the summer of 2013, where he proposed a climate test for the pipeline.

The Keystone XL pipeline was the first climate tests applied to infrastructure.

On November 6, 2015, the president—flanked by Secretary Kerry and Vice President Biden—rejected the pipeline, finding it not in the national interested. The president methodically reviewed all the tests he had laid out earlier and then referenced the upcoming Paris negotiations. And, important for many in the movement, he spoke about the need to keep “some fossil fuels in the ground rather than burn them and release more dangerous pollution into the sky.” This was a moment that we could barely have fathomed happening years earlier.

Today, six months later, we still face a serious tar sands threat. In spite low oil prices, TransCanada is seeking the approval of Energy East, a massive pipeline that would cross Canada and barge oil out from the Saint Lawrence Seaway. Enbridge has skirted the Presidential Permit and EIS process in expanding the capacity on its Alberta Clipper pipeline with a cockamamie scheme to carry additional oil across the border on a separate 16 mile pipeline. And there are proposals up and down the east and west coast that we have dubbed the “tar sands invasion”. Even the new NDP government in Alberta, having made its debut in Paris, is now throwing its weight behind reviving the nearly moribund Northern Gateway pipeline to the British Columbia coast, raising questions about Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s promise to permanently ban tankers along B.C.s fragile coast.

Keystone XL has achieved a lasting legacy. The “keep it in the ground” movement is going strong, having sprung like Hydra from the Keystone campaign. But our work will go on until the social license to extract and burn fossil fuels is gone. One can only hope that the unfolding tragedies at opposite ends of the world—last week's news that half the Great Barrier Reef is dead from warming waters and this weeks burning of Fort McMurray—fatally erodes what remains of that social license.