(updated December 11th 2009, February 9th, 2010)

A recent administration analysis requested by five industrial state Senators concludes that climate legislation passed by the House and under consideration in the Senate will effectively cap and reduce U.S. global warming pollution without harming the competitive position of American manufacturers and without shifting their emissions or jobs abroad.

The House and Senate bills establish a carbon pollution cap covering power plants, transportation, and large industrial facilities – three sectors of the economy that account for about 85 percent of U.S. emissions. The industrial facilities covered under the cap include so-called “energy-intensive, trade-exposed” industries (“EITEs”). Examples include producers of steel, aluminum, and cement. (Oil refiners are not considered EITEs but have their own separate allocation.)

In September Senators Bayh, Specter, Stabenow, McCaskill, and Brown asked the administration to assess whether provisions in the House-passed American Clean Energy and Security Act would effectively prevent the outsourcing of production, emissions, and jobs in energy-intensive industries that face significant foreign competition. (Their letter is in Appendix C of the report.)

Many of these industries and their labor unions argue that foreign competition prevents them from passing on most of their carbon compliance costs. If they try, they will lose business to foreign suppliers, they say. If they eat the extra costs, they will lose profitability with the same end result.

The House and Senate bills address those issues with three mechanisms:

- First, for a transitional period, the bills allocate free allowances to EITE industries to cover their direct carbon emissions. Eligible firms receive allowances based on their industry’s average emission rate in recent years and the individual firm’s current production rate (output). By using the output metric for issuing free allowances, each industrial sector is encouraged to improve the carbon efficiency of their production. These allocations taper off gradually through 2035.

- Second, the bills reduce energy-intensive manufacturers' electricity costs by giving free allowances to local electricity and natural gas distributors with instructions to pass the value of those allowances onto their customers, including industry. These allocations also taper off gradually over a similar period.

- Third, the House bill creates a “border adjustment” – a requirement to buy special emissions allowances when importing commodities such as steel or cement. The border measure takes effect in 2020 unless appropriate climate agreements are made with other nations where the competing industries are located. (The Senate proposal contains placeholder border adjustment language to be filled in later.)

In combination, these measures are intended to counter incentives for American industrial consumers such as automobile manufacturers or construction firms to buy steel, cement, and other commodities from countries that do not have comparable carbon limitations, and thus to prevent any potential competitive disadvantage that might otherwise be created by curbing carbon. In addition, the bills include broader incentives for industries to modernize and become more energy-efficient. These provisions can help reduce firms’ competitive exposure by reducing their energy-intensity.

In response to the Senators’ request, the White House led an interagency process to assess data on EITEs’ emissions and allocation needs. The interagency report was issued last week.

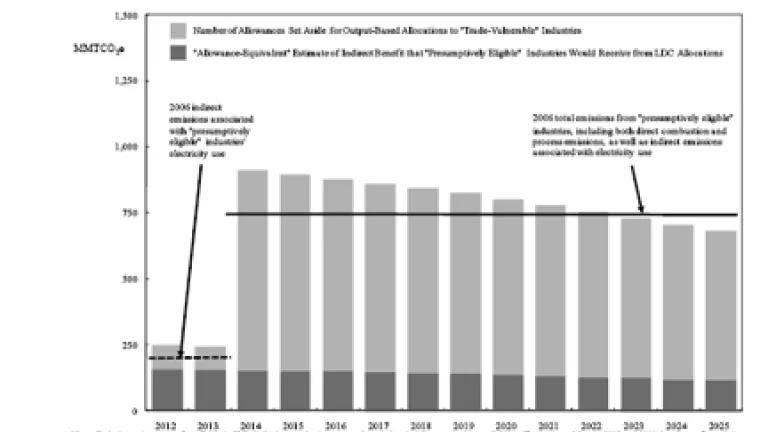

- The interagency report shows that the allocation formula in the House-passed bill gives EITEs sufficient free allowances to cover all of their emissions through 2025. After that date this transitional assistance slowly tapers off (figure 1).

Figure 1 (go to page 36 of the interagency report to see the legends more clearly)

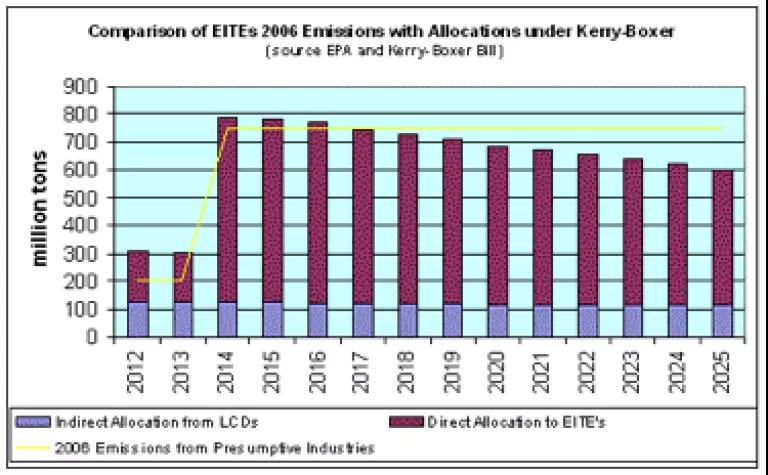

The interagency report did not address the bill passed in November by the Senate Environment Committee, the Kerry-Boxer bill, which allocates slightly fewer allowances to all categories because of Congressional Budget Office scoring rules. So NRDC used the same methodology as the interagency report to assess that bill’s coverage.

- We calculate that allocation formula in the Kerry-Boxer bill would serve the EITEs only slightly less well, giving them sufficient free allocations to cover 96 percent of their emissions through 2025 (figure 2).

Figure 2 (source: NRDC)

The interagency report shows that under the House-passed bill EITEs’ production costs increases would be negligible (0.1 percent on average) when both the output-based allocation for direct emissions and the allocation to electricity distributors are considered. This will keep net imports from rising by more than 1 percent and hold carbon emissions “leakage” to less than 5 percent of total emission reductions.

The report also found that if included under the cap, EITEs will experience 50 percent greater improvement in their energy intensity by 2020, compared to the no-regulation case, helping to reduce their emissions while making them more globally competitive. The report did not evaluate, however, how these industrial efficiency improvements will lessen firms’ need for free allowances.

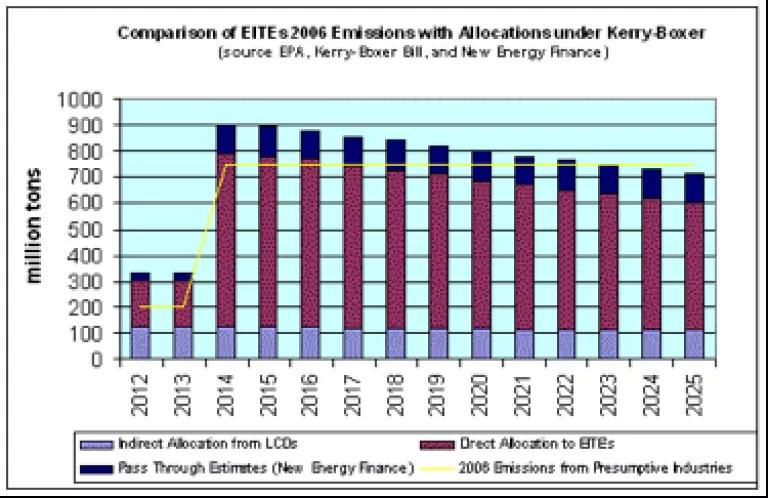

The administration report did not examine the capability of EITEs to pass on a portion of their compliance costs. It simply assumed zero pass-through. This makes the assessment of their allowance needs overly conservative, because many of these industries can pass on some of those compliance costs. Financial analysis on the Kerry-Boxer bill by analysts at New Energy Finance suggests that the percentage of costs that EITEs can pass on ranges from near-zero for aluminum to about 25 percent for cement. New Energy Finance estimates that, as a group average, EITEs can pass on approximately 15 percent of their compliance costs. When average pass-through capacity is taken into account, NRDC estimates that the amount allocated to EITEs as a whole may be more than needed to meet their compliance costs during the first decade (figure 3).

Figure 3 (source: NRDC, from New Energy Finance analysis)

Allocating more allowances than necessary to compensate the eligible industries is a potential problem because it uses up allowances needed for other worthy purposes, including other programs to improve industrial energy efficiency. There also could be WTO issues if EITEs receive more than their actual costs.

So overall it looks like the House and Senate bills do a good job both of capping and reducing the energy-intensive, trade-exposed industries’ emissions and of preventing emissions and job shifts due to foreign competition. They may even allocate more allowances to this program than needed.

Perhaps this is why many firms in these industries have concluded they are better off inside the carbon tent than outside. Why not? They get a gradual emission reductions pathway, transitional allowances to fully cover their costs for more than a decade, and a clear public policy on global warming to guide their investment decisions.

Maybe those companies still agitating to be left outside the tent should think it over again.