What’s Resilience? It’s Not More Fuel or Higher Prices, PJM

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) early this year rejected the Department of Energy proposal that would have further subsidized coal and nuclear power plants, and instead opened a new proceeding to investigate the concept of resilience on the interstate transmission system that it regulates (known as the bulk power system). We along with other environmental and consumer advocacy groups filed multiple sets of comments today to respond to FERC and PJM, the regional grid operator serving 65 million electricity customers in the Mid-Atlantic and Midwest.

Resilience is the Wild West of reliability, and to bring order to this space, FERC and the regional grid operators it oversees—including PJM—must first figure out how to define, measure, and assess resilience and then procure and compensate for resilience-related services—if needed. (The local, low-voltage distribution systems are also key to ensuring resilience to the electricity customer, but FERC does not regulate them. Thus, we only discuss resilience on the interstate bulk power system here.)

While FERC and PJM have floated definitions for resilience (loosely, the ability to anticipate, withstand, reduce the impact of, and quickly recover from disruptive events), they have not explained how resilience differs from grid reliability, provided guidance as to how resilience can be measured or assessed, or under what circumstances should a resilience and/or reliability framework apply.

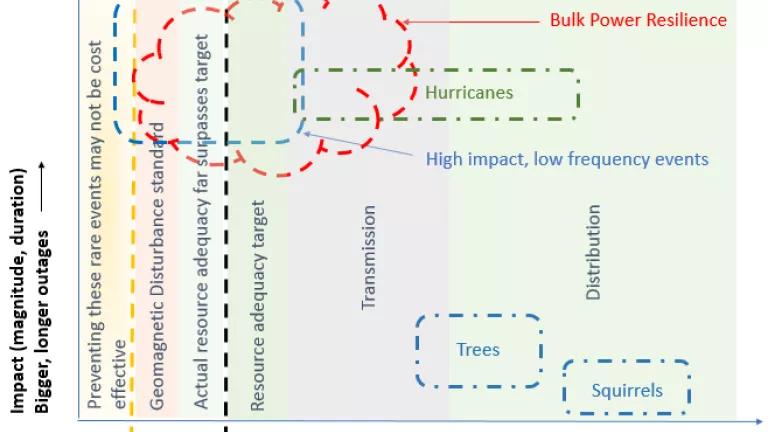

For example, resilience is often discussed in terms of high-impact, low-frequency events—but it's not limited to such events, whereas maintaining reliability means that grid operators need to recover from all events regardless of the impact or frequency. Mapping what falls under reliability and what could fall under resilience for the bulk power system, it appears that the existing reliability framework covers the entire spectrum of events, while resilience is an undefined subset of that (depicted as the nebulous dashed red cloud below). In other words, FERC’s and PJM’s proposed definitions do not clarify what would be covered under a new resilience framework that is not already covered by the existing reliability framework (or an improved version of it). This would create confusion for industry as to what standards—reliability or resilience—would apply, and put customers at risk for paying twice for essentially the same service (once for reliability and again for resilience).

This graph shows that bulk power system reliability already covers generation or resource adequacy; rare, once-every-100-year events like geomagnetic storms resulting from solar activity; as well as the high-voltage transmission infrastructure. Some events, like interference from animals or fallen trees, are frequent and affect the distribution system, while events like hurricanes may happen once every few years but can cause a lot of damage to both the transmission and distribution infrastructure. (Note that this figure is not to scale. The orange region indicating rare events that might not be cost-effective to prevent, versus recover from, may extend farther to the right than depicted.)

More work is needed to develop resilience as a workable concept on the bulk power system, but in the meantime, some proposals put forth in the name of resilience would amount to speculating for gold in that uncharted territory before a proper framework is established. Prime examples are attempts to value “fuel security” or propose market rule changes that would inflate market prices in a way that would encourage more power plants to come or stay online despite the fact that fuel supply or having enough generation available are not at issue for ensuring resilience or reliability.

While ensuring fuel security may sound reasonable at first, no one has been able to demonstrate that compensating power plant owners for always having fuel available would actually ensure resilience or reliability, and if so, whether it’s the most cost-effective means compared to alternatives.

Today, customers pay for reliable electricity service, and folded into that is the requirement that if a resource needs to burn fuel to reliably produce electricity, it needs to make sure it has fuel—as well as ensure that its power plant equipment works. Further, the poles and wires needed to deliver electricity must also be operational. Having fuel on hand is no use if equipment is malfunctioning (which has been the case during extreme winter weather) or if power lines are down (which is usually the main cause of outages, e.g., during hurricanes). In fact, having fuel onsite has been proven useless when coal piles froze during extreme winter storms or became soaked with water during hurricanes.

Further, fuel-free resources like wind power are strong performers during severe winter weather and can help to ensure resilience. Focusing on fuel security ignores these and other cost-effective alternatives that grid operators can employ to maintain reliability and resilience, which include paying customers who can delay or reduce electricity use to do so, or leaning on energy storage and distributed generation sited near customers (which are less vulnerable to broken power lines).

PJM, in its resilience filing at FERC, proposed a number of market rule changes and asked for a 9- to 12- month deadline from FERC to file detailed rules for all of these proposals. PJM, however, has acknowledged that its system is reliable and has not demonstrated why these market proposals have anything to do with ensuring resilience or why such a short deadline is needed. Even though we support the basic concepts underlying the proposals for distributed energy resources and valuing flexibility, PJM also proposes market changes that would be detrimental to clean energy and consumers and undermine basic economic principles. In our comments, we’re asking FERC to reject PJM’s request to FERC, as it amounts to pressuring PJM stakeholders to adopt market rule changes without being able to fully vet them. (PJM requested that FERC require such filings and impose a deadline for all regional grid operators and not just for PJM. In response, all other FERC-regulated regional grid operators jointly filed at FERC to oppose PJM’s request.)

There are many approaches to addressing resilience, but adequate process and coordination are required to do it right. Rather than view resilience as a means to enrich special interests, FERC, states, and regional authorities need to coordinate to comprehensively investigate resilience, figure out how to measure various aspects of it, prioritize issues and potential solutions, and to do so on a reasonable timeline. As we’ve seen in Puerto Rico and other storm-ravaged areas, we need to develop solutions to help electricity customers, not burden them with what amounts to needless bailouts to fossil and nuclear interests.

Our comments on PJM-related resilience topics are available here, here, and here.