In addition to crusading for clean water here at NRDC during the workweek, in my free time I’m also a volunteer water quality monitor for Arlington County, Virginia, where I live. Once a month I grab a water sample from Four Mile Run, my local stream, and test it for E. coli bacteria. E. coli comes from human and animal waste (yuck!) and is a trustworthy indicator of potential health risks if you should come into contact with the water.

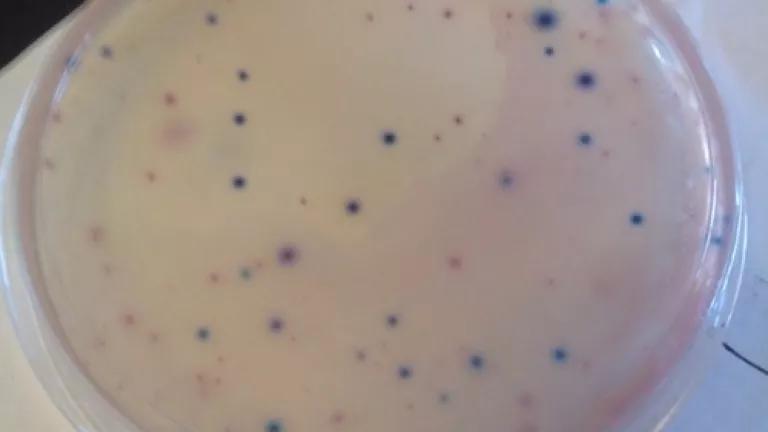

Here’s a picture of my Petri dish from this month’s monitoring:

All of the blue and purple spots you see (but not the pink spots) are E. coli colonies. Pretty colorful, huh? These results violate Virginia’s primary water quality standards, which means that the water I tested was not safe for “primary contact” activities like swimming or wading. Unfortunately, the same day I took this sample, I saw lots of people and pups splashing in the water at a dog park upstream from my monitoring site.

- Dogs and their owners frolicking in Four Mile Run.

Why was the water quality so bad this month? The week before I took this sample, we had a lot of stormy weather in the Washington, DC area. Every time it rains, water washes off of hard surfaces like roads, parking lots, and rooftops instead of soaking into the ground like it would in a natural environment. After running off of these impervious surfaces, stormwater flows through gutters and pipes directly into our local waterways, carrying dirt, fertilizer, trash, oil, grease, metals, and any other substance it comes into contact with along the way.

In Four Mile Run, the biggest problem is waste from humans, dogs, birds, and other wildlife. Dogs contribute over 5,000 pounds of droppings every day to the Four Mile Run watershed, on top of the unquantifiable contributions of wild raccoons and Canada geese. When stormwater runoff carries that waste into the stream, bacteria levels can get high enough to make people sick. (Sewage spills like this recent one are another potential source of bacteria, although they’re fortunately less frequent than rainstorms.)

So if you live near a river or stream where you like to swim or play, here’s a good rule of thumb for knowing if it’s safe to go in: you should avoid contact with the water for at least 24 hours after it rains, and at least 72 hours after heavy rains. And if the water looks or smells funny, it’s best to stay on dry land.

It’s also important to remember that bacteria doesn’t stay put in local streams like Four Mile Run—it continues to flow downstream, along with pollution from other small tributaries, into the Potomac River and ultimately to the Chesapeake Bay. It can end up at beaches where families go on vacation. And this isn’t just a problem in the mid-Atlantic region—it’s happening in communities across the nation, everywhere urban development is transforming natural landscapes into pollution-generating impervious surfaces. In fact, stormwater runoff is the largest known source of beach closings and advisory days nationwide.

Today NRDC released its 23rd annual beach water quality report, Testing the Waters. This report is a useful, comprehensive guide to the bacteria levels and trends at the beaches you and your family like to visit. You can use it to find out whether stormwater pollution has led to beach closings or advisories in your area. Keep your friends and family safe by choosing beaches with better track records of clean water.

In the longer term, you can use Testing the Waters to learn about policies that can help significantly reduce stormwater runoff in your state or town. For example, as part of NRDC’s commitment to cleaning up the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries, we’re fighting for strong stormwater controls that incentivize the use of modern green infrastructure techniques in a number of places throughout the Bay watershed, including Arlington County.

- Buckroe Beach, Virginia, on the Chesapeake Bay. Photo credit: Flickr user Steve Loya

In the meantime, I’ll be “testing the waters” in my own neighborhood, helping Arlingtonians know when Four Mile Run is safe for them and their four-legged friends. I might even take a dip at a downstream beach this summer – just maybe not after a rainstorm.