Down with TPP

From fracking to tainted fish, how the Trans-Pacific Partnership could affect the West.

Here’s something for conspiracy theorists: In order to gain access to a certain document, members of Congress must descend to the basement of the Capitol, hand over their cell phones and other electronic devices, and enter a secured, soundproof room. Then they can’t speak to the public about what they glean from their visit.

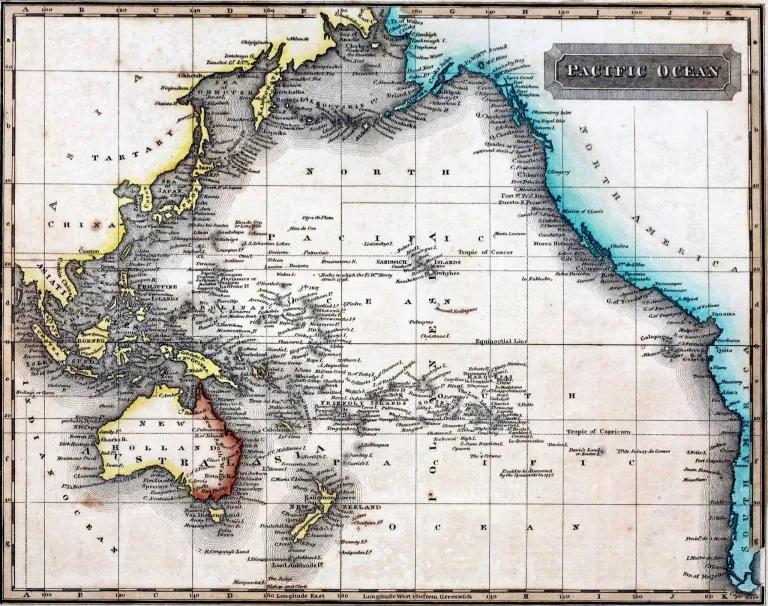

What’s so hush-hush? A draft of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), an enormous international trade agreement that 12 nations, including the United States, Japan, and Australia, have been hashing out in secret for the last half-decade. It’s a big deal: The dozen national economies make up nearly 40 percent of global GDP.

The agreement may be shrouded in mystery, but in recent weeks President Obama and some Democratic members of Congress have been publicly sparring over it—trading barbs during press conferences, on national television, and elsewhere. Critics contend the TPP would allow multinational companies to weaken environmental and labor rules here at home; the administration maintains the partnership is good for the American people and economy.

On Thursday the Senate voted to start debate on giving the president “fast-track” authority to negotiate the deal—a move that would limit Congress to voting yes or no once the nations finalize the pact (no messy fights over amendments!). Next, the battle will move to the House.

Despite the cloak of secrecy around the TPP, some draft sections have leaked, sparking concerns among green groups about everything from increased fracking to tainted seafood. “We do not believe that the rules in the TPP will be strong enough nor enforced enough to be able to lift up environmental standards outside the United States,” says Ilana Solomon, director of the Sierra Club’s responsible trade program. “At the same time, rules in the agreement could severely threaten environmental and climate policy in the States and abroad.”

On that note, here are five ways the TPP could affect the West.

Frack Attack

Many conservationists are concerned that the TPP could spur more fracking. To understand why that is, bear with me for a quick (and appalling) explanation.

The greatest tool that the TPP gives foreign corporations is a provision “buried in the fine print of the closely guarded draft,” as Senator Elizabeth Warren puts it. This is the “investor state dispute settlement” (ISDS), which grants multinationals the power to sue any government that interferes with their business. Yep, if some pesky regulation in a TPP country is hurting a corporation’s bottom line, it can sue for “millions to billions of dollars,” says Jake Schmidt, director of NRDC’s international program (disclosure). This has happened in other agreements with similar language, Schmidt says. He points out that nearly 500 ISDS cases have been brought, including a Swedish company that sued Germany because it decided to phase out nuclear power after Japan’s Fukushima disaster, and a Delaware-based oil and gas company, Lone Pine Resources, which is suing the Canadian government under NAFTA for more than $250 million because Quebec placed a moratorium on fracking.

Speaking of fracking, “The TPP would expand the export of fossil fuels and pave the way to more fracking, and therefore more emissions,” says Solomon. “It’s a major deal because Japan is one of the countries in TPP and happens to be the biggest importer of natural gas.”

To export natural gas to another country, the U.S. Department of Energy must first assess whether sending the fuel overseas is consistent with the public interest. The Energy Department, however, loses its authority to regulate exports to countries with which the United States has a trade agreement. The TPP would force it to automatically give those exports the green light. You can see where this is going. Countries that sign onto the TPP, whether the original 12 or those that join later (as China is expected to), will be able to import gas from here, then have the power to sue over any future fracking moratoria or bans around the West. (Existing anti-fracking measures, like those in communities in Colorado, California, New Mexico, and Texas, wouldn’t be affected, says Schmidt.)

Similarly, the trade deal could spur more coal-mining in the West. While U.S. consumption of the dirty fuel has been on the decline, TPP countries, including Japan, Malaysia, and Vietnam, are relying more and more on coal to keep the lights on.

Air and Water Woes

With increased fossil-fuel development comes more water and air pollution. Fracking, for instance, has been shown to contaminate local aquifers and drinking water. Adding insult to injury, considering the four-year drought gripping the West, the drilling method is also a water-intensive process. Fracking sullies the air, too; one of the by-products released, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, has been linked to cancer and respiratory ailments. Coal production comes with its own set of toxic consequences, including degraded waterways, habitat fragmentation, and health risks like pulmonary disease. And, of course, whatever fossil fuels we pull out of the ground will contribute to global carbon emissions (and that ginormous climate change problem whose effects we’re already feeling).

Fill ’er Up

The TPP's environmental effects would extend beyond wells and mines. Once fossil fuels are out of the ground, they’re on the move across the country and then around the world. As recent experience has shown, there’s no guarantee of safe transport either by pipeline or train.

By the time the fuels wind up in export terminals, extensive damage to the coastal environment has already been done. Constructing such terminals requires dredging sensitive estuaries to make room for massive tankers, and, of course, facilitates the burning of the fossil fuels being transported. Opposition has blocked some proposed facilities and delayed approval of others, such as an LNG terminal near Astoria, Oregon, for several years (the Energy Department gave it the OK last year). “Oregon has a number of proposed LNG terminals,” says Solomon, and the TPP could remove roadblocks to their construction.

Fishy Business

Americans love fish. Each year we eat nearly 5 billion pounds of seafood, or about 15.8 pounds of fish and shellfish per person. Most of that—up to 90 percent—is imported, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Of course, we aren’t the only ones with a penchant for tilapia and tuna. To meet demand, the global fishing industry is dramatically depleting stocks all over the world, while fish farms pollute waterways.

The (leaked) environment chapter of the TPP attempts, but ultimately fails, to address overfishing. It has language about prohibiting shark-finning, preventing illegally caught fish from entering international trade, and having regional fisheries managers institute best practices. Sounds good, right? Wait. “The right words are going to be in the chapter,” says Solomon, “but it won’t have any teeth.” That’s because the pact doesn’t require countries to abide by these provisions. “The only thing legally binding is ‘must’ or ‘shall,’ ” says Schmidt, “and what we’ve seen is a lot of ‘strive’ and ‘endeavor.’ I’m not sure how you’d penalize a country for not ‘striving’ or ‘endeavoring.’ ”

So the fish we import could still be illegally caught. And what’s more, the United States wouldn’t be able to ban imports of products not up to our safety standards. Shrimp aquaculture in Vietnam and Malaysia, for instance, uses pesticides and antibiotics that are forbidden in the States. “The TPP will bring a tidal wave of dangerous fish imports that will swamp the border inspectors who cannot keep up with the tainted aquaculture imports today,” said Wenonah Hauter, executive director of Food & Water Watch, in a press release.

Dirty Laundry

China has long been known as the world leader in cheap apparel manufacturing, but Vietnam is now billing itself as the best cheaper option. If the TPP comes to pass, tariffs on clothing between the United States and Vietnam will drop to zero, from 17.2 percent. With its use of excessive amounts of water, energy, and harmful chemicals, the textile industry makes the clothes we wear dirty—even if we never see the pollution. China, which produces more than 50 percent of the world’s fabric, is trying to clean up its act. But green groups are increasingly concerned about clothing made in Vietnam, which already dumps huge amounts of untreated sewage into its waterways. “Vietnam is in the Mekong Delta, in this pristine place,” says Schmidt. “Expanding the apparel industry could seriously draw down water resources and contaminate enormous quantities of water.”

* * *

While the TPP, which negotiators hope to finalize by the end of the year, is the most immediate concern, the proposed Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), a trade deal between the United States and European Union, is also worrying environmentalists. Supporters of these massive agreements often dismiss concerns that they will diminish environmental standards and other regulations at home. After all, they say, under any of the existing free trade agreements, the United States has never lost a legal case against it.

But that’s no guarantee of future success, says Schmidt. “It’s true the United States has not lost,” he says. “It’s also true that the United States is not immune to loss. Great laws and great lawyers do lose sometimes.”

This article was originally published on onEarth, which is no longer in publication. onEarth was founded in 1979 as the Amicus Journal, an independent magazine of thought and opinion on the environment. All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of NRDC. This article is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the article was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the article cannot be edited (beyond simple things such grammar); you can’t resell the article in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select articles individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our articles.

How to Become a Community Scientist

Water Pollution: Everything You Need to Know

As Trump Moves to Expand Offshore Drilling, He Proposes Shrinking Safety Protections. What Could Go Wrong?