Quebec Promises Caribou Protection but Urgent Action Needed to Stop Roads into Broadback

This post authored by Liz Barratt-Brown, Senior Advisor to NRDC’s International Program

On April 5, the Quebec government issued broad outlines for protecting woodland caribou in its boreal forest lands, which due to heavy road building, logging, mining and hunting, have led to the precipitous decline of these iconic animals. What will really matter now is what Quebec does to follow up on this new action plan.

Woodland caribou are beautiful but shy creatures that have been synonymous with the boreal forest since time immemorial. They live not in vast herds like their better known cousins, the migratory Tundra caribou, but instead live in isolated groups and feed on ground lichens that grow under a mature forest canopy. Not only are the caribou an iconic boreal species, they are bellwethers for the larger health of the forest ecosystem.

Today, the woodland caribou is at great risk across the boreal. In northern Quebec, scientists studying woodland caribou herds in the James Bay/Eeyou Istchee region, warn that, barring immediate efforts to stem road building and other disturbances in the forest allocated for logging (south of the unallocated northern limit), the decline will continue until the herds are not self-sustaining. Other areas, such as the Saguenay-Lac-St-Jean and Cote Nord regions face similar threats.

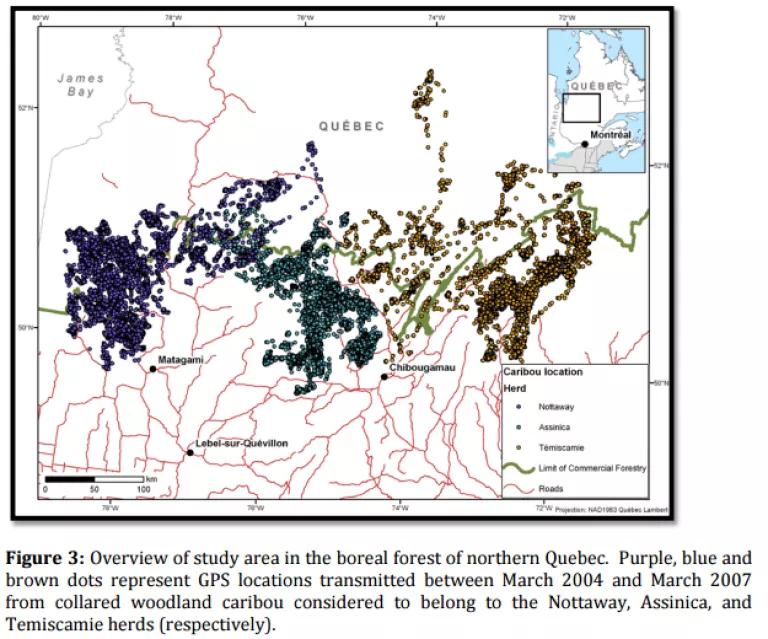

Quebec is no doubt familiar with the scientific data. In the report Status of Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) in the James Bay Region of Northern Quebec presented to the Quebec government and the Grand Council of the Cree in 2012, four prominent caribou scientists found that all the herds assessed—the Assinica, Nottaway, and Temiscamie—are in decline. They recommended that caribou habitat be restored, not further eroded, in order for there to be a fighting chance for these important herds to survive.

Caribou are particularly sensitive to human disturbance and tend to avoid crossing roads even if there is attractive habitat on the other side. This is partly due to the fact that human and animal predators are often associated with roads. Instead, these populations, which require at least 65% of their ranges undisturbed to be self-sustaining, have seen their habitat disturbed and the remaining animals are increasingly being landlocked within a spider's web of roads and clearcuts.

This is the challenge now facing Quebec, especially since these three herd in northern Quebec live bunched around the allocated forest line—the forest land that has been demarcated for present and future logging and where roads continue to be proposed and built (see map below).

Road proposals near the Broadback must be halted as first order of business under this new announcement

Of utmost immediate concern are two roads—H and I—that are making their way through the approval process. The roads would cut into proposals put forward by the Cree First Nation to protect their traditional land and the caribou and are unanimously opposed by the Waswanipi Cree community. A recommendation is expected soon from COMEX, a joint entity made up of Quebec government officials and the Cree government with a final decision made by the Quebec government. There are road proposals at issue throughout Quebec’s allocated forest, including in other intact forest areas, such as around the Montagnes Blanches and referenced in Quebec's announcement. But a decision is expected any day on the two roads near the Broadback River valley.

The government must reject these roads as the very first order of business under this new announcement. As the Waswanipi Chief Marcel Happyjack said at a recent press conference, "Our message is clear: no more development can be allowed in the Broadback River Valley, for the sake of our planet, the survival of the caribou and the protection of our Cree way of life." As noted, caribou are a bellwether species that reflect overall ecosystem health of the boreal forest. The boreal forest holds 30% of the terrestrial carbon on the planet in its soils and trees. The Waswanipi understand this more than any others and Chief Happyjack made clear in his statement that they are stewards in this broader sense—that in this day and age it is unconscionable to further degrade the boreal forest landscape and lose the incredible value of its biodiversity and carbon storage capacity. This is why the Waswanipi see their role as more than just guardians for their own peoples but for the entire planet.

It is in this light that the Waswanipi Crees have asked that their protection proposal for the Broadback River valley be granted by July, 2016. Meanwhile, the larger Cree government is seeking broader protection for the Broadback watershed. As these negotiations play out, the Waswanipi Crees have agreed not to harvest any caribou even though it has, like moose, been a staple of their diet for many years. They understand that there is no time to lose and are asking that the government respect that.

Looking across the boreal, the picture is not a lot rosier.

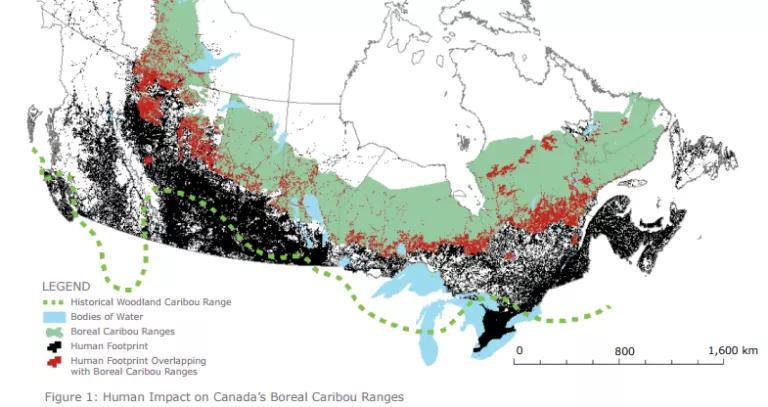

Since 2002, woodland caribou have been listed as threatened under Canada's Species at Risk Act. Environment Canada in its 2011 scientific assessment of woodland caribou found that thirty seven of Canada's fifty one populations of woodland caribou have fallen below sustainable levels.

That is not for any lack of advocacy for caribou protection. For years, Indigenous Peoples and environmental groups have argued that much more needs to be done. Woodland caribou, according to a report by the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS), now occupy half of their historic range across Canada. Habitat fragmentation is the main driving force in their decline, which can only be addressed by protecting large areas of within their historic range.

Back to Quebec—the time is now

Since 2012, when the Federal Government announced its Recovery Strategy for the Woodland Caribou and 2013 when Quebec updated its Provincial Recovery Plan, here in French, the Quebec government has promised a management plan. Four years on, a specific management plan is still pending and details on how Quebec hopes to achieve protection for caribou remain alarmingly sparse.

Additionally, under this plan, called the Quebec Plan, the province has made a commitment to protect large areas—up to 10,000 square kilometers. These areas would serve as "conservation cores" and should be interconnected since caribou home ranges are extensive. In the northwestern portion of Quebec, in the James Bay/Eeyou Istchee region, the 2012 caribou report discussed above found that ranges were 27,900 km2 for the Assinica, 36,400 km2 for the Nottaway, and 47,500 km2 for the Temiscamie. Remember that these herds require a minimum of 65% of their ranges undisturbed. Doing some simple math and putting these numbers together, and subtracting about 6,000 in territorial overlap, the historic range of these three herds is over 100,000 km2. At 65%, the number is nearly 70,000 km2.

Since the caribou scientists' report was issued in 2012, CPAWS reports that only 5,436 km2 has been protected in this area of Quebec and that, according to the Waswanipi Broadback Task Force, that protection is in parts of the Broadback River watershed that have experienced fire and includes parts of the forest north of the allocated forest line. In other words, more needs to be done.

Quebec claims to have a world class forestry regime. Part of a world class forestry regime is ensuring that other forest values are protected and that forestry operations are truly sustainable. In other words, that the forest allocated to logging can regenerate and not expand its footprint as a result of forest degradation due to over-logging. It is therefore alarming that Quebec has floated moving or expanding the northern boundary to accommodate forestry. Under a world class regime, there can be no expansion of the industrial footprint until there is clear proof that caribou herds are self-sustaining.

Quebec has some of the richest and most extensive remaining boreal forest land in the world and all eyes are now turning to Quebec since British Columbia made its announcement on February 1 that it would protect 85% of its Great Bear Rainforest. Now it is Quebec's turn to show on the ground that it does indeed have world class standards. The first test is the woodland caribou.

Questions we'd like to ask

Quebec has put out the broad outlines of a plan but many questions remain. Here are a few of the questions we would like to hear the Quebec government answer:

- Will Quebec deny the two roads currently pending before the COMEX that imperil the Broadback River valley and the woodland caribou herds found in that area?

- Will the Quebec government adopt its Recovery Plan issued in 2013 and announce a management plan for implementing it?

- In its broadest statement, Quebec says it will protect 90% of its intact forest, but where will those intact forests be? How much new protection do they plan to grant from the presently allocated forest or is all protection slated for north of the allocated forest, leaving the intact forests located in the commercial zone at risk of being converted to logged forests? Will Quebec adjust the northern boundary line?

- While Quebec mentions there are proposals pending for the Montagnes Blanches and Rene Levasseur Island regions, they don’t mention that the Waswanipi and Cree Nation proposals for the Broadback watershed region that are also pending. Why aren’t these proposals specifically referenced?

- Will Quebec demonstrate strong support for Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) as a sustainable forestry certification system as well as FSC’s requirements that emphasize caribou protection?

- Will Quebec address mining, poaching and wildlife depredation that also effect caribou in these forests?

The new Quebec policy will require a great deal of immediate work to help alleviate the tremendous pressure the woodland caribou are under from human action. Caribou science tells us this is our last chance to save Quebec herds that are on the cusp of extinction.