Building Resilience, BRIC by BRIC

FEMA has announced the first selections for its new Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) grants. Did the first year of the program live up to its promises?

The four categories of BRIC funding are the national competition, management costs, the state/territory allocation, and the tribal set-aside.

This summer, it seems like every day brings yet another deadly heat wave, flood, fire, or hurricane. Living with climate change is no longer a problem for the future—it’s here and it’s now. Faced with an urgent need to reduce the risk from climate-driven hazards, local and state decision-makers are looking to a new program at the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) for funding to support critical resilience projects and protect vulnerable communities.

That program is called Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities, or BRIC for short. On July 1, FEMA announced the first round of selections for the program, totaling $500 million. The selected projects range from small town coastal hazard mitigation plans to multibillion-dollar wildfire resilience programs. On August 9, the agency announced the application period for the program’s second year, which will double available funding to $1 billion.

FEMA leadership has touted BRIC as a key part of the agency’s shift to focus on equity. The program’s website states that it is intended to “categorically shift the federal focus away from reactive disaster spending and toward research-supported, proactive investment in community resilience.” But the project selections suggest that BRIC—like many other programs before it—is primarily protecting areas with highly valued property, rather than people in disadvantaged communities. To meet its self-described mandate, FEMA must continue to adapt its process so that it delivers support to the communities that need it most.

Let’s take a closer look at BRIC’s first year.

A handful of projects account for the majority of BRIC funding…

There are a few different categories of BRIC funding: the state/territory allocation, the tribal set-aside, management costs, and the national competition. The chart below shows how funding was distributed across these categories.

In FY2020, FEMA allocated up to $600,000 for each state and territory to use for capability- and capacity-building activities (like adopting new building codes, project scoping, or mitigation planning) as well as smaller hazard-mitigation projects. The agency also set aside $20 million specifically for federally recognized tribes, and allowed applicants to apply for additional funding to cover grant management costs.

After the state/territory allocations and tribal set-asides were accounted for, the remaining $377 million went to a “national competition,” in which FEMA selected individual projects for funding. The technical term for a BRIC project is a “subapplication,” which reflects the requirement that states and territories compile and submit packages of projects on behalf of local agencies or other “subapplicants.”

As shown in the chart above, the 22 selected projects in this competitive category make up 75% of BRIC funding. (As of mid-August 2021, the projects still need to meet some additional requirements before actually receiving the funding.)

…And most of these projects are concentrated in wealthy, coastal states.

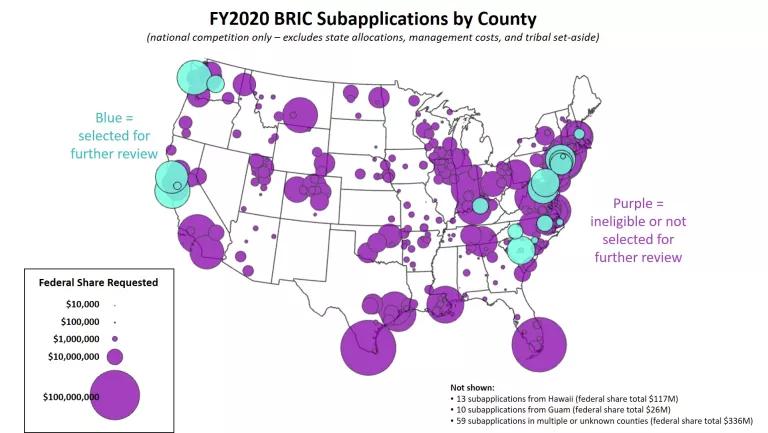

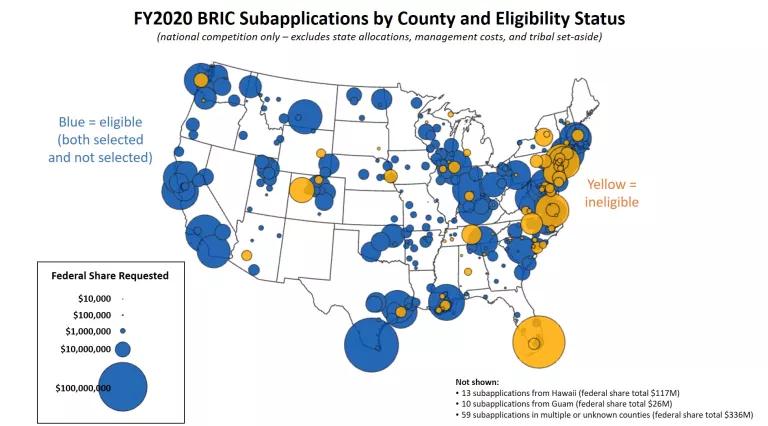

FEMA posted a table with the status of each subapplication on its website, but the specific locations of projects aren’t included, so I took on the task of assigning each entry a county/location. Ultimately, I was able to assign counties to about 90% of the subapplications in the national competition and 65% of the projects in the other funding categories. (Some subapplications are for statewide activities or for projects spanning multiple counties, and others’ locations couldn’t be determined based on the project name.) This allows us to look at the locations of the projects that were selected—and not selected.

The map below shows the subapplications in the national competition. The light blue circles represent the 22 projects that FEMA selected, and the purple circles are those that FEMA deemed ineligible or that were eligible but not ranked highly enough to be selected. The circles are sized proportionally to the amount of federal BRIC funding requested, not the overall cost of the project.

The 22 projects selected from the national competition are located in 10 states.

You’ll notice that there are very few selected projects (in blue) compared to those not selected (in purple). The selected projects tend to be more expensive, with higher non-federal cost shares. They also tend be located in counties that have high expected annual losses according to FEMA’s National Risk Index but, with a few exceptions, only moderate-to-low social vulnerability. In other words, the selected projects tend to protect highly valued assets, rather than those in disadvantaged communities. This is likely due to a combination of factors (not unique to BRIC) such as the level of local capacity required to complete the application process, benefit-cost analysis requirements, cost share requirements, and scoring criteria. But the result is a program that appears to continue the long-standing trend of prioritizing property over people.

State building codes have a big impact on project scores.

Strong building codes are a highly effective way to protect people and property, and they played an important role in the BRIC selection process. All of the selected projects are in places with statewide building codes (or citywide, in the case of Washington, D.C.) that follow the International Building Code from 2015 or later. One participant in FEMA’s August 11 webinar even asked if applying for BRIC was a “lost cause” for communities in states without strong building codes.

Strong, modern building codes are a key way to reduce disaster risk, and it’s great that BRIC funding can support code adoption and implementation. However, the BRIC scoring criteria mean that cities and counties in states without mandatory building codes are at a big disadvantage. Instead of penalizing localities for something that may be outside their control, BRIC could be used as a tool to encourage and assist more states in adopting stronger codes.

Federal criteria for “small, impoverished communities” leave a lot of people behind.

Many low-income communities and communities of color do not have the staff, capacity, or other resources necessary to successfully navigate the complex FEMA grant application process. Only about 9% of the proposed BRIC subapplications were from “small, impoverished” communities. Two were selected under the national competition: one for resilient infrastructure development in Princeville, NC and one for a vertical tsunami evacuation structure in Westport, WA.

However, the criteria for small, impoverished communities—which are determined by Congress—are very narrow, excluding any locality larger than 3,000 people. This leaves many communities in a “donut hole” where they do not receive priority points or a better cost share but still struggle to compete for funding. In 2021, FEMA is updating its name for this category to “economically disadvantaged rural communities.” For any more substantive changes, though, Congress will need to take action. Meanwhile, FEMA could dedicate funding for capacity building aimed at low-income communities, communities of color, and tribal communities.

States also have work to do.

FEMA’s data show that 35 of the 56 eligible states and territories did not apply for $600,000 in funding allowed to them. Even more noteworthy, FEMA Region 2 and Region 6 (which collectively serve seven states, two territories, and 76 tribal nations) did not receive any applications for non-financial direct technical assistance. It seems unlikely that this many states cannot afford the non-federal cost share, and there are certainly communities in Regions 2 and 6 that would benefit from technical assistance.

Also, some states had a high proportion of projects that FEMA determined didn’t meet the basic eligibility criteria. While overall national ineligibility numbers were similar to other FEMA grant programs, a few states had a majority of their BRIC projects rejected for eligibility reasons, such as not submitting a complete application, or not having a FEMA-approved hazard mitigation plan in place.

In some states, a majority of subapplications were ineligible.

Because local governments can’t apply directly for BRIC, states are ultimately responsible for ensuring interested communities are aware of funding and technical assistance opportunities, supporting them in applying, and making sure that projects are eligible.

Recommendations

In its FY2021 Notice of Funding Opportunity for BRIC, FEMA takes a number of positive steps. BRIC is a pilot program for the Biden administration’s Justice40 initiative, and the new scoring criteria (especially the qualitative criteria) place a higher priority on serving disadvantaged communities compared to last year. The direct technical assistance application process has also been streamlined and FEMA is doubling the number of potential recipients. And a larger pool of available funding—doubled to $1 billion overall—means that more projects can be selected.

Still, FEMA should take additional steps to continue to improve the BRIC program. For example, FEMA could:

- Continue to evaluate its scoring criteria and determine ways to better prioritize projects from lower-income communities and communities of color.

- Allow high-priority capability and capacity-building activities to be funded under the national competition, and incentivize these activities via scoring and/or cost share.

- Create a dedicated set-aside for capacity building, particularly for low-income communities, communities of color, and tribal communities.

- De-emphasize pre-existing building codes as scoring criteria, instead (or also) prioritizing projects that include code adoption.

- Create a dedicated set-aside for nature based solutions, making sure projects that don’t rely on engineered structural measures are able to compete for funding within a pool of similar projects.

- Make building code adoption an eligible activity for the national competition as well as the state/territory allocation.

With increased attention from Congress and the White House, BRIC has a lot of potential to help ease the nation’s growing resilience gap. But work still needs to be done to make sure it lives up to that potential, and NRDC will be advocating for those changes.