I’ve spent the last three days (along with my NRDC colleagues and other clean water experts) listening to more than two dozen scientists debate questions such as: are tributary streams, wetlands and open waters physically, chemically and biologically connected to downstream waters (spoiler alert: the answer is a resounding yes!); what kind of connections do so-called “isolated” waters, such as vernal pools and prairie potholes, have; and how do temporal and spatial changes affect connectivity?

These are not esoteric questions – the answers to these questions will affect the drinking water supplies for more than 117 million Americans, as well as the health of the rivers, streams and lakes in our backyards and where we fish, swim and canoe.

These questions are at the heart of a debate about what types of waterbodies are covered by the Clean Water Act; as my colleague Melissa Waage described, we arrived at this point after muddled court rulings in 2001 and 2006 created uncertainty over whether certain kinds of waters—such as small, headwater streams that feed larger water bodies—are protected under the Clean Water Act.

EPA summarized the peer-reviewed literature about how these tributary streams, wetlands and other “isolated” waters are connected; and this is where the scientists come in. EPA convened a Science Advisory Board of the nation's top clean water scientists is to review their work and to accept comments from members of the public, including my colleague Jon Devine.

As my spoiler alert indicated, the scientists overwhelmingly support two of the major conclusions of the report:

1) the scientific literature demonstrates that streams, individually or cumulatively, exert a strong influence on the character and functioning of downstream waters, and

2) wetlands and open-waters in landscape settings that have bidirectional hydrologic exchanges with streams or rivers are physically, chemically, and biologically connected.

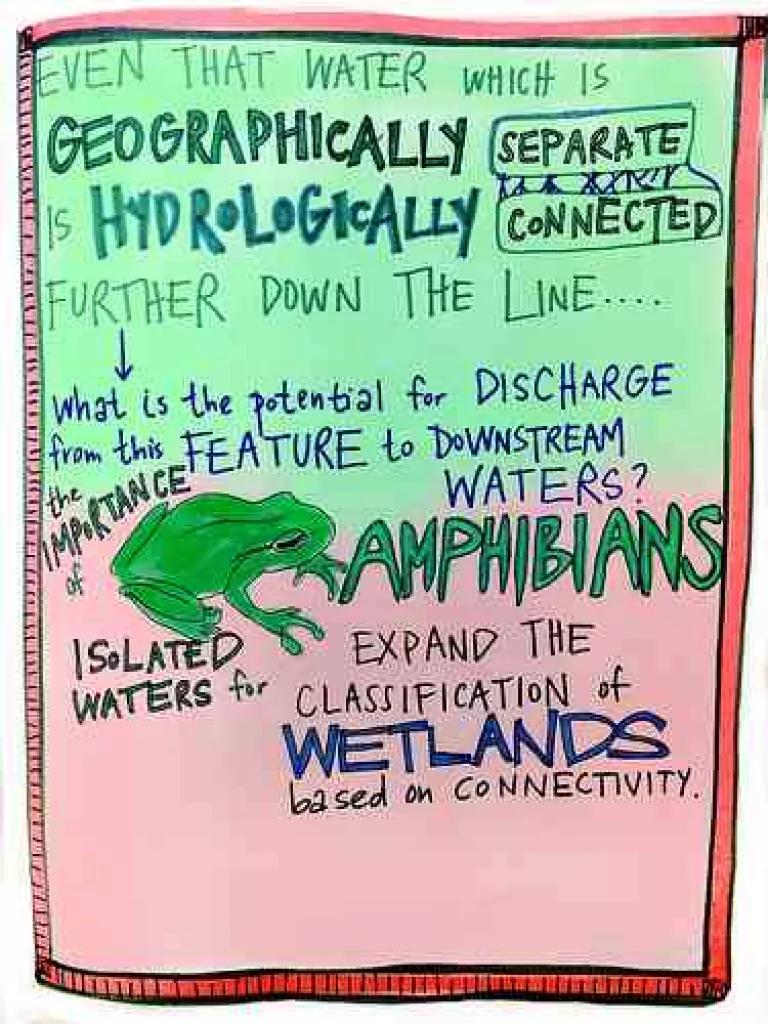

But the far thornier question is whether or not “isolated,” or what EPA’s report characterizes as “unidirectional” wetlands, such as Carolina bays, vernal pools, playa lakes and prairie potholes, are physically, chemically and biologically connected to downstream waters. A quick definitional note: these waters can periodically dry out and are not permanently, physically connected to waters such as lakes, rivers, or streams. EPA’s draft report presented a lot of scientific evidence about how these waterbodies actually impact downstream conditions but then inexplicably concluded that the “literature we reviewed does not provide sufficient information to evaluate or generalize about the degree of connectivity.”

And this is where science really had its day. When the scientists started discussing this point, they almost immediately rejected the idea that there’s a question of connectivity, but rather the question is “how much” connectivity between these waters. And, just as important – over what time period and scale does that connectivity exist? As one of the scientists, Dr. Emily Bernhardt of Duke University observed, “Over a sufficient time scale, almost everything is connected.”

For example, many of these wetlands are breeding habitat for amphibians. The frosted flatwoods salamander can only breed in isolated wetlands, along with at least 27 other species of amphibians in the Florida panhandle.

Isolated wetlands provide more than habitat – they also capture and store floodwaters, preventing downstream flooding and minimizing pollution flows.

So, ultimately, what the scientists have to grapple with is where on this “gradient of connectivity” do different types of waterbodies lie? For example, Carolina bays are depressional wetlands that occur on the Atlantic coast. EPA’s draft report showed a range of physical, chemical and biological connections between Carolina bays and downstream waters, including how they provide habitat for scores of species, how they are physically connected to other waters via groundwater, and how they capture and store nitrogen, a source of pollution for downstream waters.

(Photo courtesy of Soil Science @ NC State)

When the scientists finish their report over the coming months, EPA will use their findings to guide a rulemaking that will clarify the scope of legal protections.

We’ll continue to closely monitor this process to make sure that EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers protect ALL of the waterbodies that science shows have physical, chemical and biological connections, as required by the Clean Water Act.

But your favorite stream, wetland or lake needs your support as well -- weigh in with President Obama and ask him to stand up to polluters and fix the Clean Water Act loophole here.