Today the Department of Energy announced a new set of efficiency standards for refrigerators, the seventh set of state and federal standards for refrigerators over the past 35 years. DOE estimates that the 30-year savings from this new requirement will be almost 5 Quads, equivalent to the entire energy consumption of all the homes in the nation for two months.

This should sound surprising – how can further energy savings be possible after the gains we have already made in refrigerator energy efficiency? The first efficiency standards for refrigerators were established in 1976. They eliminated the least efficient half of the market, and by 1987, after the second tier of state standards, the first round of federal standards, and a round of utility-sponsored incentives, the least efficient refrigerator used less electricity than the best model of 1975. But further savings were found after this, and realized by the complementary action of Energy Star recognition, financial incentives, and new standards. But despite the great leaps and bounds in refrigerator efficiency over the past 4 decades, continued innovation and improvement has led to further potential cost-effective savings – and refrigerators remain one of the top ten efficiency resources among appliance and equipment.

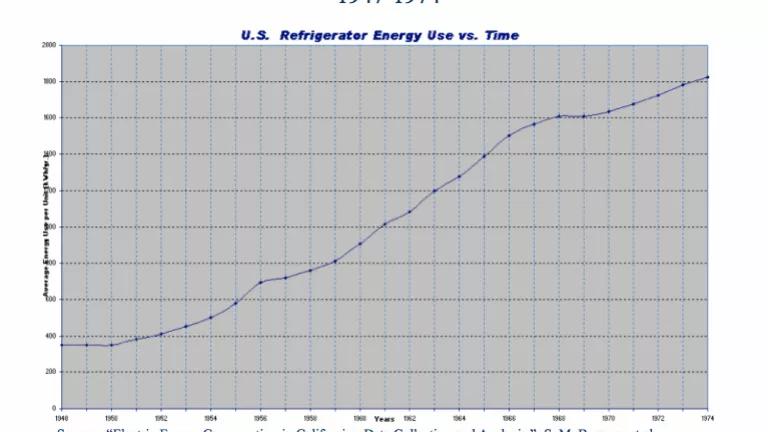

Efficiency standards have driven this innovation: this fact is apparent from Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 shows how energy efficiency was actually declining every year until the mid-1970s when standards were introduced by California. Until the first standards, there was no market for efficiency, and the failure-ridden market rewarded the worst kind of “innovation”: changes in refrigerator design that actually made energy consumption grow from year to year for 25 years, saving consumers a few dozen dollars up front while costing them a few hundred over the life of product. But standards, and accompanying incentives, ranging from rebates offered by utilities, marketing assistance from the EnergyStar program, federal tax credits for efficiency, and the Golden Carrot program (sponsored by utilities and states), solved this problem by aligning the interests of the consumer and the environment with the profit motive of the manufacturers.

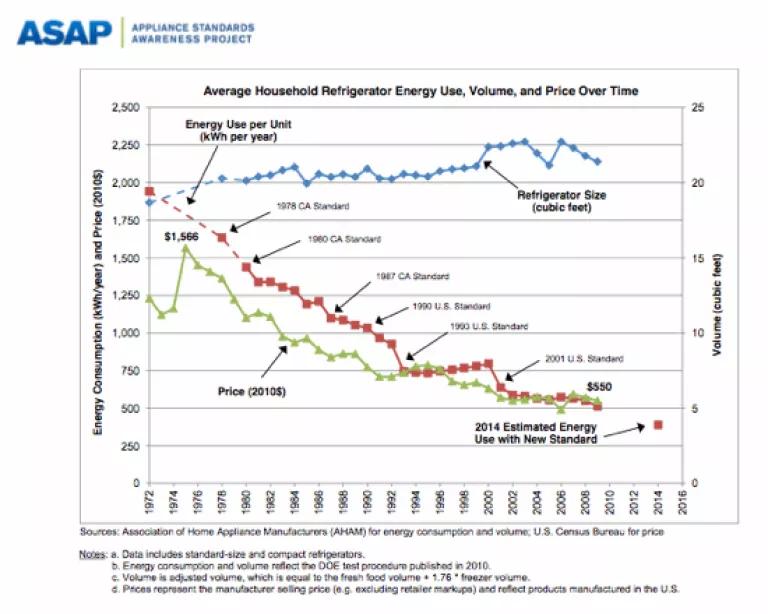

As a result of this suite of policies, refrigerators got better year after year after year. Figure 2 illustrates the results. Not only that, but in the process manufacturers improved the features and quality of the product. My own refrigerator is quieter than its predecessor, and keeps food fresher for longer; the predecessor (vintage 1981) was similarly better than what came before.

This figure also demonstrates the scope of the improvement: it shows how the size of the product kept increasing while the price, including both feature and size growth but also shows price decreases in the face of better features and more efficiency. For a fuller discussion of the history of refrigerator efficiency and the role of smart energy policy, see Invisible Energy.

Figure 2 demonstrates the power of continual improvement. American manufacturers can make better products every year when there is a market reason to do so. Standards and financial or marketing incentives create those market reasons where they are otherwise lacking. This suite of policies not only benefits consumers and the environment, but helps manufacturers to maintain or create American jobs and to increase their profits; that is why the refrigerator manufacturers negotiated and then urged DOE to adopt the new standards (which included joint lobbying for new efficiency tax incentives and EnergyStar upgrades).

Efficiency has often been called the low hanging fruit, since it is cheaper and faster, as well as greener, than any other resource. But the tree that grows this fruit is special as well: when you pick the fruit, as we have almost a dozen times with refrigerators, it grows back.

Efficiency standards not only increase product quality, they also increase consumer choice. In 1972, before there were refrigerator efficiency standards, consumers had little choice with regard to efficiency. Even though it was possible to make products almost 40% lower in energy use at a price increase that paid itself back more than 6 times over the life of the product, no manufacturer offered one. Now the consumer can buy products that minimally meet the energy standards, or the 20% better Energy Star labeled products, or even those that beat EnergyStar by another 10%. Not to mention the fact that new refrigerators offer more configurations and more frequently offer options such as through-the-door ice dispensers.

These standards provide evidence that environmental regulation produces jobs and makes the economy grow. Manufacturers as well as environmentalists recognized long ago that innovations that were profitable to the producer and saved money for the consumer, as well as reducing pollution, were thwarted by market failures. A suite of policy interventions, including tax credits, utility-sponsored incentives, Energy Star labeling, and standards could overcome these failures and produce a win/win solution.

Standards have been an essential part of making markets work for energy efficiency since they were initiated in 1976. While a naïve reading of economic theory suggests that unregulated market forces produce the best outcome, more careful look at economic data and theory shows how standards are an essential part of a policy package that overcomes failures of the market. Both manufacturers and consumers now recognize that they can produce and buy more innovative products that deliver better consumer value and greater manufacturer profit with standards, market recognition programs such as Energy Star, and performance-based incentives. All three policies are part of the package that environmental organizations, consumer organizations, and manufacturers joined together to support.

Bottom line: efficiency standards boost innovation and competition, and help make industry more profitable and more job-producing. They are part of a suite of policies that produce continual improvement, making the environment cleaner every year and making the economy grow and produce jobs.