The Sequencer is Mightier Than the Sword

A new study of ivory DNA could help send elephant poachers on the run.

The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service brought a ton of ivory to Times Square this morning—and crushed it into tiny pieces. The service hopes to send a message to poachers and traders that the United States is committed to protecting elephants and curtailing the ivory business.

Conservationists are still waiting for the Obama administration to finalize its ban on ivory sales, and New York City is one of the country’s biggest hubs for the illegal ivory trade. Still, the sight of all those tusks in the middle of Manhattan makes you wonder, Why shouldn’t we be able to put a stop to elephant poaching at its source?

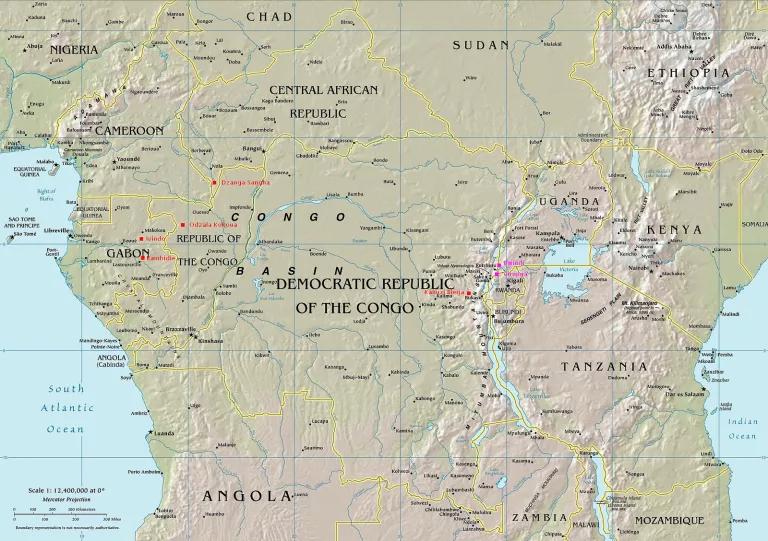

It turns out that’s a tall order. Elephants range more than one million square miles of Africa. Policing an area that size is nearly impossible. To put it in perspective, New York City employs approximately 73 police officers per square mile. Deploying a similar law-enforcement presence across the elephants’ African range would require every single person in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the continent’s third-most populous country, to quit their jobs and become anti-poaching police—and we’d still be short more than a million cops.

Since the effort will always be underfunded and understaffed, the key to stopping poaching is to deploy the few rangers we can afford as efficiently as possible. A study released yesterday in the journal Science is a step toward that goal. University of Washington biologist and elephant ivory expert Samuel Wasser analyzed 28 major ivory seizures between 1996 and 2014. Comparing the confiscated ivory’s DNA with DNA collected from elephant dung of known origin, Wasser found that poachers have narrowed their hunting grounds substantially over the past decade.

Almost all the forest elephant ivory in Wasser’s sample came from a single protected ecosystem that spans northeastern Gabon, northwestern Democratic Republic of Congo, southeastern Cameroon, and the southwestern corner of the Central African Republic. (That’s a lot of countries, I know, but it’s a reasonably small area.) The ivory from elephants living on savannahs also came from a limited area, located mostly in Tanzania but spilling into northern Mozambique.

This research is a gift to the anti-poaching effort. In the short term, it provides a ready-made strategy: Work with those countries mentioned and focus law enforcement in two manageable parts of Africa. Poachers will eventually respond by moving to less policed areas, but having to constantly pick up and move will exact a toll on the elephant hunters. Poaching requires the right infrastructure and conditions, such as roads to get the poachers in and the ivory out, access to trade routes, and porous borders. Small-time poachers will always be difficult to stop, but keeping the business small would represent a major victory.

And we could use a major victory right now, because progress seems to have stalled. According to United Nations data, the illegal wildlife trade is now worth $20 billion per year, making it one of the world’s largest forms of organized crime. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora announced that elephant poaching rates remained unchanged between 2013 and 2014, at a level that exceeds the species’ natural growth rate. Some estimates put elephant-poaching deaths at 96 each day, putting the animal on a steady decline into extinction. Rebel groups and poachers attack, torture, and murder anti-poaching police with alarming regularity. One watchdog group claims that at least two park rangers are killed every week.

A single article in a Western academic journal isn’t going to change those facts overnight, but it is an extremely useful starting point. I, for one, would be delighted if a guy with some test tubes in a laboratory could thwart thousands of bad men with guns.

This article was originally published on onEarth, which is no longer in publication. onEarth was founded in 1979 as the Amicus Journal, an independent magazine of thought and opinion on the environment. All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of NRDC. This article is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the article was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the article cannot be edited (beyond simple things such grammar); you can’t resell the article in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select articles individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our articles.

When Customers and Investors Demand Corporate Sustainability

Protecting Biodiversity Means Saving the Bogs (and Peatlands, Swamps, Marshes, Fens…)

How to Make an Effective Public Comment