Some things work best when paired together. Music players and headphones. Toothbrushes and toothpaste. Left shoes and right shoes. The same holds true of electric transportation and charging stations.

Numerous studies and reports cite a lack of charging infrastructure as a central barrier to widespread electric vehicle (EV) adoption, and now states are beginning to take serious measures to address that challenge. To alleviate the fear that drivers will run out of juice on the road, known as “range anxiety,” grow the nascent EV charging services market, and combat federal attacks on vehicle emissions standards, states and utilities should pick up the mantle to accelerate transportation electrification.

The New York Power Authority, in an effort to reach the state's fast-approaching ZEV target by 2025 and 40 percent greenhouse gas reduction goal from 1990 levels by 2030, recently launched a $250 million initiative to address key infrastructure and market gaps statewide. The plan includes an initial $40 million investment in three key areas by the end of 2019: 200 Direct Current Fast Charging (DCFC) stations located across the state, new charging hubs at JFK and LaGuardia airports, and EV-friendly “model communities” where utilities manage the charging infrastructure to make electricity affordable and reliable, and the power grid more efficient.

New Jersey is also stepping up. PSE&G, the largest utility in the state, announced its new plan to invest $300 million in "smart" EV infrastructure, along with $2.5 billion in energy efficiency and $100 million in energy storage projects. The utility says it will file the plan with the Board of Public Utilities "later this year." New Jersey's is by far the largest transportation electrification program proposed outside of California. (See the latest news about California’s progress here.)

But how much charging infrastructure do we need to support hundreds of thousands – or millions – of EVs? A new, publicly accessible tool developed by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), EVI-Pro Lite, reveals that many states are far from deploying enough charging stations to reach their ZEV goals.

EVI-Pro Lite is a model that estimates the number of public and workplace charging stations needed to support a given number of light-duty EVs. The tool uses detailed travel data and a range of assumptions regarding vehicle technology, consumer behavior, home charging availability, and other factors, to estimate how many stations would be needed to support widespread EV adoption in particular cities and states.

Many Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic states have adopted California’s Zero Emission Vehicle (ZEV) program, which requires automakers to sell an increasing number of EVs in those states out to 2025, promising billions in vehicle operations, electrical grid, and climate benefits to Northeasterners. Nine states – with New Jersey being the latest – have all signed a ZEV Memorandum of Understanding committing to working together to put at least 3.3 million EVs on the road in their states by 2025. Within that overall target, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Maryland have made commitments and proposals (here, here, here, and here) to achieve estimated state-level EV sales.

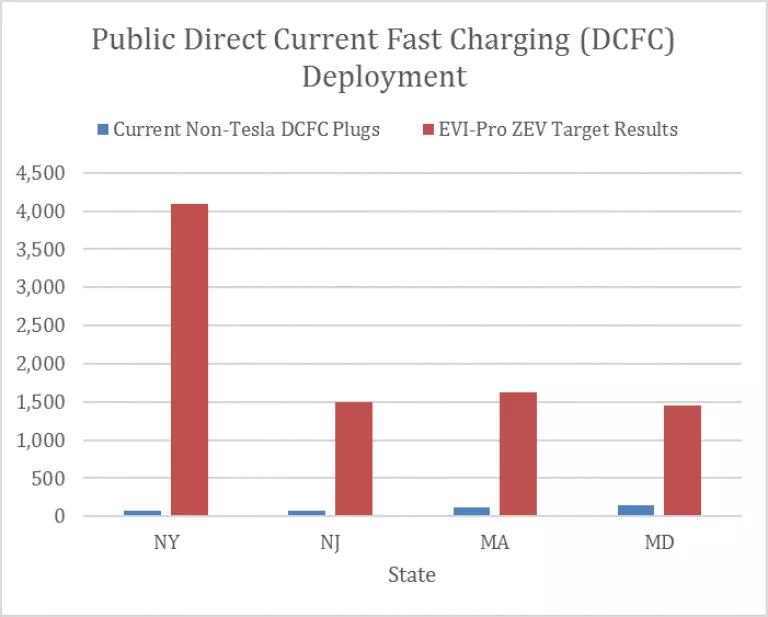

Plugging in those estimates to EVI-Pro Lite yields projected Level 2 (medium-charge) and Direct Current Fast Charging (DCFC) “plugs” or ports needed at workplace and public locations. Paired with data on existing numbers of publicly-available charging stations from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Alternative Fuels Data Center, the stark infrastructure gap becomes apparent:

(For the purposes of this blog, we assumed EVI-Pro Lite’s default shares of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles [PHEVs] and pure battery-electric vehicles [BEVs], 80 percent of EV drivers have access to charging at home, and “partial support” for PHEVs. Different inputs will yield different results.)

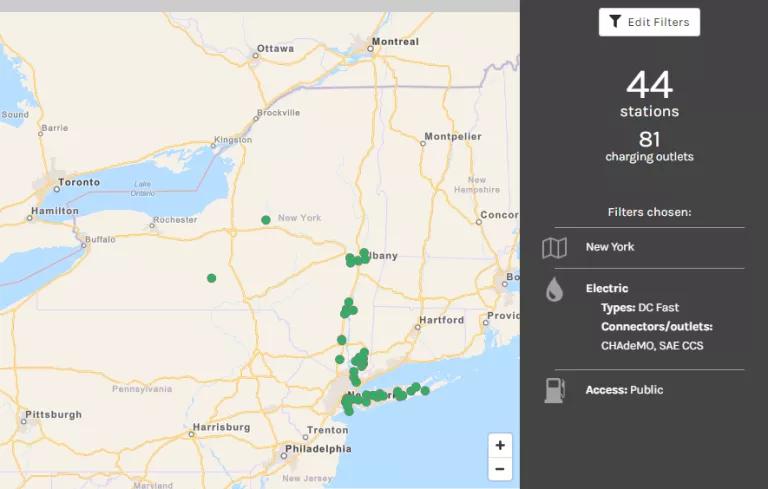

New York, the region’s leader in cumulative EV sales, has a particularly challenging ramp-up given its ZEV target of approximately 800,000 vehicles by 2025. The map below reveals 81 Direct Current Fast Charging plugs available in the Empire State today, well short of the estimated 4,087 needed to support critical charging needs for those without home charging access and to enable long-distance travel.

EVI-Pro Lite is a powerful tool that provides a snapshot of what the future of electric transportation could look like. However, modeling transportation electrification is complex, and the model does not:

- Estimate charging station needs at residences, including multi-unit dwellings, an essential market segment for charging (instead, the model uses estimated home charging availability as an input);

- Estimate charging infrastructure needs for medium-duty, heavy-duty, off-road, and other transportation modes that are already being electrified; or

- Specify where, when, or how charging stations should be deployed to satisfy model inputs.

Moreover, encouraging the growth of a robust EV market depends on more than “steel in the ground,” as a new NESCAUM (Northeast States for Coordinated Air Use Management) Northeast Corridor report suggests. Charging stations, particularly those deployed through utility customer-funded programs, should be open and easily accessible to all drivers, include clear signage and pricing information, save drivers money on fuel relative to what they’d pay for gasoline, be reliable and well-maintained, and provide opportunities for “smart” charging that encourages driver to power up when electricity demand is low.

State public utilities commissions and legislatures in the region have begun reviewing – and in some cases, already approved – measures that would enable utilities to partner with third-party service providers to develop charging networks needed to meet state goals. They must take bold action, like the Statewide EV Portfolio proposal before the Maryland Public Service Commission or House Bill 1446 in Pennsylvania, to ensure that utility customers, the grid, and the environment all benefit.

Transportation electrification is a fundamental strategy for slashing emissions from the nation’s most polluting sector. If state utility regulators and policymakers don’t act decisively to overcome barriers to widespread EV adoption, we risk leaving billions of dollars in climate, public health, fuel savings, and other benefits on the table. They must continue to lead the Northeast on clean transportation.