A Horny Issue

To try and curb demand for black-market rhino horn, a bioengineering startup is making 3-D substitutes.

If you can’t beat ’em, flood the market with fakes. That’s the approach a Seattle bioengineering startup is taking to try to stem the illegal trafficking of rhino horns.

The company, Pembient, is creating synthetic 3-D printed horns in the lab. Tomorrow it will present its latest horn prototype—one-quarter the size of the real thing—at a demo day open to the public at IndieBio in San Francisco. Pembient’s aim is to produce something biologically similar to the real thing, then sell it at a tenth of the price; authentic rhino horn can reportedly go for $60,000 per kilogram on the black market. Ground-up horn has long been mixed with herbs to treat infections and reduce fever in traditional Chinese medicine. The big driver of late is a penchant for the stuff as a status symbol among Vietnam’s nouveau riche, along with its supposed abilities to cure hangovers and treat cancer (no studies have proven any of these pharmacological claims).

The company eventually plans to create synthetic versions of other highly prized, highly problematic products, including tiger bones, elephant tusks, and shark fins.

“Our goal is to end poaching,” says Pembient CEO Matthew Markus, who cofounded the company with biochemist George Bonaci in January with funding from IndieBio. “Why not just jump into the future and remove these animals entirely from the supply chain?”

It’s a bold, lofty concept—and one that conservation groups aren’t sold on. They’re concerned that rather than stem poaching, a synthetic product could whip up new demand. In a joint letter last month, the International Rhino Foundation and Save the Rhino laid out the reasons they believe the manufacture and sale of synthetic horn could “expand the market for such products, complicate law enforcement, and lead to more rhino killings.”

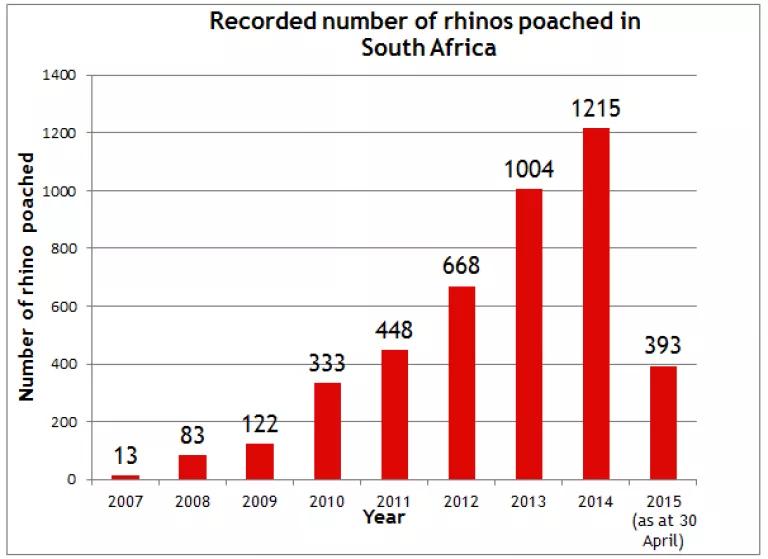

Despite the skepticism, the idea is getting attention because rhinos are in such dire straits. Despite efforts to curb consumer demand, strengthen laws against trafficking and poaching, and bolster on-the-ground protective forces, rhino poaching has been on the rise since 2008. It’s now at an all-time high: In South Africa, a record 393 animals were slaughtered for their horns in the first four months of 2015—an 18 percent increase over the same period last year. Roughly 29,000 of these odd-toed ungulates remain in the wild, down from 500,000 at the start of the 20th century, and the vast majority of the animals live in South Africa, according to the nonprofit Save the Rhino.

Markus believes faux horns could curb the relentless rise of poaching. “We think traditions are important. We think animals are precious,” he says. “We’re trying to bioengineer harmony between those things.”

Here’s how it works. Rhino horns are largely made up of keratin—a protein that’s also the main ingredient in your fingernails and hair and in animal hooves. Pembient combined keratin with other trace elements found in a natural horn, like calcium, then used that mixture as the “ink” to print the horn in 3-D. Spectrographic analyses showed it matched the real thing, says Markus. For its latest prototypes, Pembient is now incorporating rhino genetic material. After obtaining a damaged rhino horn from a museum, the company extracted its DNA, amplified it, and added it to the mix. They may also, says Markus, mark their products with a DNA watermark—a hidden short stretch of DNA with a sequence that will identify it as manmade.

The technology may very well pan out, says Sonja Boy, a scientist at the Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University in South Africa. Boy recently discovered that rhino horns are solid structures, not filled with hollow spaces, as has long been thought. (She undertook the study to help develop surgical guidelines for veterinarians with Saving the Survivors, a group that treats rhinos like this one, named Hope, with poaching injuries. “Sometimes these poachers only cut into the superficial facial tissue,” says Boy. “But sometimes they are even more barbaric than normal and crush their instruments right into the underlying nose and deeper.”) She says that while the horn’s structure is very complex, it’s still easier to reproduce than if it were comprised of hollow tubules.

Even so, she questions whether faux horn will entice consumers. “I believe they will not fall for something synthetic,” says Boy. “Poaching for ‘the real thing’ will continue.”

Pembient believes there is a market for its product. In a survey the company conducted with 480 people in Vietnam who use rhino horn for medicinal purposes, 41 percent said they'd use synthetic horn (15 percent said they'd use water buffalo, the most common current replacement).

Pembient is also banking on the purity of the ersatz horn being a selling point. “There are so many contaminants, pesticides, fallout from Fukishima,” says Markus. “Rhino horn in the lab is as pure as that of a rhino of 2,000 years ago.”

Even if fakes sell, there’s still a potentially huge economic pitfall, says Enrico Di Minin, an expert on the economic benefits of biodiversity conservation at the University of Helsinki. He says he hasn’t seen any evidence that funds from 3-D horn sales would be reinvested into helping rhinos in the wild. “If we want to be conserving species in the natural environment,” Di Minin says, “the money generated from whatever business-related activity should maximize rhino conservation.” Otherwise, poaching will continue. “We need more rangers, more boots on the ground to improve protection to a level that will actually undermine illegal activities," he says. "And that’s very expensive.”

That’s precisely the problem, says Markus—the approaches so far haven’t made a significant dent in poaching. “It’s not like the traditional methods haven’t been tried, and the combined response has been an increase in [the number of rhinos killed] over the last five years,” he says. “That’s a failure, by any metrics.”

Pembient’s product could hit the market as early as this fall. In the meantime, other efforts to curb poaching and trafficking and bolster rhino numbers continue. That includes a project to move 100 rhinos by 2016 from high-poaching zones in South Africa to Botswana, which has the lowest levels of poaching on the continent, attributed to the country’s zero tolerance when it comes to illegal hunters. (Its Botswana Defense Force enforces a “shoot to kill” policy.)

Rhinos Without Borders successfully transported the first 10 rhinos to their new home last month. That endeavor also required technology, but the old-fashioned kind: trucks and airplanes.

This article was originally published on onEarth, which is no longer in publication. onEarth was founded in 1979 as the Amicus Journal, an independent magazine of thought and opinion on the environment. All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of NRDC. This article is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the article was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the article cannot be edited (beyond simple things such grammar); you can’t resell the article in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select articles individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our articles.

When Customers and Investors Demand Corporate Sustainability

Protecting Biodiversity Means Saving the Bogs (and Peatlands, Swamps, Marshes, Fens…)

How to Make an Effective Public Comment