The potential for new water storage in California is in the news because of Proposition 1, the $7.5 billion water bond on California’s November ballot, which includes $2.7 billion for new groundwater and surface storage (and an additional $800M for groundwater remediation projects). For instance, Sunday’s San Jose Mercury News article outlined four major reasons why the era of big dams ended in California: the best sites are already taken, environmental laws prevent the worst projects, easy federal money dried up, and cities and farms found new ways to create water. Likewise, columnist Robert Green in the LA Times asks all the right questions about new storage, from taxpayer subsidies to cost effectiveness, and highlights the fact that building a new dam doesn’t mean it will fill with water.

Today, NRDC is releasing a short fact sheet on water storage in California, which contrasts the economic effectiveness of investments in regional and local water supplies like water recycling and efficiency with the high cost and economic infeasibility of building big new dams. Although NRDC continues to have significant environmental concerns with some proposals to build big new dams, more often than not it is simple economics that explains why big new dams aren’t being built in California.

To begin with, building big new dams is very expensive, and the water from such projects is generally far more expensive than water created by groundwater storage, water use efficiency, recycled water (indirect potable reuse), or stormwater capture. For instance, the federal feasibility study for Temperance Flat estimates that this project would cost nearly $2.5 billion and would yield only 61,000 to 76,000 acre feet of water per year. The feasibility study for raising Shasta Dam estimates that project would cost $1 billion and only generate 139,000 acre feet of water per year. Taken together, these two dam projects would cost approximately $3.5 billion and would yield an average of 209,000 acre feet of water per year. In contrast, the state has estimated that $1.4 billion in water bond funding for integrated regional water management (IRWM) projects like water efficiency, water recycling, and groundwater cleanup over the past decade leveraged $3.7 billion in local funding and has helped save or create nearly 2 million acre feet per year. Big new dams simply can’t compete economically with these regional and local water supply projects.

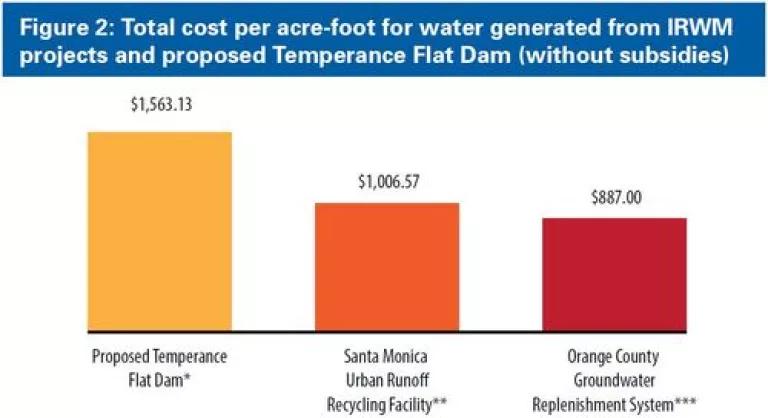

Not surprisingly, these new dam projects produce very expensive water. We estimate that without taxpayer subsidies, the water coming out of Temperance Flat would cost more than $1,500 per acre foot, which is far more than the cost of water generated from water recycling, stormwater capture, groundwater storage, or water conservation projects. Even with massive taxpayer subsidies, the Bureau of Reclamation estimates that water would cost more than $200 per acre foot for agricultural contractors (far more than these districts pay today, especially since the project would eliminate much of the cheap $10 per acre foot water that is provided in wet years). Water generated from big new storage projects costs substantially more than water from water use efficiency, stormwater capture, groundwater cleanup, and water recycling projects. Similarly, research by Stanford University’s Water in the West program, “shows that groundwater recharge is a cheaper alternative to surface storage.”

In addition to the economics, California already has over 1,400 dams and reservoirs, and over the past three decades we have added 6 million acre feet of new water storage facilities, including both surface storage (such as Diamond Valley and Los Vaqueros reservoirs) and groundwater storage (including the Kern Water Bank and Semitropic Water Bank). Because we already have so much existing storage, building new dams does little to create substantial new water supplies. Dr. John Holdren, the White House science advisor, succinctly summed up the problem earlier this year, saying that, “The problem in California is not that we don’t have enough reservoirs, it is that we do not have enough water in them.”

And of course, there are also significant environmental problems with some of the proposed major new storage projects. For instance, as we emphasized in our September 2013 comment letter, raising Shasta Dam would flood sacred sites of the Winnemem Wintu people, flood part of the Wild & Scenic McCloud River (which has some of the best fly fishing in the state), and provide almost no benefits for salmon or other fisheries. Likewise, while our April 2014 comment letter on the draft feasibility study for the proposed Temperance Flat dam focused on the economic infeasibility of this project, we also emphasized that the study’s absurd conclusion that the dam created an ecosystem “benefit” of reduced salmon populations in the San Joaquin River. NRDC strongly opposes these two surface storage projects.

Yet in contrast to these two harmful projects, conservation groups like NRDC did not oppose recent offstream surface storage projects like the Diamond Valley or Los Vaqueros reservoirs, and NRDC has identified potential benefits of additional storage projects south of the Delta like further expansion of Los Vaqueros reservoir, expansion of San Luis Reservoir, and groundwater cleanup and storage projects in the Central Valley and in Southern California. For instance, in the San Fernando Valley water pollution has contaminated the groundwater basin, reducing the amount of water that Los Angeles can withdraw and complicating projects to recharge the basin with stormwater or recycled water. And if the contamination is not addressed, it will continue to spread, further reducing water supplies. Yet by investing in a major groundwater remediation project, LA can sustainably increase the amount of water that is withdrawn from the groundwater basin and enable greater recharge of the basin, helping LA to cut imported water use in half by 2025.

This November, California voters will decide whether to approve Proposition 1. Importantly, the water bond does not earmark funding for Temperance Flat or any other surface storage project, and both surface storage and groundwater storage and cleanup projects would be eligible for funding. In addition, the bond would only provide funding for public benefits like improved water quality or higher salmon returns, and would never fund more than 50% of the total cost of any storage project (so private beneficiaries would have to pay at least 50% of the total cost). If voters approve Proposition 1 this November, we believe it is likely to fund groundwater storage and cleanup projects and some smaller, regional surface storage projects, and we will work over the coming years to ensure that the bond does not provide substantial funding for environmentally harmful and economically infeasible projects like raising Shasta Dam or building Temperance Flat dam.

Even with the water bond, the era of big new dams in California is still over. More than anything, that’s simple economics.