At a time when over 50 million people are food insecure and we face an obesity crisis, it’s a shame that 40% of food is never eaten. A closer look shows us that Americans are tossing 52% of the nation’s nutritious fruits and vegetables[i] – wasting produce, more than any other type of food product, including seafood, meat, grains and dairy, at nearly every level across the supply chain.

Some of this massive produce loss is happening well before it reaches retailers, as perfectly edible produce is literally being left on the field or sent to the landfill. And many of these good fruits and vegetables are never even harvested. A new report commissioned by NRDC investigates losses at the farm level.

Some people gamble, some play the stock market, and some grow food. Farming is a risky business that faces the impacts of adverse weather, including crop damage and loss, as a routine part of the business. However, it does not take an extreme weather event, or a weather event at all, for crops to go to waste in the fields. In fact, thousands of acres of perfectly edible produce go to waste every year because of market fluctuations, cosmetic imperfections, and other reasons.

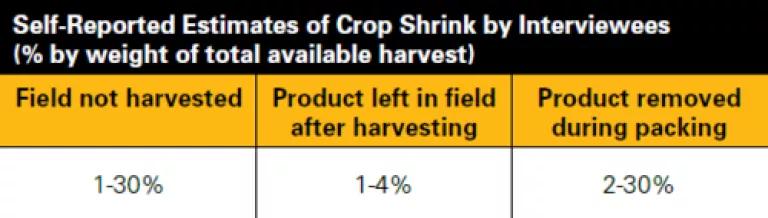

This new crop loss report, written by Milepost Consulting, surveyed a small sample of 16 farmers and packer-shippers (those who distribute the produce) in the Central Coast and Central Valley of California. Results are by no means conclusive due to the limited data set, but they do offer an anecdotal snapshot of the extent of losses that occur. They found that “shrink,” another word for lost product, could be as low as 1 percent for the crops which were studied and, depending on weather and market conditions of a particular year, as high as 30 percent. Losses for plums and nectarines were on the high side; head lettuce and broccoli losses (at least where the farmer was selling florets separately) were relatively low.

This can translate to a lot of food. If just 5 percent of the U.S. broccoli production is not harvested, over 90 million pounds of broccoli go uneaten. That would be enough to feed every child that participates in the National School Lunch Program over 11 4-ounce servings of broccoli.[ii]

It also translates to a lot of resources used for naught. For example, if just 5 percent of broccoli grown in Monterey County, California (producer of 40 percent of U.S. broccoli) is not harvested, that represents the wasted use of 1.6 billion gallons of water and 450,000 pounds of nitrogen fertilizer (a contributor to global warming and water pollution). [iii] And let’s not forget about the energy, pesticides, land, and other resources that went into growing that food. All told, it would amount to about a $12 million bill for broccoli farmers[iv] -- a chunk of change and resources that warrant further investigation into how we might recover and improve upon some of these unnecessary staggering produce losses.

What is causing so much produce to be lost on farms?

Before you scoff at this, know that we are all to blame. In our search for the perfectly round, perfectly colored, perfectly sized peach, we as consumers ultimately drive much of this waste. As explained by farmer and author David Masumoto, “If we picked our friends the way we selectively picked and culled our produce, we'd be very lonely.”

Our finicky preference for perfect-looking produce not only forces some fruit and vegetables to be voted off the marketplace, it drives down the price of even slightly misshapen, smaller, or scarred fruit. A peach grower once told me that for eight out of ten of the fruit he can’t sell, “you wouldn’t even be able to tell me what’s wrong with it.” Yet they are considered lower “grade,” lower grades mean lower prices, and low prices are another cause of shrink.

It costs money to harvest a field. If prices are too low, the farmer would have to pay more for people to harvest the product and for cooling and transport than he would receive in revenue. So, that farmer is forced to deem that field or orchard a “walk by” and turn it back into the soil when possible. Estimates of how often walk-by’s happen ranged from 1 to 30 percent of the time. This mostly happens when the market is flooded with more supply than demand.

There’s more to the story, however. Inherent to the produce industry is a structure of a few large buyers and many suppliers. This leads to a situation where the largest food buyers are able to dictate the terms of a sale, and the growers are generally forced to accept them. These terms can include formal “penalties to deliver” if the grower comes up short in quantity at the agreed-upon level of quality. Even if that’s not required contractually, growers are compelled to ensure they meet the orders for fear they will otherwise lose their biggest customers. Therefore, they do exactly what anyone in their right mind with a riskier-than-average business would do—they plant a little extra for insurance. One grower estimated overplanting about 10 percent on a regular basis. Of course, when harvest time comes, he /she tries to find other markets for the surplus, so it may not go to waste. In aggregate, however, this adds to the overall supply in the marketplace, thus driving prices down and potentially leading again to those walk-by’s.

A farmer might also be forced to abandon a field or entire crop because he/she simply can’t find enough workers to harvest it. Labor shortages are an increasing problem for farmers, as was demonstrated this year when in Washington apple growers estimated losing upwards of 25% of their harvest due to lack of skilled labor.

Another big driver is market fluctuation. With highly variable prices—one broccoli grower had seen prices go as low as $6 per case and as high as $32—growers are constantly guessing on how to play the supply-demand game. One good year can cover a series of bad ones. This can lead to an almost gambling mentality where growers “double down” on what they are planting one year to cover the losses they incurred the previous year. That again creates more supply potentially creating the conditions for walk-by’s.

What can we do about this?

This is complicated stuff. Farmers are juggling a myriad of variables from weather to plants to markets and beyond. A little margin of error is certainly expected. At the same time, from a societal perspective, there is perfectly good, nutritious food out there that is not making it to people who could really benefit from it. Though the problem is occurring at the farm, we all have a part in solving it. Here’s how:

Consumers, let’s all be a little more forgiving in the grocery store (and restaurants for that matter). As David Masumoto beautifully described, “Real foods carry with them the memory of real life. No two peaches are, nor should they be, exactly alike. Natural variation is natural. Culls are part of nature. How they're accepted becomes the question for survival.”

Businesses, you too can be more forgiving in acknowledging the challenges of farming and allowing for the occasional short volume. Why not give your customers a try and see if they might be interested in purchasing a bag of scarred peaches? There may even be opportunity for the creative entrepreneur in scooping up some of that extra produce and creating new products or markets for it.

Policy-makers, this could be a real opportunity to get more healthy food to people. First, we need to understand the dimensions of it better. As I implored in the NRDC report about food waste, we need a more comprehensive look into how many fruits and vegetables are actually going to waste and why. We don’t need to wait for that study, however, to encourage more donations. At the beginning of this year, California started giving a 10% tax credit to farmers for their food donations. States like Colorado and Arizona offer similar benefits. A federal legislation covering more states and more products could further help incentivize donations. Policy to address the significant problem of farm labor shortages is also important to the equation.

Gleaners and food rescue organizations, keep it up! You are doing a service to all of us, and often with mere crumbs of a budget. We should all be throwing more moral, financial, and volunteer support your way. And we should all consider this a problem that we can help solve.

[i] According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, http://www.fao.org/docrep/014/mb060e/mb060e00.pdf

[ii] The USDA Economic Research Service reports that the U.S. produced 1.8 billion pounds of broccoli in 2010, and about 38.1 million children participated in the National School Lunch Program, http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/lunch/AboutLunch/NSLPFactSheet.pdf.

[iii] Assumes 24 acre-inches of water and 180 pounds of nitrogen per acre, according to averages for Central Coast production derived from “Broccoli Production in California,” UC Vegetable Information and Research Center: http://anrcatalog.ucdavis.edu/pdf/7211.pdf. Acreage from 2011 Monterey County Crop Report: http://ag.co.monterey.ca.us/assets/resources/assets/252/cropreport_2011.pdf.

[iv] Assumes $5,038/acre as estimated in the UC Cooperative Extension “2012 Sample Costs to Produce Fresh Market Broccoli”, http://coststudies.ucdavis.edu/files/Broccoli_CC2012.pdf