Though it may be hard to believe given that parts of the Northeast had snow showers in recent weeks and Denver is digging out from a major snowstorm, summer is right around the corner. It won’t be long before we’re looking for ways to beat the heat, whether it’s going for a dip in a neighborhood pool, sitting under a shady tree, or (my favorite) hitting up the local ice cream stand. For those of us in the energy efficiency world, summer is also synonymous with air conditioning and higher electricity use.

The US Department of Energy (DOE) took the first step today to making portable air conditioners more efficient, by releasing a determination that this equipment qualifies as a covered product under the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA). This means that, for the first time ever, DOE starts the process of setting standards for portable air conditioners, so that customers who use this product to cool their homes can rest assured that they’re not wasting energy while staying comfortable.

DOE already sets energy efficiency standards for central air conditioners and room air conditioners, both of which are due for an update in 2017. But until now, portable air conditioners—the standalone, moveable units that are not permanently installed in walls and windows—have not had to meet any efficiency standards. Nearly a million portable air conditioners were purchased in 2012, and that number is expected to increase by almost 80% by 2018. This means that the large (and growing) number of Americans who use portable air conditioners to keep cool are likely doing so at a higher-than-necessary cost.

DOE’s announcement marked an important step in establishing an energy efficiency standard for portable air conditioners. Read on to demystify the standards-setting process! I’ll be back next week with tips to save energy on your cooling bill this summer.

Why are some products covered by efficiency standards and others aren’t?

Since the first appliance and equipment standards were authorized by President Ronald Reagan in 1987, the legislation has been revised and DOE now establishes minimum efficiency standards for more than 60 products accounting for 90 percent of home energy use. Since the initial guiding authority specifying 19 products, DOE has added new consumer products (including portable air conditioners) based on 2 main criteria: 1) is a standard necessary and 2) does the product consume a minimum threshold of energy to warrant a minimum efficiency standard. If the answers to these two questions are both affirmative, then the product is determined to be covered and the standards process is initiated.

Demystifying the Standards-Setting Process

What’s next for portable air conditioners?

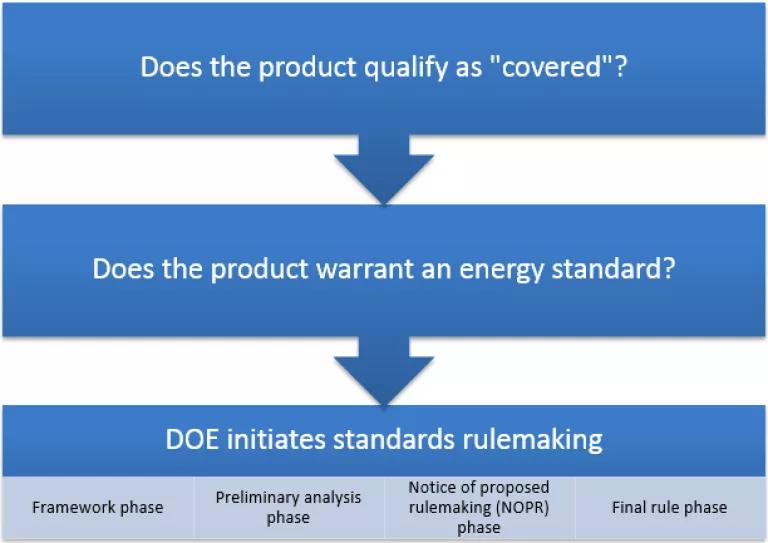

Determining that a product is covered under the provisions of EPCA is necessary before a standard can be established. The flow chart above provides a helpful way to think about the standards process, but note that DOE often starts their analysis of a product before a determination of coverage is made. DOE must also determine whether the portable air conditioners warrant a minimum energy efficiency standard, by analyzing the following:

- average household energy use of the product,

- the total energy use of the product across the country,

- whether a substantial improvement in energy efficiency is technologically feasible, and

- whether a labeling rule (rather than a full-blown energy standard) would be sufficient to induce the maximum energy efficiency.

DOE’s notice of proposed rulemaking, the next major step in the rulemaking process, will include DOE’s proposals for minimum efficiency standards. Rulemakings take about three years to complete and generally consist of four phases: framework, preliminary analysis, notice of proposed rulemaking (NOPR) and final rule. The framework phase is the first step in this process, and sets up the basic outline for the rulemaking. DOE also seeks feedback on specific questions in this phase, which is then fed into the preliminary analysis phase. In this phase, DOE gathers data and information about the technical, economic, and market characteristics of the product, and makes initial determinations of possible efficiency improvements. DOE then takes public feedback on their analyses and issues a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, which includes a proposed efficiency level that is both technologically feasible and economically justified. Taking into account additional public comment on the proposal, DOE issues a final rule, which generally goes into effect within 3-5 years.

Depending on the level of information DOE already has available, the standard-setting process could potentially start at the preliminary analysis or NOPR phase. Standards can be negotiated in conjunction with the Appliance Standards and Rulemaking Federal Advisory Committee (ASRAC) or they can be established through a traditional, non-negotiated process. If ASRAC decides that a standard should be negotiated, they form a working group comprised of parties that are representative of various points of view—manufacturers, efficiency advocates, States, and so on. Once the working group reaches a consensus, DOE can issue either a NOPR or a Direct Final Rule. Standards can also be set through informal negotiations, under DOE’s Direct Final Rule authority.

The pieces of the standards-setting process are coming together for portable air conditioners, and the way forward is clear. The appliance and equipment standards program has a rigorous, proven process that has led to extremely high levels of energy savings in its almost 30 years of existence. We’ll keep pushing to make sure that consumers benefit from high-quality products that minimize energy waste.